Pat yourself on the back – you’ve made it to the last ACS post. Today we’re going to discuss “guideline directed medical therapy” (GDMT) post ACS. But you’re not just going to memorize what your patients should be on – your going to understand why we give these meds (well, hopefully). Also, some recs may differ slightly depending on whether or not your patient came in with NSTE-ACS or STE-ACS. Without further ado, let’s get into it:

Beta Blockers

Your heart has receptors on its surface known as beta-1 adrenergic receptors. These receptors are predominantly found in the heart. Beta-1 receptors are activated by the sympathetic nervous system – specifically activated by the binding of adrenaline (epinephrine) and noradrenaline (norepinephrine). Epinephrine and norepinephrine are hormones naturally created by our adrenal glands.

When stimulated, these beta-1 receptors increase cardiac output, increase heart rate (chronotropy), increase atrial contractility (inotropy), increases conduction and automaticity within the AV node.

Even though stimulation of the beta-1 receptor is needed sometimes (like when you see a bear in the woods), keep in mind that our ACS patients just underwent ischemia and even necrosis to their cardiac tissue. Some of these patients may even now have poor cardiac squeeze, or systolic heart failure, with new onset reduced EFs. If you remember from our ACS pathophys talk, these patients are particularly susceptible to developing ventricular dysrhythmias.

By blocking the beta-1 receptor with beta blockers (e.g. metoprolol, carvedilol, etc), we are allowing the heart to chill out and slow down. This will help decrease myocardial ischemia and reinfarction and will also help with cardiac remodeling.

Beta blockers also reduce the frequency of ventricular dysrhythmias in these patients and have been shown to improve long term survival in ACS patients.

Beta blockers should be ideally started within the first 24 hours of presentation and continued at discharge. This is consistent for both NSTE-ACS and STE-ACS. All of them recommend the use of BB without contraindications irregardless of EF and really should be the backbone of therapy post ACS to help with cardiac remodeling, decreasing ventricular dysrhythmias, and improve long term survival.

