Today we’re talking rhythm control (it’s kinda a doozy, sorry in advance, love u). In order to get the most of out today’s talk, I recommend these previous “pre-readings” of sorts:

The Cardiac Conduction Cycle and the Cardiac Action Potential

Atrial Fibrillation: An Overview

Atrial Fibrillation: Chronic Anticoagulation

Atrial Fibrillation: Acute Anticoagulation Part 2

Atrial Fibrillation Tx Part 1: Rate Control

What is rhythm control?

Rhythm control is when we attempt to not only convert a patient back into normal sinus rhythm but also to maintain that sinus rhythm. Unlike rate control, a patient that undergoes successful rhythm control is no longer in afib.

What are the ways we can obtain rhythm control in our patients?

There’s a bunch of different ways to try and achieve rhythm control in afib. These include ⚡electrical cardioversion ⚡, antiarrhythmic drugs 💊, radiofrequency catheter ablation 💥. It’s not uncommon to also use a combination of the above approach.

What is ⚡electrical cardioversion⚡?

The word cardioversion refers to the conversion of an abnormally fast heart rate (aka a tachycardia) to a normal rhythm. It’s important not to necessarily mix up the term cardioversion to only mean electrical cardioversion. Cardioversion can also be achieved by the use of medication.

When referring to electrical cardioversion, we are talking about using a therapeutic dose of electrical current directed at the heart.

In the treatment of afib, we use something called synchronized electrical cardioversion. In synchronized electrical cardioversion, we apply the shock at a specific moment in the cardiac cycle.

Why?

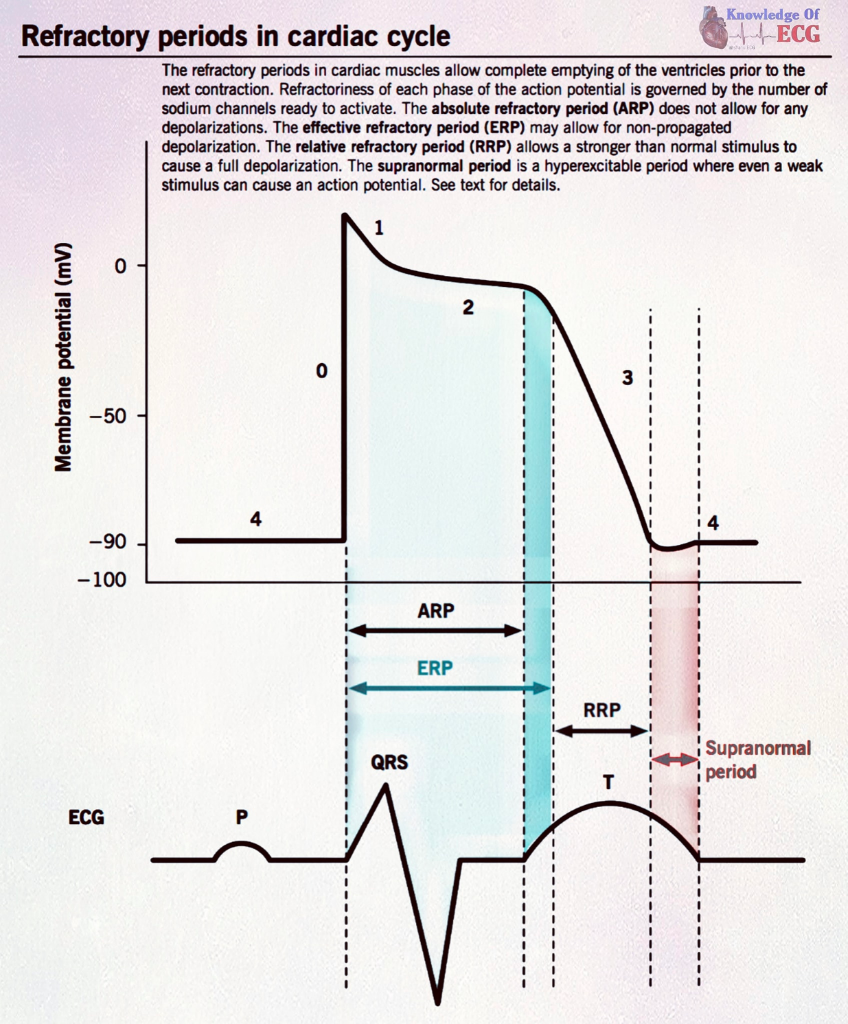

Well, if you remember back to our cardiac action potential – our P, QRS, and T waves – you might remember that there is something called a refractory period – this happens after the original impulse is sent to the ventricles and as our myocardial cells are repolarizing and relaxing.

