Today we’re going to focus all of our time looking at the basics of two drug classes, look at their mechanisms of actions, effects, side effects – all that good stuff. Today’s “classic” is on Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitors (ACE-Is) and Angiotensin II Receptor Blockers (ARBs).

Important Pre-Readings:

In order the really get the most out of this lecture, you should first read these. Seriously, you’ll understand things a lot better. If you don’t know what I mean by glomerulus versus nephron versus bowman’s capsule or preload vs afterload, click the below ⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️⬇️

The Renin Angiotensin Aldosterone System

The History of ACE

Believe it or not, it wasn’t really that long ago that none of this stuff (the ACE-Is and ARBs) existed. It wasn’t until 1956 when a scientist named Leonard Skeggs (et al) discovered angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in plasma.

Around that same time, over in southwestern Brazil, employees who worked in banana plantations were collapsing after being bitten by pit vipers.

Scientists at the time were investigating what the heck in that pit viper venom led to such instant hypotension.

In 1965, they found that the heckin’ thing in the venom of pit vipers was bradykinin-potentiating factor (BPF).

Source: Wikipedia

But what is bradykinin?

Bradykinin is a naturally occurring peptide that our body produces to promote inflammation. It does this by causing the arterioles in the body to dilate by stimulating the release of things like prostacyclin and nitric oxide. Keep in mind even though trigger words like inflammation in 2022 are thought to be bad, inflammation is actually a very important part of the healing process, triggering the promotion of white blood cells and red blood cells to migrate to a specific area in the endothelium.

After the original discovery of ACE, scientists next investigated where the conversion of angiotensin I to angiotensin II (by ACE) happened in the body. Originally it was thought that this conversion happened in plasma, but it quickly was found that plasma ACE is too slow to account for the conversion.

After more investigation, they found that the rapid conversion of angiotensin I -> angiotensin II happened through passage through the pulmonary circulation, hence why we frequently associate the ACE enzyme with the lungs.

Source: UF Health

Around this time, they also discovered that bradykinin disappears by a single pass through the pulmonary system.

So to summarize, angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) not only converts angiotensin I to angiotensin II but also is responsible for inactivating circulating bradykinin.

ACE = ⬆️ angiotensin II and ⬇️ bradykinin.

As we reviewed in the RAAS pre-reading, angiotensin II is a potent vasoconstricting agent, and so it would make sense to block either the

1) formation of angiotensin II or the

2) binding of angiotensin II to its receptor

to help with patients with hypertension control their blood pressure.

In other words, if we can make chemical structures that target this system, we can help treat hypertension in our patients.

After the structure of ACE was figured out in the 70s, the first ever FDA approved ACE-inhibitor agent – captopril was FDA approved in 1981, with enalapril coming out 2 years later. Since then, multiple ACE-Is have been introduced since.

Mechanism of Action: The Difference between ACE-Is and ARBs

Though they both work to prevent the effects of angiotensin II, the differences in MOA are 🔑key🔑 to understand the nuances in side effects between the two classes of drugs.

A quick refresh regarding the RAAS system.

When the RAAS is activated, angiotensin I (which is fairly biologically inactive) is converted into angiotensin II by angiotensin converting enzyme (ACE) in the lungs.

Binding of angiotensin II to the angiotensin II receptor induces systemic vasoconstriction and increases blood pressure by increasing systemic vascular resistance (because remember that BP = CO x SVR).

Angiotensin Receptor Blockers, aka ARBs, are angiotensin II receptor blockers (aka angiotensin II receptor antagonists). All ARBs end in sartan. For example, valsartan, losartan, olmesartan, telmisartan.

ARBs = “sartan”

ACE-Is = “pril”

Angiotensin Converting Enzyme Inhibitor (aka ACE-Is), work by blocking the action of the ACE enzyme. These drugs end in pril. For example, lisinopril, enalapril, captopril.

Because ARBs do not work on the ACE enzyme (remember that they block the angiotensin II receptor) when patients are on an ARB, their ACE enzyme will still be active.

What effects would this have on their bradykinin levels in the body?

Because we’re not messing with their ACE enzyme, angiotensin I will still be converted to angiotensin II but angiotensin II will not be able to bind to the receptor to have its effect. However, you also won’t be messing with the levels of circulating bradykinin in the body. Since the ACE enzyme is responsible for depleting bradykinin levels, and you aren’t touching the ACE enzyme with ARBs, you will still get that expected breakdown of bradykinin within the body.