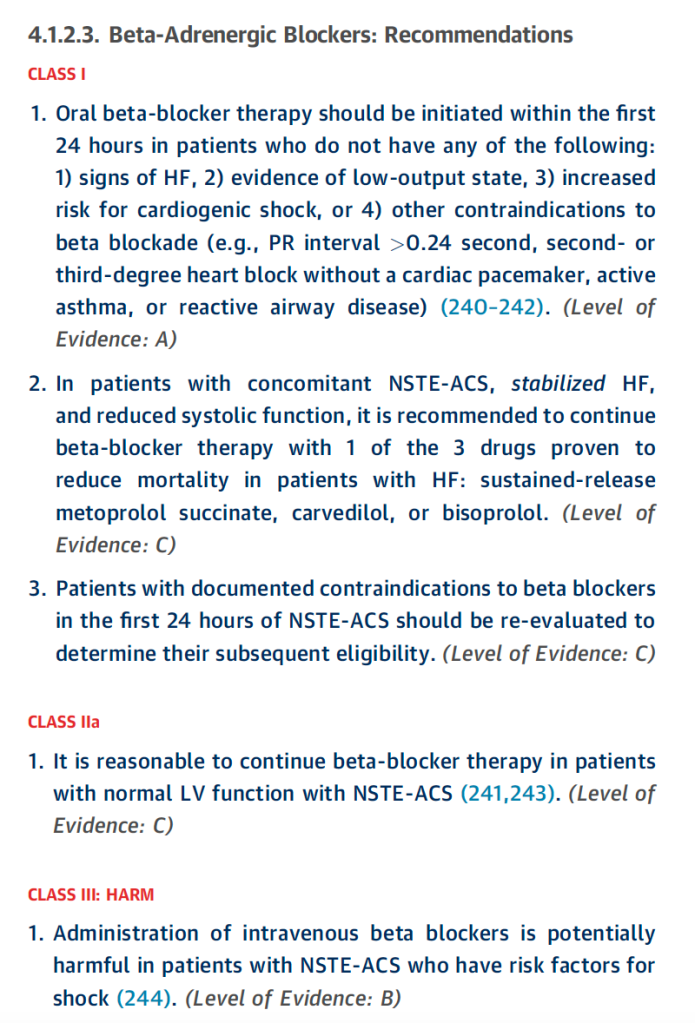

NSTE-ACS Guidelines

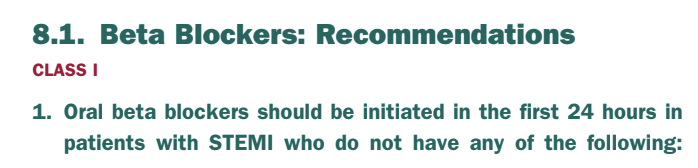

STE-ACS Guidelines

So to summarize: in NSTE-ACS, it’s a 1a indication to give to patients with reduced EF – however it’s a IIa indication to give them to patients irregardless of EF status.

In STE-ACS, all patients should get them.

So TLDR – pretty much all patients should get a beta blocker post ACS unless there’s a good reason not to.

Update: more and more data is challenging this belief, and suggests that in patients with normal EFs, beta blockers may not do anything. Keep an eyeball out for the next set of guidelines as I believe ESC has already implemented these changes.

Statins

Let’s think about how this all started – our lipid plaque filled with LDL and other inflammatory molecules.

Statins (e.g. atorvastatin, rosuvastatin, etc) work to decrease cholesterol formation by inhibiting the key enzyme in cholesterol synthesis – known as HMG-CoA reductase. Inhibiting this enzyme will decrease the synthesis of cholesterol and LDL and therefore help prevent these lipid plaques from forming in the future.

Unless contraindicated, all of your ACS patients should not only be on statins, but should be on a high intensity statin. Statins are categorized based on their ability to decrease LDL. There are low intensity statins that on average, decrease LDL by <30%; the moderate intensity statins lower LDL ~30-49%, and the high intensity statins lower LDL by at least 50% on average.

Now listen, I’m not that big on students memorizing doses of every drug ever, because in reality, most of this will come with clinical experience. However, I do think you should know the high intensity statins and their doses: rosuvastatin 20-40mg, and atorvastatin 40-80mg. Note that we used to do simvastatin 80 mg as well, until they found out that this dose had more side effects and the FDA recommended against.

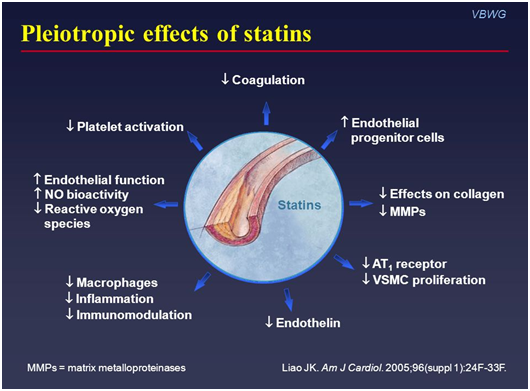

Even though it takes statins a few weeks to start decreasing LDL levels in the blood, statins have really cool pleiotropic effects. Pleiotropy means that a drug has actions other than those for which the agent was specifically developed.

Statins have been found to decrease inflammation, decrease platelet activation, decrease coagulation, increase nitric oxide concentrations, etc. All things that can be very helpful for our coronary arteries after an ACS event.

Despite the fact that statins may take a while to have LDL effects, their early benefit post ACS has been proven with data. So please – get those statins on board. 🙏🙏🙏🙏

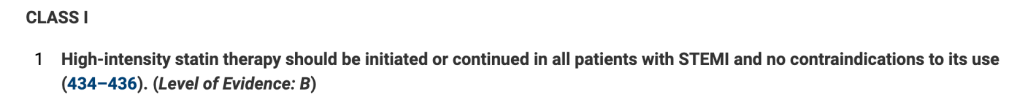

These high intensity statins (much like the beta blockers) are really important backbone of therapy post ACS no matter if your patient had an NSTEMI or a NSTE-ACS.

TLDR: everyone who can tolerate them should get a high-intensity status post ACS, irregardless if they had a NSTE-ACS or a STE-ACS.

