*Now ✨updated✨ with the latest 2022 ACC/AHA/HFSA Guidelines*

Welcome back to the blog. Today we’re going to be discussing how we treat chronic diastolic heart failure, also known as heart failure with preserved ejection fraction or HFpEF.

What is HFpEF? A quick review.

If you haven’t read my post “Heart Failure – Why it’s an ☂️ Term” I would recommend doing that quickly now. I go into the important differences between HFrEF and HFpEF and why having a normal ejection fraction can still mean you have heart failure.

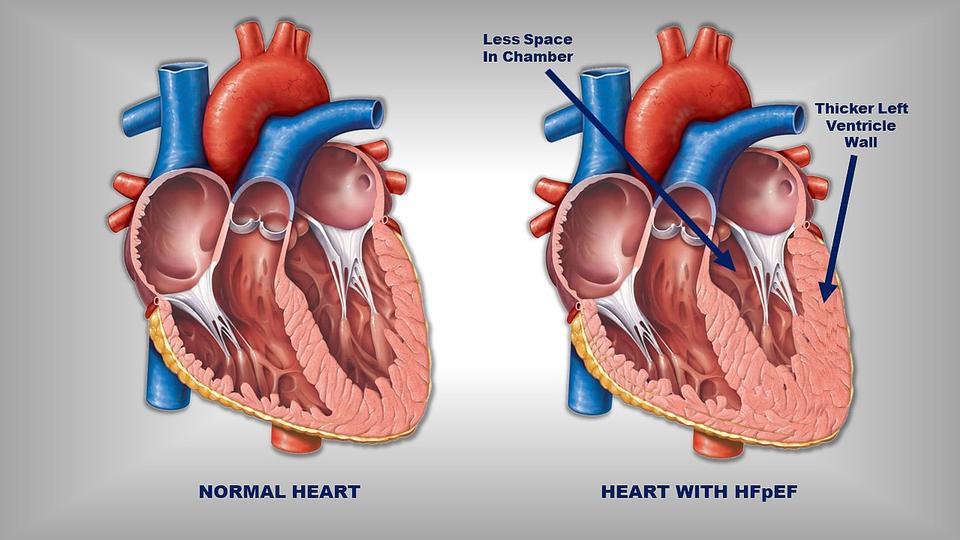

In HFpEF, patients end up with a hypertrophied, super thick, stiff, left ventricular wall.

I always go back to the analogy that your heart is a muscle just like every other muscle in your body.

If I went to the gym (I don’t) and lifted weights, what would happen to my biceps over time? They would grow, right?

Your heart is no different. If chronically faced against abnormally high pressures, your left ventricle will grow and hypertrophy and that left ventricular space where blood usually fills will start to shrink.

This is why, despite having perfectly good contracting power, your heart is unable to get enough blood pumped out to the body, and why diastolic heart failure is indeed, heart failure.

Treatment of HFpEF

Oh HFpEF. The forlorn stepchild of heart failure. For so long, we knew of nothing that could really help these patients.

Afterall, the structural differences, causes, and pathophysiology that leads to HFpEF is so unlike HFrEF.

For the longest time, all we had to “treat” these HFpEF patients was basically to manage any underlying causes. In fact, that’s what our guidelines still mostly say.

Take a second to Google the “2017 ACC/AHA/HFSA Focused Update of the 2013 ACCF/AHA Guideline for the Management of Heart Failure: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines and the Heart Failure Society of America” (that’s a mouthful). These were the old guidelines.

If you go to section 7.3 (Pharmacological Treatment for HFpEF), you’ll see a couple of weak and/or vague recommendations.

For example:

Manage blood pressure.

Use diuretics PRN if volume overloaded.

If they have CAD, consider revascularization.

Manage Afib, if they have it.

It’s not for a lack of trying. All the HFrEF GDMT has, as some point or another, been tested in these HFpEF patients.

But we just don’t see that benefit in HFpEF patients that we do in HFrEF patients for those drugs.

Then came….spironolactone.

Hold onto your seats because, not gonna lie, this story is low-key pretty dramatic in the world of medicine.

If you remember, systolic heart failure patients (HFrEF) saw great benefit in mortality and hospitalizations in the 1999 RALES trial, which we’ve discussed before. Well, in 2014, spironolactone was tested in HFpEF patients.

The TOPCAT trial.