Let’s review it: an electrical impulse gets sent to the ventricular cells – the impulse stimulates a depolarization or contraction. But during repolarization, we have a refractory period.

If you try to dust off the dusty cobwebs of the corner of your brain from college, you might remember that a refractory period is a period of repolarization where a muscle is relatively unresponsive to further stimulation.

The refractory period is made up of two different phases: the absolute refractory period and the relative refractory period.

During the absolute refractory period – NO stimulus, no matter how intense, can stimulate another new action potential.

However, during the relative refractory period, if a stimulus is STRONG enough, a new action potential may be triggered.

This period of relative refractoriness corresponds with the t-wave peak (apex) on the EKG.

Why is this bad?

Let’s say your patient is in afib and you accidently deliver an uncoordinated shock and it shocks the patient at the peak of that T wave – during the relative refractory period…

That shock may induce a separate stimulation of the ventricles, causing an early ventricular depolarization. Often this is seen as a premature ventricular beat (aka PVC) that can induce disruption of the ventricles but can also lead to ventricular fibrillation (aka a cardiac arrest). Not good.

For this reason, we use synchronized cardioversion to avoid shocking during this period of vulnerability and instead synchronize the shock with the QRS complex – when the heart is at its least vulnerable.

The machine will spit out 120-200 joules of energy to stop the afib and convert your patient to normal sinus rhythm (hopefully).

Another common misconception I get from learners is that the shock causes the afib to just morph into NSR. The truth is a little different.

Cardioversion actually resets the heart. It upsets and stops the abnormal signaling in the hope that the heart will reset back into normal sinus rhythm. It’s like resetting your computer – you have to stop it and shut it down in order for it to reset.

⚡Electrical cardioversion⚡ is a reasonable first line option for patients who are pursuing rhythm control. If that fails, often times we will try the combination of both antiarrhythmic medications to “prime” your patient and help them successfully convert with electrical cardioversion.

We also opt to use electrical cardioversion in the acute setting when patients present with a rapid ventricular rate response to AF and are hemodynamically unstable.

Keep in mind that electrical cardioversion is NOT only used in the acute setting. Like I said before, it’s a reasonable first line option for any patient pursuing rhythm control.

Oftentimes we will schedule a cardioversion for patients and have plenty of time to give them sedation and pain medications to make the process go as smoothly as possible.

Always remember that cardioversion has some specific anticoagulation requirements with it (mentioned in the pre reading).

The longer you have afib, the more structural damage that happens to the heart as that ventricle beats faster. This is why past a certain point, especially in older patients with structurally damaged hearts, their afib becomes permanent.

We can still try cardioversion in patients with persistent (not PERMANENT) afib, provided that it converts them for a clinically meaningful time between procedures. Once a patient has permanent afib, we no longer will try any rhythm control method, including cardioversion, since it is unlikely to be successful.

💊Pharmacological Cardioversion💊

Like I said above, drugz can also be used to cardiovert your patient. They can either cardiovert the patient in and of themselves or be given to help the effectiveness of electrical cardioversion.

Protip: pharmacologic cardioversion is most effective when started in the first week after an episode of AFib started.