Contrast this to the ACE-Is: by working directly to inhibit the ACE enzyme, ACE-Is block that ACE enzyme. Which means that not only can this enzyme not work to produce angiotensin II from angiotensin I, but the ACE enzyme also cannot do its job to breakdown circulating bradykinin. Because of this, patients on an ACE-I will have higher circulating levels of bradykinin.

This central differences in MOA will be v important to understand the different side effects of ACE-I versus ARBs.

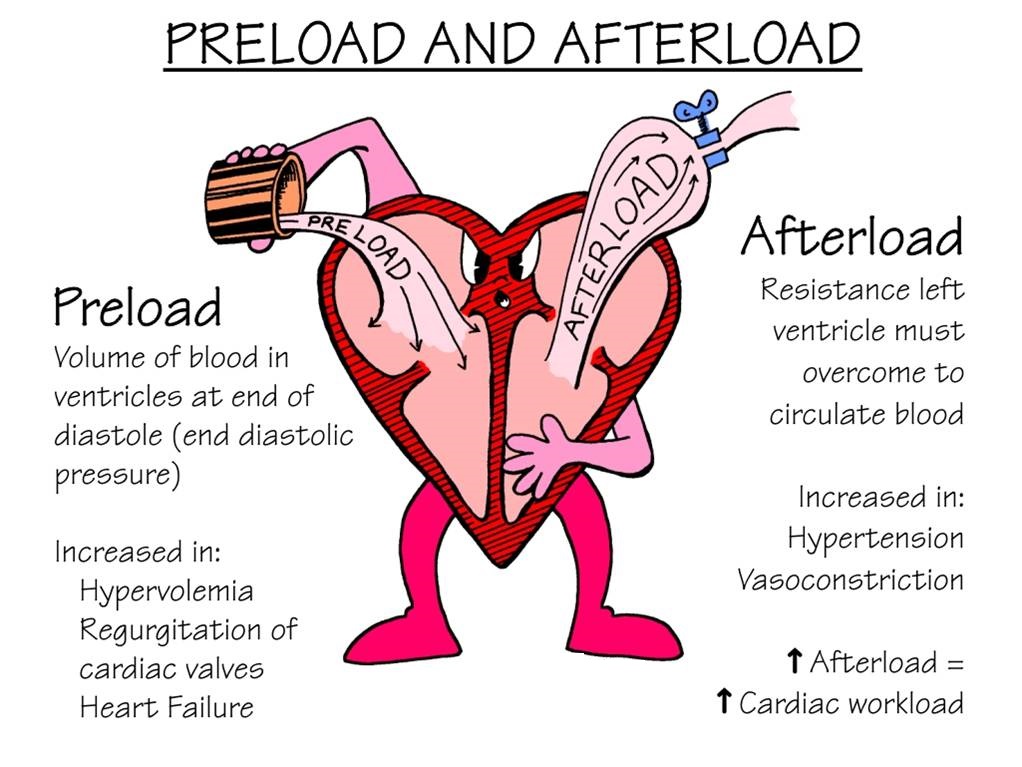

Effects on Preload and Afterload

ACE-Is and ARBs prevent angiotensin II from doing its thang (through different mechanisms) on all the main vasculature, so ACE-Is and ARBs decrease both preload and afterload by dilating both the veins and the arteries. If you don’t know what preload and afterload are, click me.

Source: FacultyofMedicine

A Rare but Serious ADR: Angioedema

What is angioedema?

Angioedema is swelling that occurs underneath the skin (in the subcutaneous or submucosal tissues) as opposed to on the skin’s surface (like you might have had if you have had hives before).

Though rare, ACE-Is can induce angioedema in patients. The thing that makes angioedema so scary/a big deal is that it tends to commonly affect the lips, tongue, face and upper airways of patients. Because of this, patients may develop airway obstruction, massive tongue swelling and even asphyxiate as a result. No bueno. Let’s not have that happen. Technically, angioedema can also happen at any time during ACE-I therapy.

So why do these drugs cause angioedema?

Though still rare, the risk of developing angioedema is much higher with the use of ACE-Is versus ARBs. Why do you think that might be?

By blocking the ACE enzyme, keep in mind that ACE-Is also increase the circulating levels of bradykinin, which is a pro-inflammatory vasoactive peptide. By increasing these levels of bradykinin, you are increasing the risk of developing angioedema. Patients undergoing ACE-I induced angioedema have been associated with having high bradykinin levels.

Another important thing to note is that the incidence of ACE-I induced angioedema is up to five times greater in patients who are of African descent, thought to be due to genetic polymorphisms that lead to lower levels of other enzymes (e.g. APP, NEP) which also are responsible for breaking down bradykinin.

What about ARBs?

