Today we’re going to discuss a mainstay of treatments for patients with atrial fibrillation – anticoagulation.

If you haven’t done so already, I’d really recommend taking a quick look at my Atrial Fibrillation: An Overview post, or else you might find yourself a little lost, since I’m not taking time here to review basic definitions and describe afib here today. Sry not sry.

Anyway, let’s jump into it.

Why do we anti-coagulate patients with atrial fibrillation?

Patients with atrial fibrillation have an irregular rhythm in the atria (upper chambers) of their hearts. Because of this, instead of getting nice, coordinated, smooth contractions of the atria…the atria just….kinda sit there and quiver.

Because of this, the blood in the atria – that would normally be ejected out briskly, undergoes some stasis, or pooling.

In other words – it sits around more than it should.

Anytime blood undergoes stasis, or a period of inactivity/loss of movement, it’s going to want to clot.

Usually this stagnant blood thing isn’t a problem in healthy patients, but in patients with atrial fibrillation, that quivering of the atria is going to set up the perfect conditions to make that blood want to clot up.

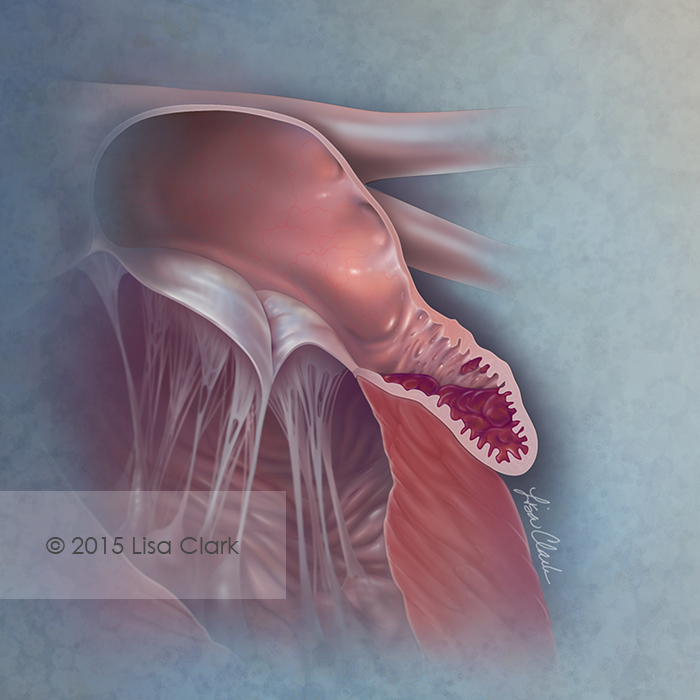

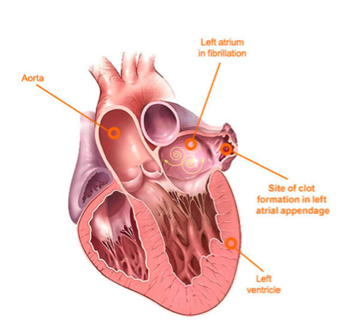

Unfortunately to make matters worse – our hearts have something called a left atrial appendage or LAA.

The left atrial appendage is this growth, almost like a little pocket, that branches out of your left atria.

Unfortunately for us, the presence of this teeny little nook makes the blood that enters it go even slower. In fact, the majority of clots that are formed in patients with atrial fibrillation originate in this left atrial appendage.

Ok, ok Cait- so we know that atrial fibrillation patients are at risk for forming clots in their left atrium right?

But what are the clinical implications of this?

If you go back and remember the post on Coronary Anatomy-An Overview, you’ll remember that the flow of blood in the area of our left atrium goes as follows:

