“Required” readings to help understand what I’m talking about:

Atrial Fibrillation: Chronic Anticoagulation

Hey guys! I’m already back – but figured it would be good to finish the afib anticoag talk while it’s still fresh in your head.

Spring has started really hitting the northeast, where I am in Jersey. My dogs have been loving this weather and so have I.

I’ve personally been obsessed with looking at the birdfeeder we put up outside of our house (realizing more and more I’m becoming a 90 year old at heart). We have this woodpecker in the neighborhood who likes to get a bite to eat and then peck at our house and it drives my husband crazy.

What better way to celebrate the nice weather than grabbing a cocktail, getting your cell phone and skimming over a post on anticoagulation in acute atrial fibrillation? (I could use a gin, tonic & lemon myself).

Today we’re going to focus on more time-pressing concepts, like – how do we know when to start anticoagulating a patient in the hospital that goes into atrial fibrillation? What if we have to cardiovert them? What if they need to go for a procedure or surgery?

We’re also going to get our feet a little wet in interpreting drug literature towards the end of today’s discussion.

Let’s talk about each scenario and tackle these babies one at a time.

My patient (w/o a history of afib) just went into Afib! 😨😨😨😨😨😨😨

Do I start the heparin gtt?!

Hold your horses, buddy.

Let’s boil it down back to pathophys.

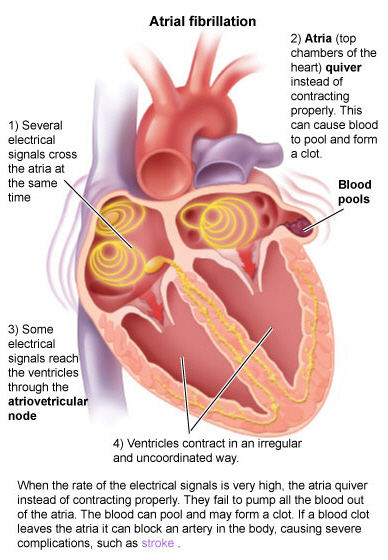

What is happening in afib? What is the etiology for that clot forming?

If you remember, clots forming in afib are a result of a slowing down of blood in that left atrium. Remember that there’s no site of injury or foreign object or immediate reason the clotting cascade would form a clot in that atrium. Instead, it’s a slower process due to blood that is more stagnant than it should be.

If my patient happens to have a brief run of afib, that doesn’t mean *BAM* clot formed.

Again, very, very different pathophys compared to something like an ACS event, where your patient has their coronary artery wall rupture, tissue factor releases, and immediately triggers that clotting cascade and thrombus formation.

In other words, it takes time to have this clot form in afib.

And time is exactly the factor we take into consideration when we think about when to start anticoagulation in these patients.

The general rule of thumb is to wait until your patient has been in afib for >48 hours to start anticoagulation.

The thought process was that it would take around 48 hours for a clot to develop in that left atria. This “48 hour rule” was adopted back even before the 90s.

Like many other things in medicine, though, the “48-hour rule” was adopted mostly based on theoretical rather than data-driven grounds. Afterall, if we waited for data to come out on every single little thing instead of applying our best clinical knowledge at the time, we would be doing our patients a disservice.

Luckily for us, people way smarter than me finally decided to take a closer look into this long-practiced rule back in the 90s.

They looked at n=375 patients who had afib for <48 hours and found that only a very small percentage (~0.8%, n=3) had a clinical thromboembolic event, supporting the current recommendation in these patients. 🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉🎉

Remember that a lot of patients in the hospital go into afib, but a lot of them will self-resolve or resolve quickly, since that afib is due to more acute causes (e.g. infection, volume overload, inflammation, etc) instead of permanent things like structural heart disease.

We don’t want to go around throwing on heparin drips (gtts) on every single patient because keep in mind that we also don’t want to put them at unnecessary risk for bleeding if they don’t need it. Also – do we really want to do that to the real MVPs of the healthcare team – the RNs? Continuous drips are lot of work. I think not.