The data with ARBs is a little less clear. Mechanistically, you wouldn’t expect patients on ARBs to have a higher risk of developing angioedema, since they do not interfere with bradykinin metabolism. Though earlier data suggested recurring angioedema in ACE-I patients switched to ARBs due to angioedema, more recent studies have not found that ARBs are associated with anymore angioedema than any other antihypertensive agent, like beta blockers. Overall, still something to keep on the back of your mind, but really associated with ACE-Is.

Again, friendly reminder that this is a rare side effect. We literally put a bajillion (ok maybe a lil exaggerating) patients on ACE-Is throughout the world. But something to always keep in mind as a healthcare practitioner.

Treating Hypertension: ACE-I/ARB “Compelling” Indications

If you look at the hypertension guidelines (both the 2017 ACC/AHA HTN guidelines or the 2020 ISTH HTN guidelines), you’ll see that ACE-Is or ARBs are recommended first-line (aka ahead of our other agents like thiazide diuretics and calcium channel blockers) in patients with diabetes (especially in those with proteinuria), as well as in patients with CKD (stage 3 or higher or stage 1 or 2 with albuminuria).

But what is unique about ACE-Is and ARBs in these populations? Why would we want to preferentially use them?

It all comes back to understanding the physiology and what these drugs are doing in the body.