ACE-Is/ARBs

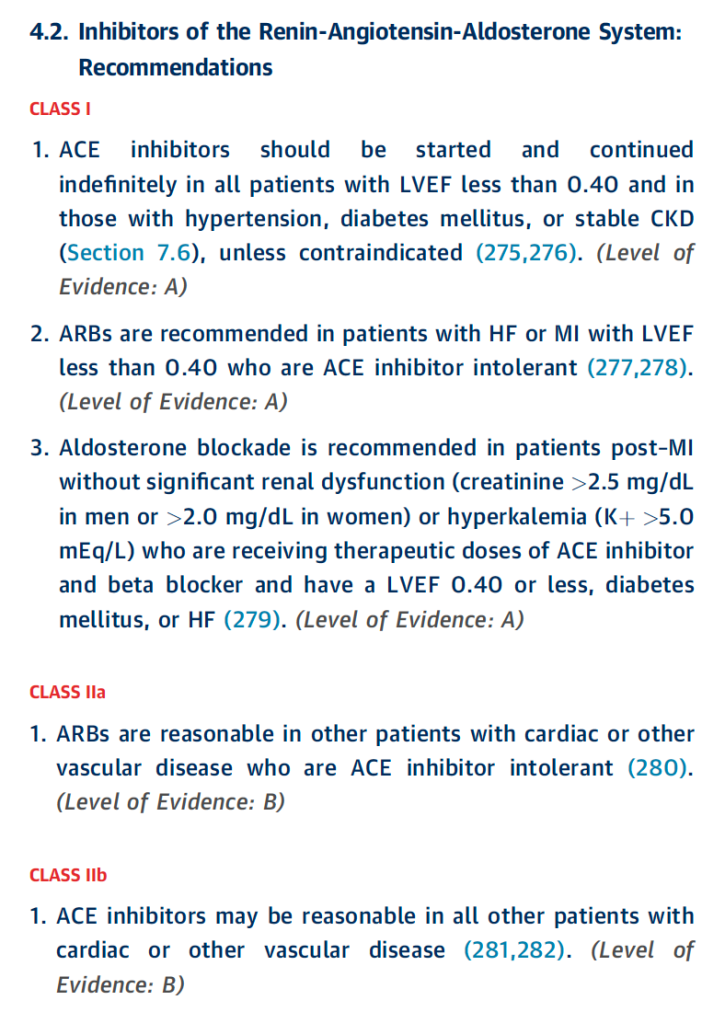

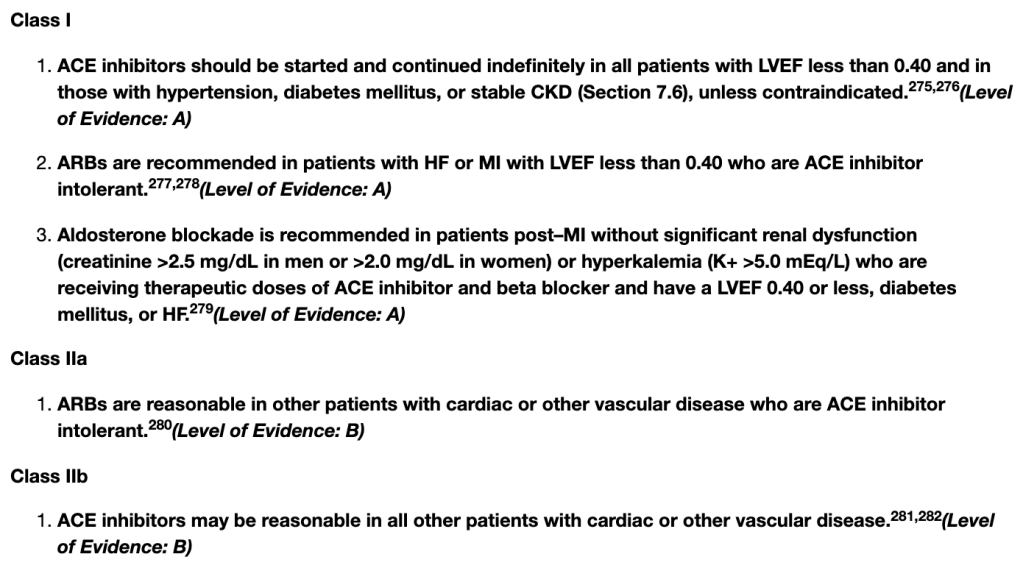

We can definitely have a post in and of itself on ACE-Is/ARBs in the future, but get your patients on an ACE-I (or ARB if ACE-I intolerant) before discharge. These meds work by inhibiting the renin-angiotensin aldosterone system. They also help to slow ventricular remodeling as well. Remember in our first ACS post when we said that patients with new systolic (HFrEF/low ejection fraction) heart failure patients may recover some of their ejection fraction within 40 days? Well, ACE-Is (and ARBs) are here to help with preventing that remodeling to allow for these patients’ hearts to return (hopefully) to their pre-ACS EFs. Besides that, both ACE-Is and ARBs work on reducing afterload, which will then reduce work on the heart (mostly the left ventricle) and make it easier to pump blood out to the body. This is great because these patients have these stunned, possibly newly poor squeezing hearts that need all the help they can get to decrease their workload in pumping blood out to the rest of the body.

NSTE-ACS Guidelines

STE-ACS Guidelines

To summarize the above, the most compelling indications to start an ACE-I/ARB post ACS is those with an LVEF <40%, HTM, DM, or stable CKD. However, both guidelines also have a IIa indication that put them on irregardless of the above. So realistically, most patients post ACS should get an ACEi/ARB if they can tolerate it.

Wait, what about sacubitril/valsartan?!

So we just talked about how ACE-Is and ARBs help with cardiac remodeling but what about our latest contenter, sacubitril valsartan (brand name Entresto). We had some good data for sacubitril/valsartan in some other disease states (like HFrEF – we will discuss later) and so there was some hypotheses that if ACEI-s and ARBs helped post ACS then maybe sacubitril/valsartan would work too, right?

Hence this first 2020 study that found that early initiation of sacubitril/valsartan may have benefit with cardiac remodeling post STEMIs versus ramipril. This was a fairly small trial, with an n=~200 patients.