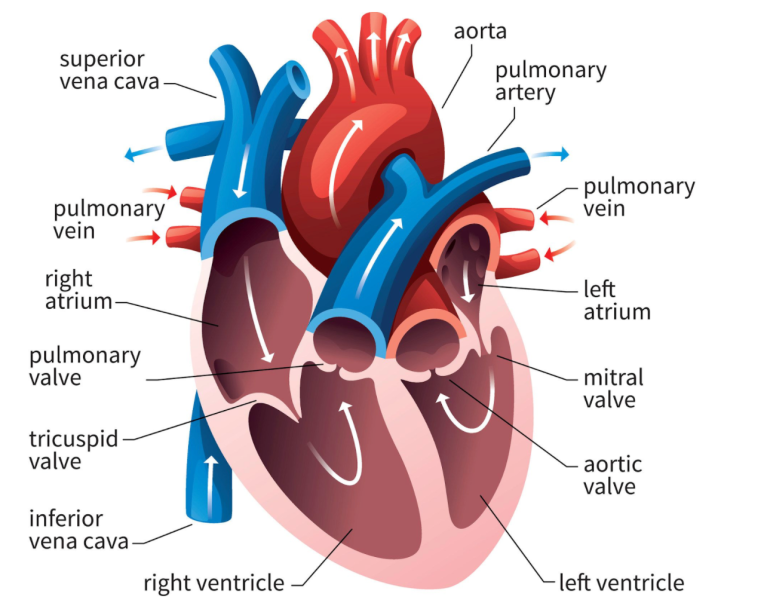

Blood leaves our left atrium through our mitral valve, and enters the left ventricle. The left ventricle will then contract and propel that blood out the aorta.

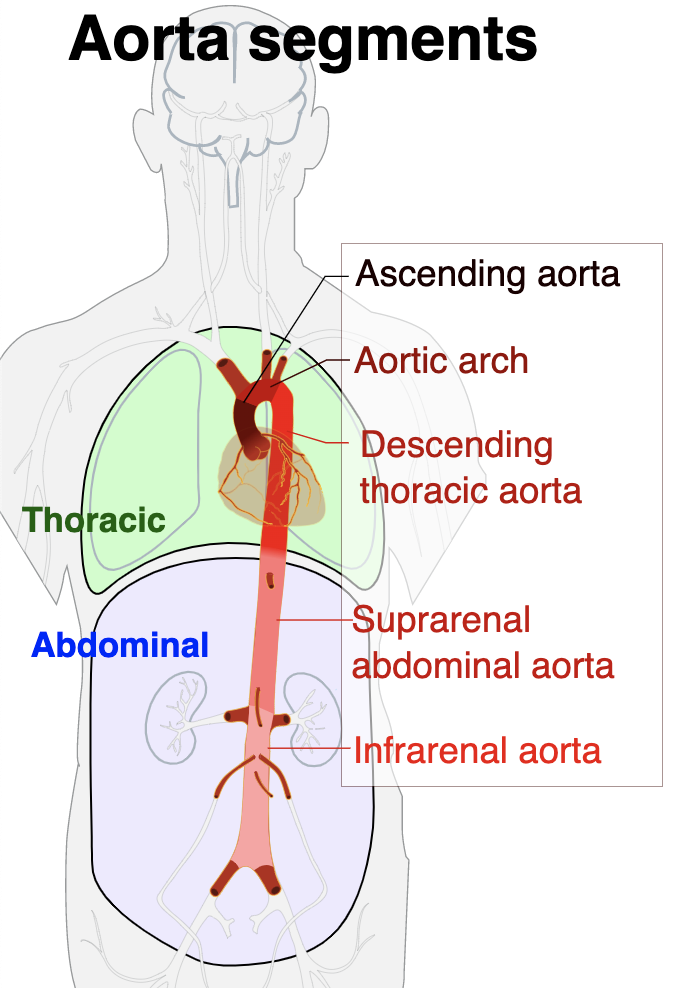

The aorta is the biggest artery in our body – I like to think of it as the main highway of oxygenated blood flow for our body.

It spans down our thoracic cavity, to our abdomen, and is responsible for getting blood to all the organs and tissues.