(PSA: take some time out to thank your nurses today. Anyone ever in medicine knows that we would not be able to function without their hard work.)

Anticoagulation Surrounding Cardioversion

Cardioversion is when we restore a patient’s normal rhythm. In other words, we get them out of their afib and back to how their heart is supposed to be conducting. We can achieve this in two ways: with electricity ⚡⚡⚡ or with medications 💊💊💊.

We tend to prefer to cardiovert a patient who is “early-on” in their afib (eg hasn’t had a long standing history of afib) because data actually supports that the earlier on we cardiovert, the more likely we will be successful at getting that patient back to normal sinus rhythm (NSR).

This should hopefully make sense to you based on our previous discussions.

Remember that afib in and of itself can cause structural changes to your heart over time.

That left ventricle will work harder than it should over time and grow, or hypertrophy. I’ve said it a million times but your heart is a muscle like other muscles and if you went to the gym and worked out those muscles, your biceps would grow. Your heart is no different.

And remember that unfortunately, structural changes are irreversible.

We can clone a sheep named Dolly, but we still haven’t figured out a way to reverse time and tissue remodeling in our patients’ hearts. The more structural changes, the more likely that your patient’s afib is going to be permanent.

OK – next question: why are we even worrying about anticoagulation during cardioversion?

…Remember that thrombus/clot that we said can form in the LAA/LA when a patient is in afib?

Well, while that patient remains in afib and the atria just quiver, that clot isn’t going to easily go anywhere, since it isn’t receiving a lot of force from atrial contraction. It’s likely just going to hang out dancing around in that left atrium or left atrial appendage.

But when we cardiovert a patient from afib back into normal sinus rhythm, that atria reverts back to its normal contraction. Which means that clot, that has been kinda sitting there hanging out, can now more easily get pushed out of that LA, into the LV, through the aorta, and up to the brain to cause a stroke.

Which means that cardioversion carries along with it, a big risk of stroke.

Luckily for all of us, I feel like the rules surrounding anticoagulation during cardioversion are pretty self-explanatory.

The first thing you want to assess when you have a patient with afib that you want to cardiovert is: are they stable?

Is your patient sitting there talking to you or is their HR 205, with a BP of 89/46 mmHg and they’re looking a Voldemort-level-of-pale?

If they are stable – great: you have time to think things through.

If they are unstable – unfortunately at this point we have to assess risks vs. benefits.

Yes, there is a chance that this afib in your patient is not new, and has been around for >48 hours.

There is a chance that a clot has manage to form in that patient’s LA, but if you don’t do anything fast, that patient is not going to be able to get enough oxygen to their brain and vital organs.

When unstable: Cardiovert.

What about if they are stable? What do we do next?

This now just boils down to time.

If you know for a fact that your patient’s afib is brand new and they’ve been in afib for <48 hours, you can safely cardiovert.

Now for the patients with chronic afib (or afib for an unknown duration of time) who are stable, we have two options:

- We can put them on anticoagulation (if they have not been on it), for a period of at least 3 weeks. We want to make sure they don’t have any clots hanging around the LA. After these three weeks, we can then cardiovert them safely.

- We can actually find out if they have a clot already in that LA. We can do this by getting an echocardiogram (an ultrasound that helps us visualize the clot).

- If we see a clot: you better believe we’re going to hold off. This patient (just like the patient above), will go through their 3 weeks of anticoagulation prior.

- If there is no LA thrombi visualized, we can cardiovert.

Now I’m no ECHO expert as a clinical pharmacist, but this is an ECHO so bad even a pharmacist can read it.

The stuff of nightmares.

Source: GFYCAT

Now, no matter if your patient was on anticoagulation prior to the cardioversion or if they weren’t, you better start that heparin gtt asap post cardioversion.

Remember that cardioversion in and of itself carries a risk of stroke; this means erryone who gets cardioverted should get therapeutically anticoagulated immediately afterward. Anticoagulation should continue for a period of 4 weeks post cardioversion – this is assuming, of course, that your patient converts to NSR and stays in NSR. Unfortunately, if your patient reverts back to Afib, we’re exactly back where we started, and anticoagulation should continue indefinitely. Poop.