The most painful line of this trial (in hindsight, which is of course 20/20) is: “An ongoing larger randomized trial with longer follow (Prospective ARNI vs ACE Inhibitor Trial to DetermIne Superiority in Reducing Heart Failure Events After MI; PARADISE-MI) is eagerly awaited to confirm our results”.

The results of the PARADISE-MI this May unfortunately did not confirm this study and found no difference in the primary outcome of CV death, first HF hospitalization, of outpatient HF for sacubitril/valsartan versus ramipril. The jury is currently out on sacubitril/valsartan immediately post ACS so for now, go for the ACE-I or ARB.

Aldosterone Antagonists

These are actually also addressed in the above sections on ACE-I/ARB inhibition since it all boils down to blocking that RAAS system. They are another backbone of therapy as they are indicated for any post ACS patient with an LVEF <40%, diabetes, or heart failure. You will often see them used after we are sure the patient can tolerate their ACE-I or ARB, since aldosterone antagonists also can cause hyperkalemia just like the ACE-Is/ARBs do. They don’t have that sweeping “but yeah, everyone can get it ” recommendation, so mainly they go on for our EF <40%, diabetes or HF patients.

Nitrates

Every patient who goes home post ACS should get their lil nitroglycerin tabs to use in case of chest pain and be well counseled on when to seek ED care for potentially another ACS event.

Back in my day, it was that patients could take 2-3 tablets under their tongue before calling 911. However, the new rule of thumb is that if the pain is not relieved OR gets worse 3-5 min after 1 dose, you should seek emergency services.

DAPT, DAPT, DAPT!

After learning all about the pathophys of a type I myocardial infarction, it should be of no surprise that (especially after stenting) DAPT with a P2Y12 inhibitor and ASA is a must to prevent in-stent thrombosis. After all, you have this new foreign object that helping keep your coronary artery open, but what good is it if it clots off? Cue stent thrombosis, recurrent MI, medical emergency.