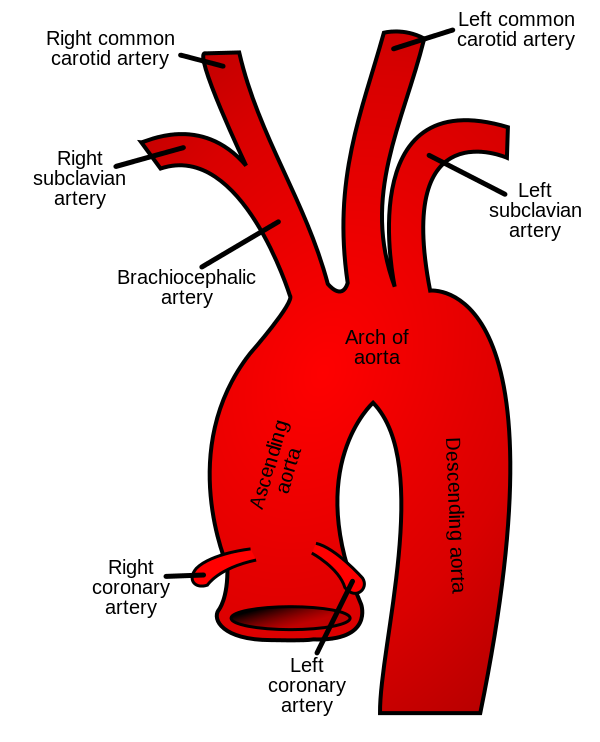

The problem……is that very early on in that aorta, are the vessels/arteries that feed our brain.

If you look at the photo above, you can picture blood leaving the left ventricle and entering that ascending aorta.

At that top of the aortic arch – you’ll see the branching off of the carotid arteries, the brachiocephalic artery, etc.

These arteries go up and feed the brain.

So to reiterate, if you get a big ol’ clot in your left atrium, that clot can travel down to the left ventricle, out the heart, up the aorta, and immediately up into the brain.

This causes what we call an ischemic stroke. By lodging in your brain arteries and blocking blood flow to your brain, you then deprive your brain of oxygen. No oxygen means no tissue perfusion, means death of tissue.

Besides having the potential of being fatal, ischemic strokes can also cause some serious patient morbidities – loss of motor function, ability to speak, you name it. So often times even if your patient survives, their quality of life can be greatly reduced.

Ok, so: we want to prevent ischemic strokes in patients with atrial fibrillation.

In order to do this, we’re going to have to give these patients medications that prevent that clot from forming in the first place – right?

Well, if you remember our talk on Clot Formation 101: An Overview, you’ll remember that a clot is formed by the coming together of both the clotting cascade and the platelet pathway.

Drugs that target the clotting cascade are known as anticoagulants, and drugs that target the platelet pathway are called antiplatelet agents.

So, which type of medications do we give and why?

Antiplatelets or Anticoagulants?

Luckily for us, this debacle was studied and researched. Back in the day (our pre-DOAC days), all we really had as an oral anticoagulant was warfarin.

So we looked at this question – what’s better at preventing stroke in these patients? Aspirin (antiplatelet therapy) or warfarin?

When comparing these two agents in patients with afib, we found that anticoagulation with warfarin was waaaaaay more effective, with warfarin reducing AF-related stroke by 64% versus 22% for aspirin therapy.

Not only that, but the benefit of reducing strokes in these patients far outweighed the bleeding risk that warfarin brought to the table.

Alright, alright – so we should anticoagulate these patients.

But should everyone with atrial fibrillation get anticoagulants?

To answer this question, you first have to understand the difference between valvular atrial fibrillation and non-valvular atrial fibrillation.

Valvular versus Non-Valvular Atrial Fibrillation

Atrial fibrillation is broken up into different “classes”: patients that have atrial fibrillation due to valvular disease and those who have atrial fibrillation from other causes.

Valvular Atrial Fibrillation is the presence of afib in patients that have any of the following:

- A mechanical (metal) heart valve in any position (this means that it doesn’t matter if the mechanical heart valve replaced your mitral valve, or your aortic valve etc. If you have a mechanical heart valve anywhere in your heart, you have valvular afib)

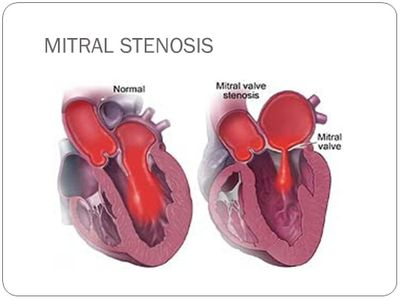

- Moderate-severe mitral stenosis. Whenever you hear the term stenosis, I want you to think of a narrowing. Mitral stenosis is the name we give for patients with mitral valves that are narrowed – often due to calcification due to age. Instead of being able to nicely open wide and close, the valve is all tough and cannot open up wide.

If your patient doesn’t have any of the above (including if they only have mild mitral stenosis), then we consider their afib to be non-valvular.