What to do with anticoagulation for procedures

Our last topic in anticoag in atrial fibrillation is going to touch on our patients with afib going for procedures.

The dilemma here is that we know our afib patients carry a risk of ischemic stroke – hence their anticoagulation – but we definitely don’t want our patients to be therapeutic when they go for an invasive procedure….because….bleeding.

So the question is – what do we do to manage these patients?

We really have two options to consider:

- We can have them discontinue their oral anticoagulant, let it wash out prior to the procedure, leaving them at low bleed risk for their procedure. This sounds good but theoretically we can be risking them getting a new clot in the period between stopping their oral anticoagulant and the procedure.

- We can have them discontinue their oral anticoagulant, and start them on a “fast-on fast-off” IV anticoagulant like IV heparin. Something like this sounds good because we can “bridge” them with anticoagulation in that time before their surgery, and because it’s “fast-off”, we can stop the drip 6-8 hours prior to their procedure to ensure it’s all washed out by the time they hit the OR.

Decisions, decisions. What’s a girl to do?

First things first – it’s important to understand the clinical difference in possible thrombosis in a patient with chronic afib versus a patient who just had an active clot – like a patient with a recent history of DVT.

You have to remember that the risk of clotting in afib is fairly low per day.

An example:

A patient with a CHA2DS2VASC of 4 estimates that your patients yearly risk of clotting is ~4.8% (run the calc yourself if you want).

What this translates to is roughly a 0.013% chance of having an ischemic stroke per day.

Sounds insignificant right?

What the heck have we been doing?!

SOUND THE ALARM, WE SHOULDN’T BE ANTICOAGULATING THESE PATIENTS WEEWOOWEEWOO!!!!!

But you have to keep in mind that afib is a chronic condition.

Sure, their daily risk might sound small, but chances are, over the years, over decades, that seemingly small risk of having a stroke, will catch up to you. This is why, although small, patients with afib are characterized as having a 5x risk of ischemic stroke versus those without.

Breaking down these patients and really getting a true idea of what their risks are is so integral.

Back when I was in school, as a baby pharmacist, I used to think – therapeutic anticoag is therapeutic anticoag.

It’s all the same.

My patients with DVTs get therapeutic anticoag and my patients with afib get therapeutic anticoag so they must all have similar risks of clotting.

That’s just not the case. Patients with a recent, active clot are way more thrombotic than patients with chronic afib.

Now back to our clinical conundrum.

Luckily for us in 2015, we finally got some data that looked at this exact question – in the NJEM “The BRIDGE trial.”

The authors start off their paper acknowledging that clinical question; that “it’s uncertain whether bridging anticoagulation is necessary for patients with atrial fibrillation who need an interruption in treatment for an elective operation or other elective invasive procedure”.

They conducted a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial in which they split the groups: half the patients would d/c their oral anticoag cold turkey, and the other half would discontinue their oral coag and start on a heparin gtt as a “bridge”.

They had a pretty strong n=1884, and they looked at both arterial thromboembolism and major bleeding.

And?

“In patients with atrial fibrillation who had treatment interrupted for an

elective operation or other elective invasive procedure, forgoing bridging anticoagulation was noninferior to perioperative bridging with low-molecular-weight

heparin for the prevention of arterial thromboembolism and decreased the risk of

major bleeding.”

Alright, easy. So basically this trial is telling us that IV anticoagulation really didn’t change the rate of stroke (e.g. did not decrease strokes) in these patients but really, just increased the risk of bleeding.

I think it’s easy to say “ok cool” and put this one away.

But, like any publication, you should always make sure to understand exactly what type of patients we’re talking about here.

In a study like this, what is important to understand?

Well, because we are worried/looking at the rate of both clotting and bleeding events in these patients, we should figure out just how thrombotic or just how risk of bleeding these patients were at baseline that were actually studied.

So the first thing to consider – did this trial exclude patients with a history of bleeding and/or at high risk of bleeding?