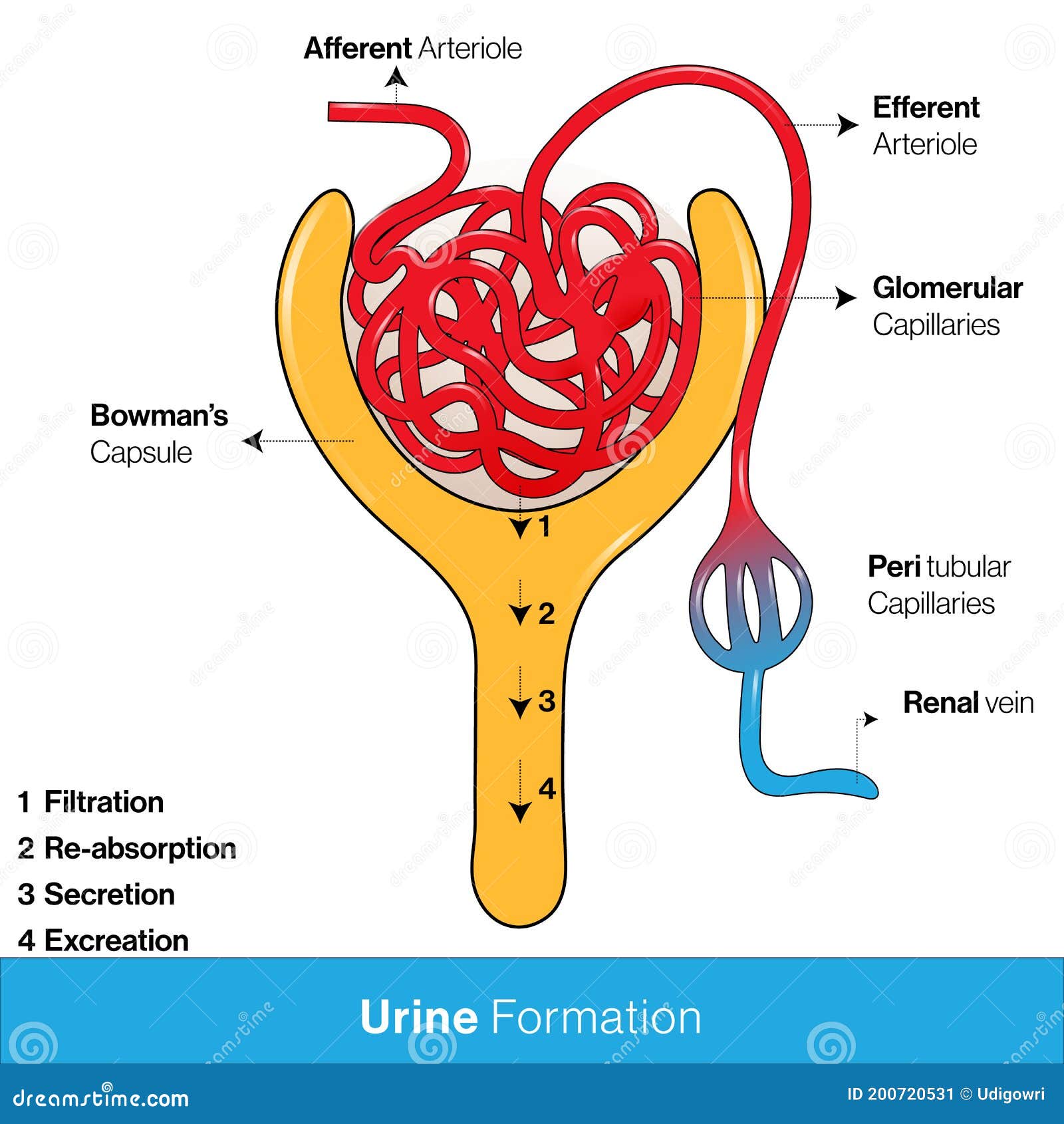

If you remember in our RAAS talk, when we went through renal blood flow, we talked about the renal corpuscle which is comprised of a knot of capillaries known as the glomerulus.

The glomerulus carries our body’s blood and is surrounded by a double-walled capsule known as the Bowman’s capsule.

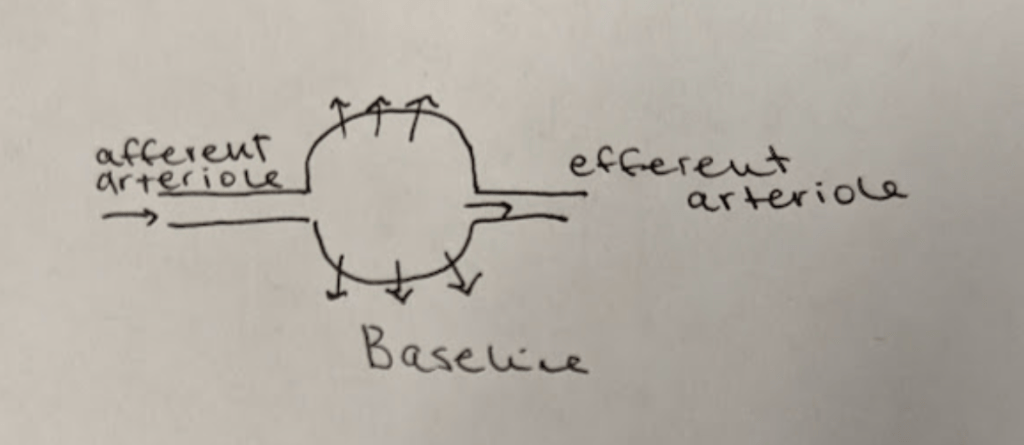

The blood enters the glomerulus through the afferent arteriole and enters the Bowman’s capsule. This is the area in the nephron where the initial filtering of urine occurs; the part that will become urine is filtered out of the blood and enters the tubules, and the rest of the filtered blood will leave the Bowman’s Capsule and leave through the efferent arteriole.