Why do patients with moderate-severe mitral stenosis have afib?

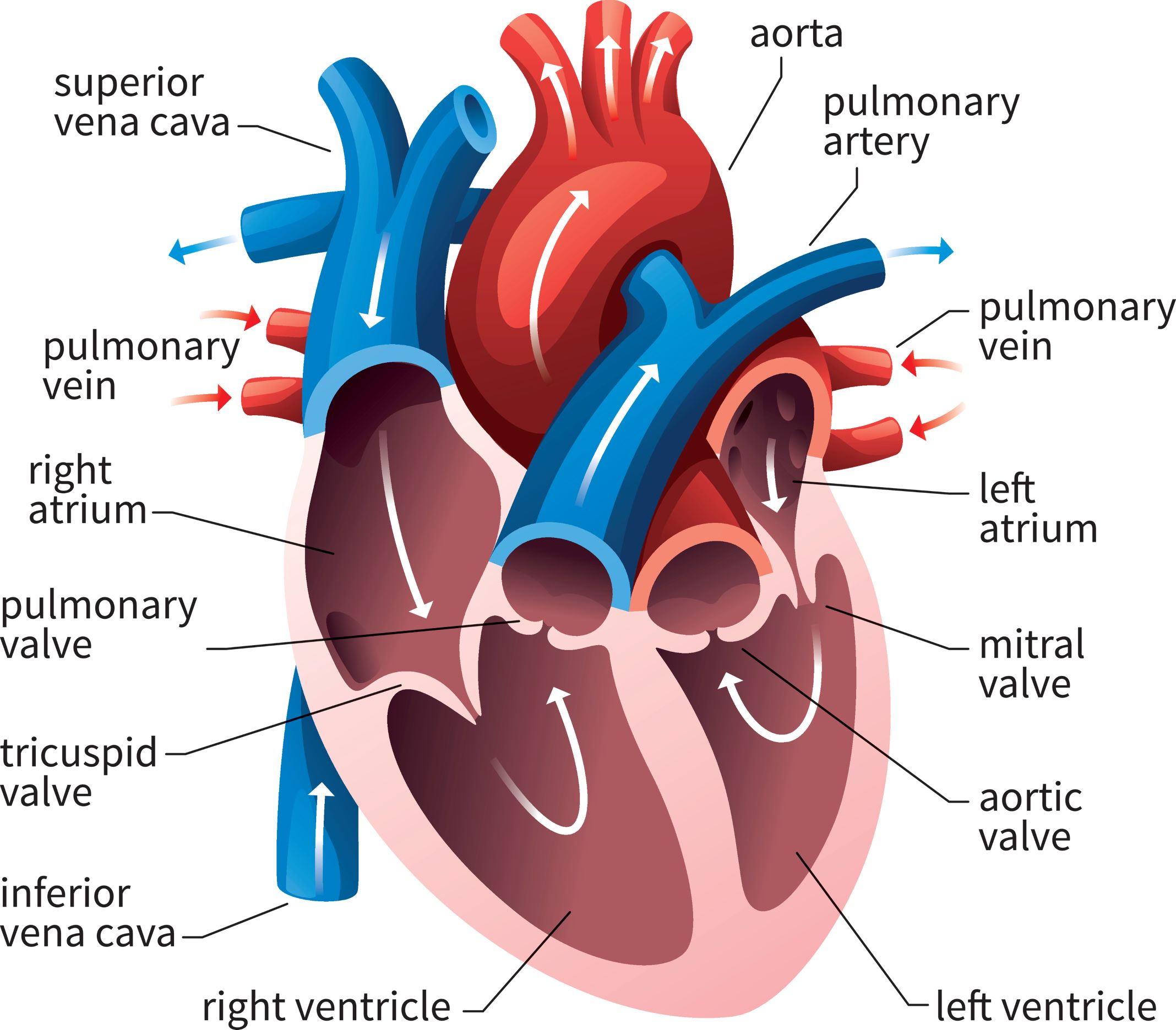

In order to answer this, I’m going to pull up a picture of the heart.

A ✨friendly✨ reminder that the mitral valve sits in between the left atria and the left ventricle.

In healthy patients with normal mitral valves, that mitral valve is nice and patent and opens WIDE. Because of this, the left atria can easily push out the blood it has been collecting out into the left ventricle.