When we open up the supplementary appendix and check out our exclusion criteria, you’ll see that they excluded patients with a history of major bleeding within the past 6 weeks, platelets <100, and patients that are getting super high risk of bleeding procedures (e.g. cardiac surgery, neurosurgery, brain biopsy, etc)

Now you have to stop and think and assess what this means for the trial and its results.

Put it in simple terms.

Do we think that these exclusions got rid of a ton of patients? Did it leave us with a very, very, very specific niche of patients that are totally at low risk of experiencing bleeding in this trial?

Or is this exclusion criteria practical and representative of a somewhat “normal” patient population we’d encounter?

I’d argue that these exclusion criteria are very reasonable. Afterall, we’re not excluding patients with a history of any bleeding spanning years back. We’re not excluding Suzie our normal afib patient that had a history of nose bleeding two years ago. We’re being more practical – as long as you aren’t getting a huge procedure, have low platelets, and didn’t just have major bleeding, you’re in.

OK so we’ve figured out the relative bleeding risk of these patients -what about their thrombotic potential?

They did exclude patients with an ischemic event within the past 12 weeks, but again, very reasonable. We wouldn’t want to gamble with these patients and put them into a randomized group.

What else can we look at?

This is where checking out our relative baseline characteristics come into play. We know that concomitant antiplatelet agents put our patients at higher risk of bleed, but as long as our patients have similar rates of antiplatelets between groups, we should be good – which is what we see.

I think it’s also great that we had about ~30% of patients on something like aspirin – since this is a very “real-life combo”. It would be trickier to interpret these results if they excluded all patients with concomitant antiplatelets.

But what else would you’d want to check out about these patients. Is there any scoring system we use to estimate an afib patient’s yearly risk of stroke?? 👀 👀 👀 👀 👀 👀 That could give us an idea of what these patients looked like clinically.

Hopefully you remember from our previous discussions that we clinically use the CHA2DS2-VASc score to estimate ischemic risk in non-valvular afib patients.

Now, back in the day circa the BRIDGE trial, we still were using something called the CHADS2 score, which didn’t yet corporate sex or hx of vascular events (like MI, PAD, etc), but luckily for us, the investigators were smart enough to include this data too.

Checking out the baseline characteristics you’ll see that most patients were men (very typical in trials) and only about 14% had a history of MI, making these reported CHA2DS2-scores pretty accurate.

When you look at the breakdown of the CHADS2 score you’ll see that the mean score was 2, with a distribution as follows:

- 0: <1%

- 1: 23%

- 2: 40%

- 3: 24%

- 4: 10%

- 5: 2%

- 6: <1%

Now, is a CHADS2 score of 2 very thrombotic? Or are these pretty low-thrombotic risk patients as afib goes?

With a scoring system that went to 6, I’d argue that this trial mainly evaluated patients that had a fairly low risk of stroke.

Tying it all together

As with any article, having a good but fundamental grasp on what these patients looked like clinically is so important.

Because we know the patients in the BRIDGE trial had a fairly low risk of clotting and a normal risk of bleeding, I would argue to look at two things when approaching bridging.

- Is the procedure the patient’s going to get have minimal risk of bleeding? If yes, you can consider continuing anticoagulation.

- If no, the risk and question of bridging becomes more pertinent. Now is when I would argue you should assess the patients thrombotic risk. Since we really didn’t have data in patients with high thrombotic risk, I’d argue that if your patient has a higher risk of clotting – you can consider bridging that patient with IV heparin. However, if they were more representative of the patients in the BRIDGE trial – with a CHADSVASC of ~3-4 or less – hold off to avoid that unnecessary bleed risk.

AAAAAAAANDDDDDDDDDDDDDD I think that’s enough about anticoag in afib.

I’d also love to get some feedback on the blog and how I’ve been doing.

If you’re enjoying this blog, please consider sharing with your colleagues or friends/fellow students!

Appreciate the in depth reviews! Glad I had looked this over recently as I had a newer RN ask me why we don’t just cardiovert a patient!

LikeLike