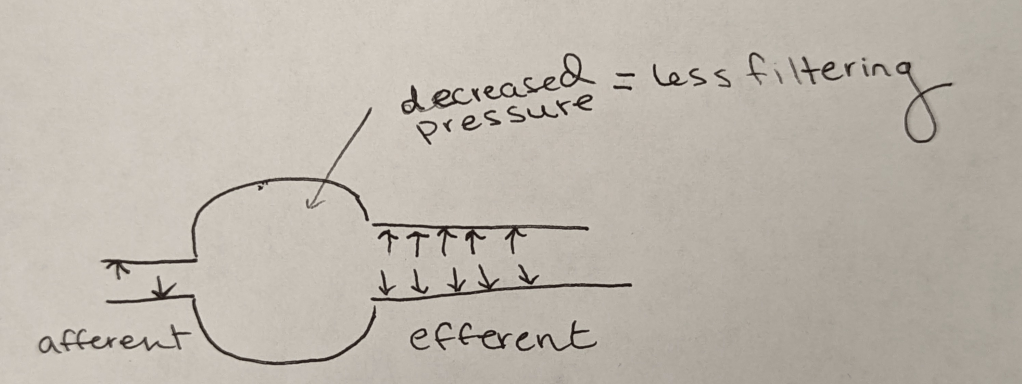

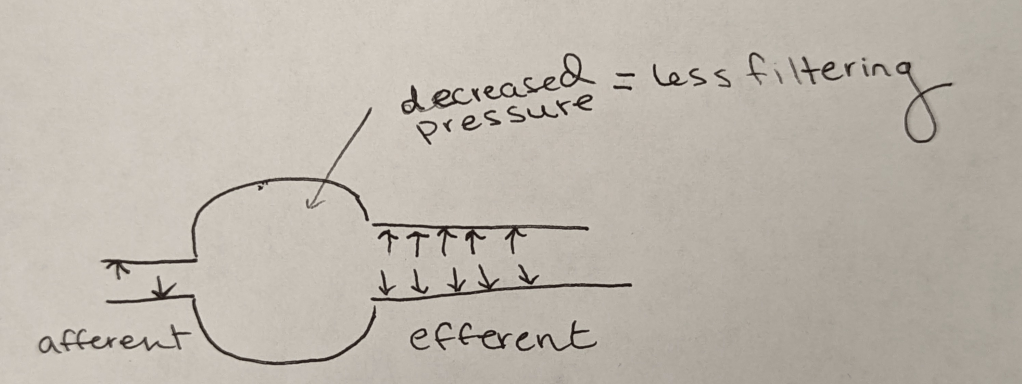

I’m a visual person, so if you’re like what the heck, I suggest re-reading the above and looking at the diagram below simultaneously.

The part that we are now going to focus on is the afferent arteriole and that efferent arteriole.

In this scenario, think e for exit – therefore the efferent arteriole is the arteriole that exits the bowman’s capsule.

It’s also important to note that the pressure within the glomerulus (aka the glomerular capillaries) is what generates and promotes the filtration of the future urine out to the tubules. This is what we call hydrostatic pressure. In other words, the higher the pressure within the glomerular capillaries, the more fluid that will be pushed out of the blood and filtered into the tubules.

ACE-Is and ARBs can work to dilate the afferent and efferent arterioles.

The important thing to note, however, is that they dilate the efferent arteriole way more than they dilate the afferent arteriole.

Efferent Vasodilation >>> Afferent

Now, I couldn’t find a photo online that really showed what I wanted to show. So get ready for some ugly homemade drawings. Sorry I’m not more artistic.

Check out that ugly photo above.

This is what your kidneys look at baseline.

To orient you, we have the afferent arteriole on the left bring blood into the glomerulus/bowman’s capsule (that circle/ball thing), where urine will be filtered out of the blood via hydrostatic pressure (hence the lil arrows filtering out).

All the remaining blood will then exit the glomerulus/bowman’s capsule via the efferent arteriole.

Like I said before, ACE-Is and ARBs work to dilate that afferent arteriole a bit, but dilate that efferent arteriole a lot more. Net result is what you see above.

Now….question.

What do you think is going to happen with that hydrostatic pressure inside of that glomerulus/bowman’s capsule as a result of this change?

Because that efferent arteriole dilates a ton, it is easier for blood to flow out into the afferent arteriole right? In other words, the pressure inside of the glomerulus/bowman’s capsule will decrease.

Because that hydrostatic pressure is decreased, you will end up with less filtering (less filtrate aka future urine) within that bowman’s capsule.

What clinical implications does this have?

In order to understand why this is important, you have to think about what a normal kidney versus damaged kidneys look like.