No issues.

But think about what happens when that valve gets really calcified, stenosed and narrowed. Now, instead of a nice, wide opening….we end up with a teeny tiny hole that that left atria has to get blood through.

What’s going to happen as a result?

I’m a super practical learner. You have to remember that your heart just doesn’t ✨know✨ what to do, despite what we might have thought in a million breakups when we were teens, amirite? Your heart follows simple physics when it comes to pressures and flow.

I like to think of mitral stenosis as blowing air through straws.

Let’s say you have a slurpee straw or like a boba straw. A nice thick straw. It’s fairly easy to get that air out of that straw right?

OK, well now try it again, but with those thin little black cocktail straws.

What’s going to happen? You’re going to try to blow air out, your cheeks are going to puff out, and it’s going to be way tougher to blow that air out right?

Your cheeks puff up because of a backup in pressure. The same thing is going to happen in bad mitral stenosis. There is going to be a build up of pressure in that left atrium as it tries to get that blood through that teeny tiny mitral valve opening.

Now, just like your cheeks, your atria aren’t built to withstand high pressures (like our ventricles can). So, as a result, your left atria is going to start ballooning out and enlarging.

If you recall our afib overview talk, anything that causes that atrial tissue to get pissed off, or stretched out can cause afib right?

This is why mitral stenosis, (and SPECIFICALLY mitral stenosis – not aortic stenosis not other types of stenoses) causes atrial fibrillation. The build up of pressures causes a ballooning out of that left atrium and WHAM, as a result – valvular afib.

Why do we care if our patients have valvular or nonvalvular afib?

So, why do we even care? Why take the time to do this categorization thing?

The risk of ischemic stroke is different in valvular versus non-valvular atrial fibrillation. And because of this, the treatments are also different.

Valulvar Afib: Anticoagulation Treatment

Patients with valvular atrial fibrillation have a much higher risk of stroke than patients with nonvalvular afib (some estimates are as high as 20% per year!)

Because of this, patients with valvular afib get warfarin. It’s hypothesized that warfarin may be more potent since it targets multiple clotting factors while our DOAC agents only target one.

To reiterate: if your afib patient has a mechanical heart valve AND/OR moderate-severe mitral stenosis, your patient should be treated with long term warfarin. Easy.

Non-valvular Afib: Anticoagulation Treatment

What about all of our other afib patients?

Our first step is to determine if they are “high risk” enough to qualify for anticoagulation. After-all, everything in medicine is risk versus benefit. All anticoagulants carry a risk of bleeding, and we want to make sure the benefit in stroke reduction is much higher than the risk of bleeding in our specific patient.