Very very controversial. I love teaching learners about this trial. Why? Let’s jump into it.

The TOPCAT trial investigated the following: among patients with HFpEF – does spironolactone reduce cardiovascular mortality, aborted cardiac arrest or heart failure hospitalizations versus placebo?

Like many other beefy CARDS trials, the TOPCAT trial was a multicenter, randomized, placebo-controlled trial that looked at 233 sites in 6 countries. They enrolled patients in the Americas (North and South) as well as Eastern Europe.

The trial was intention to treat which means if you were assigned at the beginning of the trial to take spironolactone (aka be in the treatment arm), no matter what you did (if you missed doses, deviated from protocol etc) you would still be included and analyzed in the spironolactone arm.

The TOPCAT trial look at these HFpEF patients, with their comorbidities mostly controlled (e.g. only included patients with SBP <140 or <160 if on 3+ antihypertensives). After a mean follow up of 3.3 years, the results were released.

And

….they were kinda disappointing. Yet another “failure” in the realm of HFpEF treatment.

With an n of 3,445 patients, they failed to meet significance in their primary outcome of CV mortality, aborted cardiac arrest, or heart failure hospitalization with a P value of 0.14.

When looking at these components alone, there was some benefit seen in HF hospitalizations (12.0% versus 14.2%), with a P=0.04, and a number needed to treat of 45.

Hey, it’s not great, but it’s something, right?

This led to the class IIb, LOE B-R recommendation in the HFpEF guidelines that:

In appropriately selected patients with HFpEF (with EF ≥45%, elevated BNP levels or HF admission within 1 year, estimated glomerular filtration rate >30 mL/min, creatinine <2.5 mg/dL, potassium <5.0 mEq/L), aldosterone receptor antagonists might be considered to decrease hospitalizations.

Simple enough right? But here is where things start to get *spicy*.

When looking at the data, the investigators noticed that there seemed to be a pretty unusual discrepancy when dividing up the data based on region. In other words, data in one region looked a lot more promising than data from another region. Keep in mind that this was an international trial afterall.

The data looked so weird that it actually prompted a post-hoc analysis to be done (https://www.jacc.org/doi/10.1016/j.jacc.2017.04.025?_ga=2.43497765.1677304012.1642099914-706451054.1631903970).

And the results were jaw-dropping (imo).

The post-hoc analysis broke up patients based on region. One group looked at the Americas (US, Canada, Brazil, Argentina) and the other group looked at Eastern Europe (Russia and Georgia).

They found a couple of bizarre things.

- The rates of hyperkalemia and increased SCr (things that you might expect from spironolactone use) were much higher in the Americans group and

- When looking specifically at the Americas group alone, the composite endpoint was significantly reduced with a primary outcome composite P value of 0.026, and we also saw significant reductions in CV mortality (p=0.027), hospitalization (p=0.042), and all-cause mortality (p=0.08).

What

the

heck

is

going

on.

There was further digging into the bloodwork of these subjects during the study period and they found that a whopping 30% of patients from Russia/George did not have spironolactone or its metabolites detected in their blood.

Wow.

In other words, all this data suggests that patients in Russia and Georgia may have significantly deviated from protocol, and – we might not have seen enough the benefit of spironolactone because these patients weren’t taking it.

And because such a large proportion of the patients in the TOPCAT trial were from Russia and George, when we put all these patients together, we failed to see that composite reduction in the primary endpoint.

But the question remains – what do we do with this for the guidelines? Is it ethical to recommend spironolactone in the guidelines based on this extreme data digging? Likely not. Recommending this in the guidelines would skew the new level of what is “acceptable” data to become “good data”.

And so, we are doing a new study to confirm these ambiguities. The SPIRIT-HF trial (Clinical Trials NCT04727073)

Unfortunately, it’s probably going to be a few years until we get that data, but until then, we wait.

But in the meantime, if you ask this lowly PharmD, I push to get these HFpEF patients on spironolactone knowing all the nuances of this data.

Next came the ARNIs – sacubitril/valsartan.

Sacubitril/valsartan was the first ever FDA approved drug for HFpEF. !!!!

Wahoo! We finally did it! We found a great drug that even got FDA approval. Entresto for everyone! Right?

Well…..in my opinion, the data is a little iffy. I was actually quite surprised when I heard it got FDA approval based on the data. The said data is based on the PARAGON-HF trial.