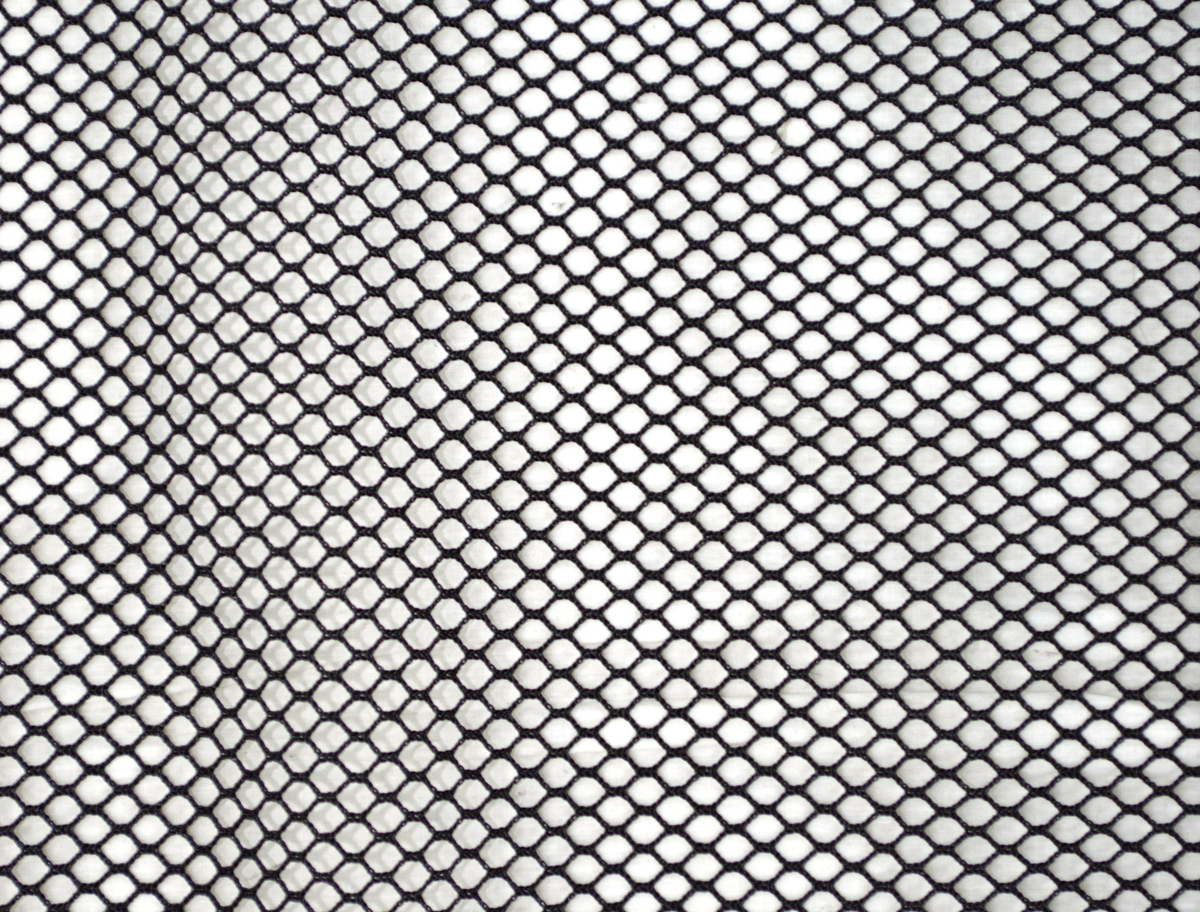

In healthy kidneys, the glomeruli are able to nicely filter blood and extra solutes out. I like to think about healthy kidneys as having a really nice, healthy, fine mesh that is able to filter out the teeny solutes and waste from our blood.

The larger stuff, like protein, is not usually present in urine in healthy individuals. However, if your kidneys become damaged as a result of diabetes, high blood pressure, etc, that fine mesh net is damaged. That fine mesh net now has bigger holes in it, holes that it’s not supposed to have. As a result, proteins start being able to leak through and become present in the urine. Not good. 😬😬😬

Let’s use chronic hypertension patients as a good example.

Your patient has high blood pressure over a long period of time, and that glomerulus is subject to higher pressures than normal. As a result, that high pressure starts pushing again that fine mesh net and starts to damage it and make holes in it. The patient will start developing CKD as a result of their chronic hypertension and as that net gets damaged, you’ll start seeing proteins like albumin spill into their urine.

Now that you have a little bit of background, we can talk about why ACE-Is and ARBs are recommended over our other first line agents in CKD and DM patients.

By dilating that efferent arteriole and decreasing that filtering pressure, ACE-Is and ARBs can work to prevent further damage to that mesh net.

They can’t really do much to reverse the damage that is already done, but by decreasing the pressure that that net has to be put under, ACE-Is/ARBs can prevent any more holes from getting bigger or new ones from forming. Which is exactly why we like to use these meds in patients with CKD and/or diabetics that have proteinuria.

Adverse Events: Increase in SCr

Because ACE-Is and ARBs work on the afferent arteriole and decrease the pressure within the glomerulus, they also decrease the amount of filtrate/filtration that occurs in the kidneys, right?

Because of this, you can expect that the ACE-Is/ARBs will increase serum creatinine in patients.

Just a reminder that creatinine is a waste product made by muscles and is normally excreted out of the body by the kidneys. We like to use the blood level of creatinine (aka serum creatinine) as a surrogate marker for kidney function.

Because everyone has different baseline SCr values (for example, a teeny old lady without any muscle mass might have a baseline SCr whereas Dwayne the Rock Johnson may have a SCr of 1), we like to use a percentage increase to determine what increase in SCr is safe when we start ACE-Is/ARBs in our patients. Afterall, if we set a concrete number instead – like an increase of 0.2 mg/dL – that wouldn’t be much for DTRJ (Dwayne the Rock Johnson) but would be an increase of 50% for our teeny old lady.

Rule of thumb: When starting ACE-I or ARB therapy, an increase in SCr of up to 30% is acceptable.

For example, if your patient’s baseline SCr is 1, and you start them on an ACE-I and their follow up BMP reveals a SCr of 1.3, don’t freak out. It’s an expected effect of the ACE-I – continue to monitor and don’t necessarily run to stop that ACE-I/ARB.

Why do we use ACE-Is/ARBs in CKD but not in AKI?