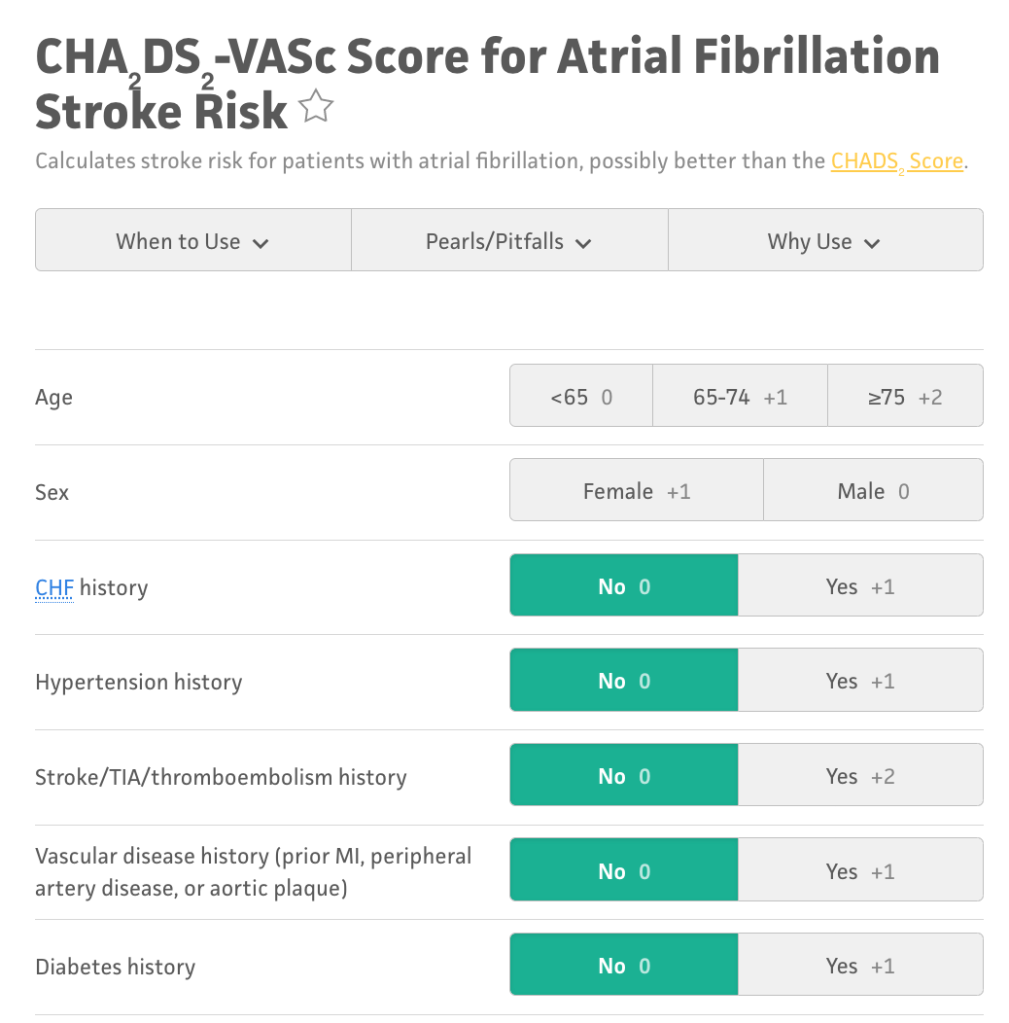

To do this, we have an evidence-based fancy scoring system called the CHA2DS2-VASc. The CHA2DS2-VASc is a scoring system that includes many of the highest risk factors for stroke and gives us an idea of what our specific patient’s risk is for getting a stroke. More specifically, it estimates what your patients risk of having a stroke is per year.

I recommend you guys take a minute and try the calculator out for yourself. Here is an example from MDCalc.

When your patient develops nonvalvular afib, you should run their specific stats through the CHA2DS2-VASc scoring system to get an idea of that specific patients risk for having a stroke.

The rule of thumb is that in male patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 2 or higher, the benefits of anticoagulation outweigh the risks. Similarly, in female patients with a CHA2DS2-VASc of 3 or higher, the benefits of anticoagulation outweigh the risks.

If you take a second to actually look at the criteria, you’ll find that the vast, vast majority of patients with non-valvular atrial fibrillation should receive anticoagulation. In other words, despite the fact that anticoagulation increases the risk of bleeding, the benefit of preventing ischemic strokes FAR outweighs the risks of bleeding in these patients.

Good news for these patients. For the longest time, as I said before, all we had was warfarin. But in the 2010s, we finally got a new class of anticoagulants – the DOACs. DOACs stand for Direct Oral AntiCoagulants and encompass apixaban (Eliquis), rivaroxaban (Xarelto), dabigatran (Pradaxa), and edoxaban (Savaysa).

Now, whenever we have new drugs, we don’t really know how they compare with our old treatments right?

To test them out, we compared them to our standard of care at the time (warfarin) and saw that they had just as good protection against ischemic stroke, but a much lower rate of bleeding, most importantly, brain bleeding (aka hemorrhagic stroke).

In other words, these agents were just as good as warfarin to prevent strokes in our patients and they also carried a much lower rate of bleeding than warfarin.

Because of this, the latest set of American Afib Guidelines, now recommend DOACs OVER warfarin to prevent strokes in patients with nonvalvular afib. Because of this, millions of non-valvular afib patients switched from warfarin to DOACs because they are just as effective and safer.

Let’s do some summarizing:

- Ask yourself: does my patient have nonvalvular or valvular afib? If you’re not sure, look at the patient’s latest ECHO. Afterall, if your patient has nonvalvular afib and they are on warfarin, switching to a DOAC is a great idea since they are not only safer, but don’t require routine blood monitoring and dietary restrictions.