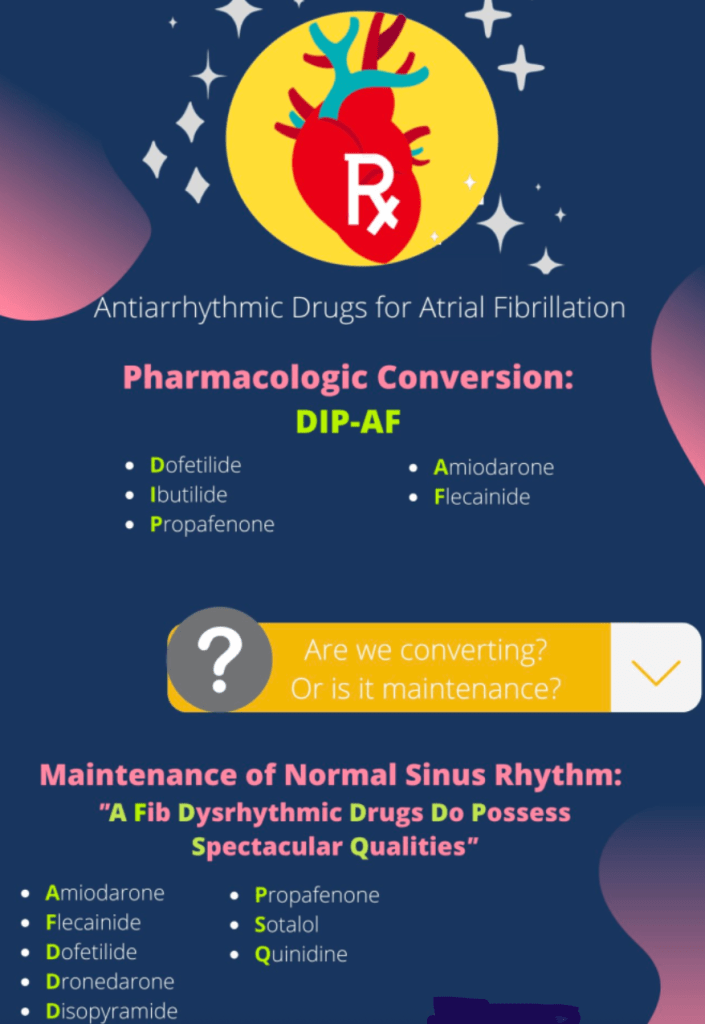

The other thing I think is also often forgotten is that there are different antiarrhythmic drugs used for cardioversion of afib versus for the maintenance of afib. Yes, there is some overlap, but some drugs that are used for maintenance are not used for conversion and visa versa.

Now, I’ve thought long and I’ve thought hard of ways to simplify what can be used for what. She’s not perfect, but the below is what, when in doubt, I personally use to help remember :

Now let’s talk about efficacy and practicality (and, you know…what data we actually have on these agents). Again, these are the meds we can use for cardioversion: our “DIP-AF” meds.

Pharmacologic Conversion: Ibutilide

Ibutilide is one of our IV options for pharmacologic conversion of AFib and is decently effective, with an efficacy rate of about 50% of the time when given in those with recent-onset afib with an average conversion time of <30 minutes.

These patients will get 1 mg of IV ibutilide over 10 mins and can get a repeat 1 mg one more time if needed (if your patients are small, <60 kilo, opt for the 0.1 mg/kg dosing instead).

Pretreating with ibutilide prior to electrical cardioversion also improves the likelihood ibutilide will work.

The biggest risk of giving ibutilide is QT prolongation as it can cause Torsades de Pointes (aka TdP), with an incidence of ~3-4%.

Patients who receive ibutilide have to be monitored via EKG for at least 4 hours post administration and have resus equipment nearby in the case that your patient is in that 3-4% and deteriorates further into a cardiac arrest.

Avoid in patients with severe hypokalemia, QT prolongation, or an ejection fraction less than 30% (all due to increased risk of ventricular proarrhythmia in these patients). Some people advocate to give some IV magnesium sulfate prior to ibutilide to help decrease this risk.

So overall (the TLDR version): ibutilide works decently if your patient is a candidate but a big con is that you need to monitor the patient for 4+ hours as it has a high risk of QT prolongation/TdP so may not ideal in an ED setting, for example.

Pharmacologic Conversion: Propafenone & Flecainide

Propafenone and flecainide are pretty cool options for patients with afib that are candidates for them. They are known as pill in the pocket therapy. This is basically for patients who can tell/feel when they are in afib.

With these therapies, they don’t have to take a maintenance antiarrhythmic everyday.

However, when they feel that they are in active afib, they can take their propafenone (or flecainide) pill out of their pocket and take it in that moment to restore normal sinus rhythm again.

Because this is technically an outpatient therapy that the patient will take on their own – and cardioversion has risks involved with it – like bradycardia, AV node dysfunction, or having a proarrhythmic response – we always like to do an initial conversion trial in a monitored setting to make sure this therapy is safe and effective before sending these patients out into the wild to take on their own.