This can be a little tricky at first – we like to use ACE/ARBs to “save” the kidneys in chronic kidney disease, but we don’t want to start them in patients with acute kidney injury, or AKI.

Hopefully I can make it make sense.

During AKI, we want to avoid any extra insult from happening to the already stunned kidneys. When you’re in pre-renal AKI, your body may try to compensate for the decrease in blood flow seen at the kidneys but preferentially constricting the efferent arteriole. If you start an ACE-I or ARB, you are blocking this compensatory mechanism from happening.That decrease in GFR that ACE-Is/ARBs cause might just be enough to further tip our patients into either a worsened AKI or new onset CKD.

Btw, if you are a little uncomfortable with the term “prerenal” AKI and what that means – it means exactly what it sounds like – the issue is prerenal aka before the kidney. Prerenal AKI is when there is nothing wrong with the kidney itself, but rather a lack of blood flow (renal hypoperfusion) to the kidneys. Because those kidneys aren’t seeing good blood flow, they become damaged due to the lack of oxygen.

Other ADRs – Hyperkalemia and Cough

A very common side effect of ACE-Is and ARBs is hyperkalemia. You want to make sure to keep an eye on their BMP (both to monitor their K levels and their SCr levels).

Angiotensin II usually exerts a positive feedback loop. If you forgot what that means, positive feedback is process where the end products of a cascade cause more of that action to occur – in other words, it amplifies the process. Usually, when the RAAS system is activated, angiotensin II is made and that angiotensin II will stimulate aldosterone to be secreted in the adrenal gland.

Aldosterone causes sodium to be absorbed (aka causes sodium and water retention) and potassium to be excreted in the kidneys.

Both ACE-Is and ARBs 🚫interfere🚫 with the stimulatory effect of angiotensin II on aldosterone secretion in the adrenal gland. By inhibiting the stimulation of aldosterone, there will be less potassium excretion through the urine and as a result, patients may become hyperkalemic. This effect is commonly seen with both ACE-Is and ARBs – so you want to make sure you keep an eye on it.

Cough is another commonly seen ADR, but it is seen specifically with ACE-Is and not ARBs. This side effect, similar to angioedema, all traces back to the increased bradykinin levels we see with ACE-Is (and not ARBs). Bradykinin has been found to induce an enzyme known as COX-2 in airway smooth-muscle cells which causes increased thromboxane-B2 production and stimulates cough. The cough seen with ACE-Is is commonly described as a dry persistent cough, and can occur at any time (e..g within hours after first dose or months later). The incidence of ACE-I induced cough is more commonly seen in women than men and more in African American and Asians than others. If bothersome enough, it may prompt the switching of the ACE-I to an ARB.

An easy way to remember some of the ACE-I side effects:

A = angioedema

C = cough

E = elevated potassium and SCr

Big Contraindications

Pregnancy: Both ACE-Is and ARBs are known to cause fetal renal damage in pregnancy. Because of this, they should be avoided in pregnant patients.

Bilateral Renal Artery Stenosis: whenever you see/hear the word “stenosis”, think of a narrowing. Bilateral renal artery stenosis is when both renal arteries are narrowed. In renal artery stenosis, the afferent pressure (aka the pressure in the vessel entering the glomerulus) is reduced by the narrowed vessel. Because of this, the only way these patients can autoregulate their GFR/kidneys is through vascular changes made to the efferent arteriole. By giving these patients ACE-Is or ARBs, you are taking away their ability to autoregulate their kidneys, glomerular perfusion will fall and renal failure will occur as a result of ischemic nephropathy.

Comparing Agents: ACE-Is

As I said before, there are a lot of different ACE-Is available on the market. So what’s the differences between them? Why would I use one over the other? ACE-Is are classified into three main groups depending on their chemical structure. I’m gonna talk about the main ones that you’ll be likely to see.

- Sulfhydryl-containing ACE-Is: captopril

- Dicarboxylic-containing ACE-Is: e.g. benazepril, enalapril, lisinopril, ramipril

- Phosphorus-containing ACE-Is: fosinopril

All ACE-Is are given orally with the exception of enalaprilat. Enalaprilat was found to have a super low bioavailability (was not well absorbed into the bloodstream when taken orally) so is only given IV. Luckily they came up with enalapril, which is a prodrug of enalaprilat which much better bioavailability. Once absorbed, it is converted to enalaprilat and does its thing.

Keep in mind that prodrugs are drugs that have to be chemically activated in order to have their intended effect. In other words, they have to be converted in vivo (in the body) to another chemical compound to have its intended action.