The 2019 PARAGON-HF trial looked at patients with HFpEF, NYHA class II-IV symptoms, and EF ≥45%, elevated natriuretic peptide levels, and evidence of structural heart disease. The real question was – does sacubitril/valsartan lead to reduced rates of total hospitalizations for HF and death from CV causes versus valsartan alone?

With an n=4,822 and a median follow up of 35 months, what did the primary outcome show?

The composite of HF hospitalizations and CV mortality had a relative risk of 0.87 with a 95% CI of 0.75-1.01. In other words….it failed to meet statistical significance between groups. When breaking down the composite endpoint, neither the HF hospitalizations endpoint or CV mortality hit statistical significance either. There was also significant difference in secondary endpoints of KCCQ clinical summary score or death from any cause.

You might be thinking (and I hope you are) – I thought you said sacubitril/valsartan became FDA approved for HFpEF based on this trial?

Yeah…it did. And the justification for this was based on one of the many subgroup analyses that was done in this trial. Among looking at other things like age, sex, race, region, eGFR, etc, they also looked at ejection fraction. They found that patients with an EF ≤ 57% just hit statistically significance with a relative risk of 0.78 and a 95% CI of 0.64-0.95. Those with an EF >57%, on the other hand, did not, with a RR of 1.00, and a 95% CI of 0.81-1.23.

This proportion of patients with an EF ≤ 57% – a patient population I would call HFmrEF (heart failure with mildly reduced ejection fraction) is what lead to the FDA approval of sacubitril/valsartan in HFpEF.

My thoughts on this are mixed. Imo, the data is overall weak. Afterall, remember when we talked about the ISIS-2 trial which looked at aspirin use in MI (see discussion here: ). They did a subgroup analysis based on astrological sign and found that Geminis and Libras actually had an adverse effect to aspirin. 🤷🤷🤷 In other words – fish enough for something, and you will find something that happens to be stat significant.

On the other hand, making this drug “FDA approved” for HFpEF may help out with patient access in getting the medication and we’re still talking about a disease state where we don’t have that many options.

Again, this is the important part about looking at the data for yourself and going based off of the latest news in CARDS. If I didn’t look at the data for myself, I would probably say “ooooo, sacubitril/valsartan is FDA approved for HFpEF it must be so great, we should definitely add that first line”. Always allow yourself to formulate your own opinion of the data that you can back up, even if it differs from mine.

Lastly, the latest kids on the block were the SGLT-2 inhibitors.

Just like how they were studied in HFrEF, empagliflozin and dapagliflozin were recently also studied in patients with diastolic heart failure as well.

The two trials looking at SGLT-2s in HFpEF were the EMPEROR-PRESERVED trial for empagliflozin and the PRESERVED-HF for dapagliflozin and gained these drugs FDA approval for the treatment of HFpEF.

The EMPEROR-PRESERVED trial looked at n=5988 patients with class II-IV HFpEF (defined as EF >40%) to receive empagliflozin versus placebo. Primary outcome looked at a composite of cardiovascular death or hospitalization for heart failure. With a median follow up of 26.2 months, they saw a significant reduction in events in the empagliflozin group, mainly driven by a reduction in hospitalizations. This effect was seen irregardless of diabetes status at baseline.

The PRESERVED-HF (dapagliflozin vs placebo) trial was a smaller study and look at n=324 patients with HFpEF, w/ or w/o T2DM, NYHA class II-IV who had elevated natriuretic peptides, requirement for loop diuretics, and either have had a HF hospitalization or needed IV diuretics within 12 mo. This trial looked at a somewhat softer endpoint – symptoms – and the primary outcome was KCCQ-CS at 12 weeks. Dapagliflozin improved the KCCQ-CS at 12 weeks with a P=0.001 due to improvements in both symptoms and physical limitations – and was seen irrespective of diabetes status.

The 2022 ACC/AHA HFSA Guidelines

In April of 2022, the ACC/AHA/HFSA dropped their new HF guidelines! HFpEF has come a long way since 2017.

SGLT2is, not surprisingly, earned the highest class recommendation of the GDMT meds (a class 2a) given the robust RCT trials showing benefit in these patients.

Next you’ll see the ARNIs, MRAs, and ARBs put together, with a 2b recommendation.

My personal opinion would be to do spironolactone first, then trial an ARNI – but this is all based on the data.

And that’s HFpEF in a nutshell!