Pharmacologic Conversion: Amiodarone

Amio is ….eh, kinda unimpressive by itself. We know amio has some beta blocking effects which make it good for lowering a fast ventricular rate, but it’s antiarrhythmic properties in the cardioversion setting…are not that great in the sense that they take a while to work (time delayed). Data shows that when oral amiodarone was loaded over the course of several weeks, only about 25% converted to sinus rhythm. Oral amiodarone can be used for cardioversion in a less acute setting, and is a reasonable option, but if you want a quick cardioversion…probably not your best bet.

Protip: the easiest way to remember your special “pill in pocket” drugs is to remember they are both class 1c antiarrhythmics.

Can’t get your class 1 antiarrhythmics down? I always recommend reverting back to the age old mnemonic:

Now, I used to know this whole burger thing and it was helpful but for some reason I always forget what came second: is it the fries? Do I add mayo now?

But the trick that always helped me was to remember: always finish making your burger FIRST before moving onto the sides (aka the fries please).

Speaking of our 1Cs (our pill in pocket therapy – our fries, please – propafenone and flecainide), you do not want to use these agents in patients with a hx of coronary artery disease (CAD) and structural heart disease.

The history of why is pretty interesting.

I think that it’s so easy to learn cardiology today and be like “OK and we don’t use these agents in XYZ” and think that we’ve always known these things.

Because medicine is so all-knowing and smart right?

The truth of medicine is that it takes a lot of trial and error, and good hypotheses don’t always lead to good outcomes. And in those cases….you live and you learn. And you’ll see what I mean.

Let’s take it back to 1991. Paula Abdul is on the radio.

The healthcare community had been noticing that patients that are status post myocardial infarction (aka after a heart attack) tended to have an increased incidence of premature ventricular contractions, aka PVCs.

PVCs are pretty common, even in you and me, and is the name for when a heartbeat is initiated in the Purkinje fibers in the ventricles rather than the normal SA node.

Usually they do not pose any danger and may either be completely asymptomatic, they may also be perceived as an “extra heartbeat” or a palpitation.

Have you ever just been chilling watching a show or reading a book and all of a sudden you feel your heart beat and pound for a couple beats?

……..

No?

Just me?

Well whatever, if so, what you’re probably experiencing is a PVC.

Anyway, back to our 1991 trial – the CAST Trial – aka the Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression trial. They noticed that patients s/p MI had an increased incidence of PVCs and investigators asked – if we suppress these excess ventricular ectopies in these patients – can we reduce the incidence of more severe ventricular arrhythmias and reduce sudden death in these patients?

Ok cool cool, so they randomized patients that were anywhere from 6 days to 2 years after their MI, had a lower EF (55% or less if within 90 days post MI or 40% or less if recruited >90 days out) and were randomized to either placebo or encainide (no longer on the market but was also a 1c agent) or flecainide.

We were hoping to see a decrease in mortality, save the day, and prevent death in our vulnerable post MI patients.

But…..

Instead…..

We had to stop the trial early.

Because, even though we suppressed these PVCs, we also found that our 1c agents significantly increased the rate of death and cardiac arrest (over 2.5x!) with a number needed to harm of 29 during a follow up period of only 10 months.

In other words, in less than a year, for every 29 patients you treated with a class 1c, you caused a death.

NOT. GOOD.

Thanks to this trial, class 1c agents are now contraindicated in patients with coronary heart disease or structural heart disease.

The other thing to know: when using a class 1c agent (aka flecainide or propafenone), your patient must first be on an AV-nodal blocking agent (e.g. a beta blocker, or non-DHP calcium channel blockers).

Why?

Our class 1c agents are able to slow down the atrial rate. That may sound good, but if the rate slows enough, you can end up with 1:1 AV conduction and an increased ventricular rate as a result. This is because even though these agents are slowly down atrial rate, the atria is still firing at a rate higher than what is normal, and can cause ventricular tachycardia if conducted 1:1.

Maintenance of Normal Sinus Rhythm and Prevention of AFib Recurrence

Ok, so we snapped our patients out of Afib, either with some electricity or some drugz or a combo of both.

Now we have to give meds to keep your patient in NSR and prevent them from going back into afib.

Cue the infographic again:

The following can all be used for maintenance of NSR, depending on patient specific factors: amiodarone, flecainide, dofetilide, dronedarone, disopyramide, propafenone, sotalol and quinidine.

However, our class 1a agents (disopyramide and quinidine) for AFib have been associated with a possible increase in mortality, so aren’t commonly used and not included in our first-first line options. Amio is also usually reserved for further down the line if possible due to long term adverse effects.