All ACE-Is with the exception of lisinopril and captopril are prodrugs. Because prodrug activation typically primarily happens in the liver, in patients with liver dysfunction, non-prodrug ACE-Is (like lisinopril or captopril) are preferred.

All ACE-Is have similar effects on blood pressure reduction, without any clinically meaningful differences between agents (keep in mind the equivalent doses are different though). There also does not appear to be any clinical differences among the agents in their treatment of heart failure. However, generally drugs like captopril, enalapril, fosinopril, perindopril, quinapril, and ramipril are usually preferred since we know their target effective dose in heart failure patients.

Another main difference between agents is their duration of action. Some ACE-Is are short acting, while some are intermediate or long acting. The only true short-acting ACE-I is captopril. Captopril only has a duration of effect of about 6-8 hours, which is why it’s dosed multiple times a day. For this reason, you don’t commonly see it used outpatient – I mean, who the heck wants to take TID medication where there are QD options that work the same way? However, in the world of inpatient medicine, captopril is a great agent to have up our sleeves. Why?

Because it has such a short duration of action, captopril is actually what I would consider a semi-“titratable” oral agent.

No, it’s not the same as IV antihypertensive agents that have (or should have) a quick onset and offset, but it’s still great to have.

Imagine if you only had a long-acting ACE-I on formulary like lisinopril. Let’s say your patient has hard to control hypertension. You give a dose of your lisinopril and – your patient is still hypertensive. So you give another dose, and another. What’s going to happen in that patient?

Because of the long duration of action of enalapril, you can experience dose-stacking or drug accumulation – and if your patient now ends up hypotensive, you’re just going to have to support them until all that accumulated drug washes out. Blegh.

Captopril on the other hand washes out quickly, relatively speaking. If you give a patient a dose and they don’t respond how you like, you can give a higher dose and not worry (or worry less) about dose stacking. Because of this, you can more quickly titrate their dose to figure out what dose is good for them – and then eventually convert them to a longer-acting agent later on or prior to discharge. Going along with this train of thought, captopril is also great for really tenuous patients, who tend to get hyper or hypotensive and fluctuate easily.

The intermediate acting ACE-Is include enalapril and quinapril – these drugs stick around for about 12 hours. This is why enalapril, for example, can be given BID, or twice daily.

The long acting ACE-Is include drugs like lisinopril and ramipril. These drugs stick around for ~24 hours, hence their QD dosing.

So why would I use enalapril over lisinopril or visa versa? We know these drugs have similar effects on things like BP, so why would I prefer one agent over another?

It all boils down to being patient-specific. If your patient’s BP is well controlled throughout the day on a once daily agent – like lisinopril – I would keep it on.

But if your patient tends to get BP fluctuations – for example, if they tend to get more hypertensive prior to bed as that lisinopril is starting to wear off, maybe an intermediate-acting, BID medication like enalapril would be better for that patient.

Note: ACE-I agents have been shown to differ in their ability to inhibit tissue ACE. Drugs like enalapril, captopril and lisinopril have less affinity than other agents. However, currently no data supports superiority of agents based on this difference.

Comparing Agents: ARBs

Although they all block the AT1 receptor, ARB agents differ a little bit in pharmacokinetics based on their molecular structure. They do have some nuances between agents and we’re going to get into some of the major ones.

Hepatic Impairment: No dose adjustments are needed for irbesartan in patients with hepatic impairment. For those with moderate hepatic impairment, dose adjustments are needed for candesartan, losartan and telmisartan. There’s no data in patients that have severe hepatic impairment for azilsartan, candesartan, losartan and valsartan.

Blood Pressure Reduction: there are some differences in BP reduction between agents but all have similar safety and tolerability. There’s not a ton of good data directly comparing agents, but it suggests that olmesartan is more effective at reducing BP than losartan, valsartan and irbesartan. Losartan, valsartan, candesartan and telmisartan have also been shown to reduce LV mass in hypertensive patients,

Dosing Frequency: unlike the ACE-Is, there’s no short acting ARB, relatively speaking. The majority of ARBs are dosed once daily for hypertension, with candesartan being dosed QD or BID.

And that’s ACE-I and ARBs, in a nutshell. At the end of the day, if you can understand these drugs – their mechanisms of action, how they work – you will be more likely to remember their side effects. And remember – practice makes perfect. I still don’t know the dosing of some of these less common ACE-Is or ARBs – the more you deal with agents in practice, the more familiar they will become. This is why I’m not huge on harping on individual dosing – I’d rather you understand the concepts of the drug – the rest can be quickly looked up.

Greetings! Very helpful advice in this particular post! It’s the little changes which will make the most important changes. Many thanks for sharing!

LikeLike