- If valvular afib: Treat with warfarin with an INR target of 2-3.

- If nonvalvular afib: Calculate a CHA2DS2-VASc score. If indicated (and most will be indicated), start a DOAC.

What do we do in patients that need anticoagulation but keep bleeding on them or have a high baseline risk of bleeding?

Let’s say you have a patient on their Xarelto and they just keep experiencing moderate to severe bleeds. They are indicated for anticoagulation because we want to prevent those strokes from happening, but at the same time, they keep bleeding.

What can we do for these patients?

Well, remember our left atrial appendage? If you recall, this is one of the major spots where blood clots form.

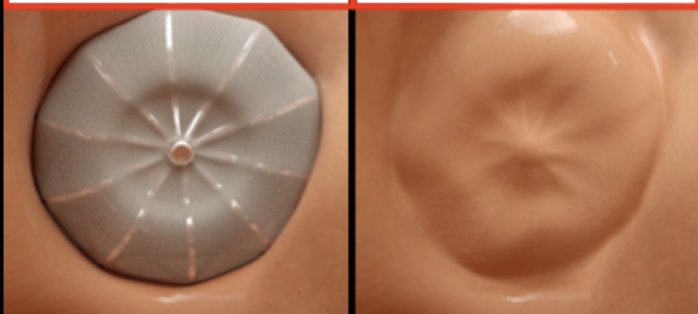

In patients like this, we can actually put in a device that closes off this left atrial appendage. This device is called a Watchman. Check out the video below.

A Watchman is a tiny implant that is put in via catheter and is a fairly noninvasive procedure. In this procedure, the interventional cardiologist will thread a catheter through your femoral vein, up through the inferior vena cava to the right atrium.

The doc will then poke that catheter through the septum (wall) between your right and left atria to access the left atrium. They will then insert the device into the left atrial appendage and will deploy the device.

Once deployed, the catheter is taken out. If you were sitting in your patient’s left atrium at this point looking up at where their LAA used to be, you’d see this:

Perfect! Appendage closed, stroke risk mostly removed, we’re good right?

Well, not exactly. What do you think is a potential complication of the blood in your atria now touching and hitting against this new foreign device?

If you guessed clotting, you’d be right.

In order to prevent clotting on the device surface, patients have to complete a fairly short course (~45 days) of warfarin after this device is implanted.

Kinda ironic right? We implant this to get off of anticoagulation, but the device itself carries a risk of clot formation and requires anticoagulation in and of itself.

Over this period of time, the body will actually grow a layer of tissue (endothelialize) over this device so that if I were to look from the same view after a few weeks, I’d just see a normal heart tissue wall.

Now that no more foreign material is exposed, the thrombotic risk is gone, and your patient can finally be anticoagulant-free for their Afib. Wahoooooooooo 🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉

This treatment is not as effective as anticoagulation – which is why you don’t see it super, super often- but still eliminates the majority of risk of stroke in these patients.

But because you need anticoagulation immediately after Watchman implantation, you wouldn’t want to rush to do this procedure after an Afib patient on anticoagulation comes in with a major bleed.

Other, more aggressive LAA Occlusion Methods

Watchman devices are great because, like I said, they are fairly noninvasive.

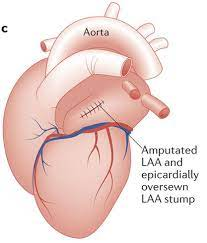

However, if you are going in for an open heart procedure – let’s say you need a bypass surgery, or a valve replacement, etc. – more often than not, cardiothoracic surgeons will take the opportunity while they’re in there to do a kind of “one-stop-shop”.

While they’re in there, these docs will often just clip off or sew that LAA closed.

This is obviously way, way more invasive – I’m talking about ribs cracked open, heart exposed, etc. No patient is ever going to undergo this procedure just for their LAA/afib – that would be pretty unethical when we have other options like the Watchman – but if they’re going in there anyway for important procedures, you will often see this done as well. Just something to be aware of in the world of cardiology.

So – that’s it for chronic afib anticoagulation. In my next post, I’m going to cover anticoagulation for more acute afib situations and talk about how we anticoagulate in the period surrounding cardioversion of these patients. Until then!

3 thoughts on “Atrial Fibrillation: Chronic Anticoagulation 💊”