Drug selection for antiarrhythmics is driven to a greater extent by safety concerns than it is by drug efficacy.

Even the AHA guidelines say “a common approach [to finding the best agent for your patient] is to identify available drug choices by first eliminating…drugs that have absolute or relative contraindications.“

Does your patient have structural heart disease? Do they have coronary artery disease? Do they have heart failure or LV hypertrophy? Do they have risk factors or other meds that can cause QT prolongation? How’s their renal or hepatic function? These are all things that are going to help you narrow down what agents you can even use.

Efficacy:

With the exception of amiodarone which tends to be the most effective agent, the majority of the maintenance antiarrhythmics have an efficacy rate of about 30-50% at 1 year.

Specific Agent Review

Normal Sinus Rhythm Maintenance: Amiodarone

Because of its long term toxicities to almost every organ ever (jk but not really), amiodarone should only really be used after other agents have failed and/or are contraindicated. Amio is a pretty dirty drug in that it hits multiple ion channels – Na, K, Ca, and also has better blocking properties. It also has a super long half life and distributes widely into adipose tissue. Amio tends to take days to weeks to have its antiarrhythmic effect and QT prolongation. If you “load” with amio (aka give higher doses in the beginning to reach steady state faster) , you can accelerate its onset of activity. Amio also has a lot of drug-drug interactions because it inhibits liver enzymes CYP3A, CYP2C9 and also P-glycoprotein, so can mess with the metabolism of other drugs like warfarin or digoxin. When in doubt, DDI checker-it-out. In terms of long term efficacy for maintenance of sinus rhythm, amio is actually pretty damn good. In patients with paroxysmal or persistent AF, it performed better than dronedarone, sotalol, and propafenone.

The biggest CV side effect of amio is bradycardia. Even though QT prolongation can occur, we almost never see it inducing Torsades de Pointes. Because of its long term toxicities (thyroid, liver, ocular, dermatologic, pulmonary, etc), we don’t like to use it first-line, especially in younger patients when we have other options. Many toxicities are dose-rated but can be fatal. To prevent this, lower oral doses of <200 mg PO QD can be given chronically and may still be effective and have less side effects. Obviously, routine surveillance of these organs should be done. In those with LV hypertrophy, HF, CAD, and/or previous MI, amiodarone has a low risk of arrhythmias, make it a good initial agent in these patients.

Normal Sinus Rhythm Maintenance: Flecainide and Propafenone

I’m just going to group these two together here. If you remember from above, these are our Class IC drugs (Fries Please!) and (if you also remember) can only be used in patients with AF without structural disease. Flecainide and propafenone also have negative inotropic properties (decrease the force of contraction of the ventricles) and should be avoided in those with LV dysfunction. As we said above, these agents have to paired with AV nodal blockers due to the risk of atrial slowing causing 1:1 AV conduction. These agents can also cause up to a 25% increase of the PR and QRS intervals – but when a greater increase is seen in the QRS duration, it may be a marker for proarrhythmia risk. Use caution with these agents in patients with significant conductions system disease. Both agents are pretty well tolerated and if they do cause side effects, though uncommon you can see dizziness or visual disturbances with both and a metallic taste with propafenone. Both flecainide and propafenone have beta blocking properties, but their metabolites are electrophysiologically active with weak beta blocking properties. This might come in handy to know especially when it comes to propafenone and CYP2D6 – propafenone is a substrate of CYP2D6 – up to 7% of patients do not possess CYP2D6 (we call these peeps poor metabolizers) – and other drugs such as antidepressants, quinidine, fluoxetine, etc can also inhibit this enzyme leading to more than expected beta blockade.