If you remember from our talks about stents, the risk of stent re-thrombosis decreases over time as the stent begins to endothelialize and tissue builds up to cover it. So it should make sense that the sooner after your patient received a stent, the higher the risk of stent thrombosis. Which is why the guidelines doesn’t say do DAPT forever – and cut if off at 12 mo, after which you switch to ASA monotherapy indefinitely.

The thrombotic risk after CABG differs from what you’d expect after a stent because CABG is using grafts from the patient’s own body (aka not foreign material) so the thrombotic risk is somewhat less and although we tend to do DAPT (specifically with clopidogrel) post CABG, if your patient had a high bleed risk, they could get away with aspirin monotherapy right off the bat.

Side note: the guidelines for ACS haven’t been updated since 2013 and 2014. Yep, you heard me. I was literally a teeny booper back then. So with that being said, a lot of data has come out in the interim about shortening DAPT duration (and I mean A LOT – i’m looking at you GLASSY, GLOBAL LEADERS, HOST-EXAM, MASTER-DAPT, SMART-CHOICE, STOPDAPT2, TICO, and TWILIGHT).

The other issue we run into is what do we do with patients who came in (prior to their ACS event) with an indication for anticoagulation at baseline – so for example, our patients that came in with history of a recent DVT, Afib, etc? Technically they’d, in theory, be indicated for triple therapy – anticoagulation + ASA + a P2Y12 inhibitor right? YEESH. That comes with a high risk of bleeding.

Luckily for us, there have been trials that already looked at some practices for us (e.g. WOEST, AUGUSTUS, etc). For patients who receive a stent and have a pre-existing indication for anticoagulation, we usually drop the ASA, and keep the anticoagulation + a P2Y12 inhibitor (usually clopidogrel given it’s lower risk of bleeding).

However, if your patient got a CABG, usually we are OK with anticoagulation + ASA and to drop the P2Y12 inhibitor given that ASA alone is usually “good enough” to protect the graft. After all, the graft isn’t a foreign material like a stent is, so it has a decreased thrombotic risk vs a stent.

Depending on the patient’s individual thrombotic risk, we might opt to do triple therapy for a very very short duration of time (~1 week or so but you might see some MDs pushing it depending on thrombotic vs bleeding risk factors) and then drop one of the agents as above.

Calcium Channel Blockers

Ehhhh, I don’t see calcium channel blockers too often post ACS. Let’s check out what the guidelines say first.

2014 NSTE-ACS AHA/ACC Guidelines

So let’s summarize here. In NSTE-ACS (NSTEMIs and UA), if your patient can’t tolerate a BB, you should consider giving them a non-DHP CCB (but not if they have a low EF, or systolic HF because then that’s actually contraindicated). You can also use non-DHPs chronically if you have recurrent ischemia as a third line option after BB and nitrates to help with angina.

The only time I really see CCBs used is when long acting calcium channel blockers are used for patients who have coronary artery spasm. These patients can have ACS events that are not due to plaque rupture but actually due to lack of blood flow to the myocardium due to the coronary arteries spasming. CCB can help with that spasming.

Looking at the 2013 ACCF/AHA STE-ACS guidelines, they ring somewhat similar:

Again, nothing really first line as far as looking at reinfarction or infarct size but they can help with angina/ischemia, BP management, help slow heart rates if your patient is intolerant to BB. Again do not use non-DHP CCBs (e.g. verapamil, diltiazem), in patients with low EFs. Non-DHP CCBS reduce inotropy (squeeze) which is the last thing we want in our HFrEFers.

Also, literally never use IR nifedipine like, ever. Kidding.

But also kinda not really.

But in all seriousness, don’t use IR nifedipine during ACS since it abruptly drops pressure and your body will compensate in that drop in BP (remember BP= CO x SVR) by increasing CO by, you guessed it, increasing heart rate (CO=HRxSV), thus increasing necrosis and ischemia of that clogged coronary artery because you are increasing the demand of oxygen that heart needs as it speeds up its heart rate.

And that, my friends, is ACS in a nutshell. I could go on all day, but let’s move on to another topic next. Next stop on this blog is to talk about one of my favorite topics, heart failure.

Happy holidays, guys.