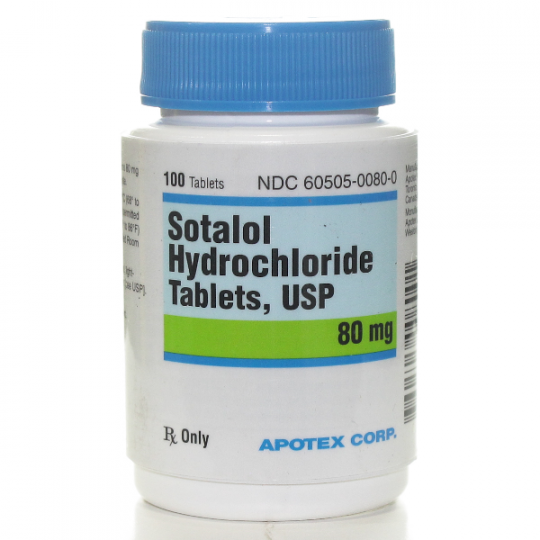

Normal Sinus Rhythm Maintenance: Sotalol

Sotalol: If you noticed in the infographic, sotalol is one of the agents that is not used for cardioversion but can be used for maintenance of NSR. This is because it is ineffective for pharmacologic conversion but does serve a role in maintaining that NSR. The important thing to remember with sotalol is that it can cause QT prolongation and TdP (a pretty high risk compared to our other agents) and also that it is renally cleared. Because of this, it should either used with caution or outright avoided in patients with chronic kidney disease or unstable renal fxn. Because of its high risk of QT prolongation and TdP, it used to be required to be initiated in the hospital setting. Even though its not required anymore, I’d say a lot of providers still initiate it in an inpatient setting and monitor EKG for QTC prolongation for the first few days of therapy. Make sure to periodically monitor potassium, magnesium and renal fxn in patients on sotalol.

Normal Sinus Rhythm Maintenance: Dofetilide

Dofetilide is one of our class III (K blocking) antiarrhythmic agents.

Because of the risk of QT prolongation with this drug, it is only considered for rhythm control in patients who are deemed low risk for torsades de pointes due to QT prolongation.

Dofetilide is pretty well tolerated and has very minimal non-cardiac side effects. Besides amiodarone, dofetilide is one of our more efficacious agents – one trial showed that it had a 58% efficacy of maintaining NSR at 1 year post cardioversion (with a 0.8% incidence of Torsades). In another trial of patients with HFrEF, it had an efficacy of 79% at 1 year in maintaining NSR.

Like sotalol, it has that high risk of QT prolongation, and it is still mandatory to initiate this agent in an inpatient setting when either 1) initiating therapy or 2) escalating the dose. I remember seeing my first dofetilide patient in the hospital during my clinical student rotations. He was just a “normal” looking guy – not sick, not fatigued, not anything – that in any other scenario, would not be in the hospital. But he just had to chill out in his hospital bed and sit there while we started his dofetilide therapy – he’d take a dose, get his EKG monitored – and then sit and watch movies until his next dose. Just like sotalol, dofetilide is also renally adjusted, dosed by CrCl, and dose adjusted and/or discontinued based on the degree of QT prolongation.

Normal Sinus Rhythm Maintenance: Dronedarone

Dronedarone: You might be asking yourself – why does this drug sound suspiciously like amiodarone? It’s because it’s an analog of it – and lacks its iodine moiety. Because of this, dronedarone is better tolerated and has less side effects than amiodarone.

Even though it’s better tolerated than amiodarone, it’s also much less efficacious. Dronedarone should not be used in patients with HFrEF because it was found to increase the likelihood of stroke, MI, embolism or CV death. It should also not be used in patients with NYHA class III or IV HF and in patients who have had an episode of HF decompensated within the past 4 weeks, especially those with low EF.

Dronedarone is also a messy drug like its cousin amiodarone, and also has beta, sodium, calcium, and potassium blocking properties. Although it has a lot fewer side effects compared to amiodarone, it can still cause bradycardia and QT prolongation. Torsades de Pointes is rarely seen with dronedarone (just like amiodarone) but it has been reported.

Just like amiodarone, it has multiple drug-drug interactions with CYP3A4, CYP2D6, and PGP so again, this is one agent you’ll want to run a DDI checker on. Unlike amiodarone, dronedarone does not alter the INR when used with warfarin.

Even though we spared some of amio’s gnarly side effects like dermatological, ocular, and thyroid toxicity, we still can see hepatotoxicity during the first 6 months of therapy – so liver function tests should be done, especially during these first 6 months.

Normal Sinus Rhythm Maintenance Misc: Disopyramide + Quinidine

Disopyramide: Also one of the agents that is not used for cardioversion, disopyramide is a sodium blocker that has both anticholinergic and negative inotropic effects and can be used for maintenance of NSR in patients with afib, and is used after electrical cardioversion to keep patients in NSR. Disopyramide is unique in that it has anticholinergic effects, and because of these effects, it can be useful in patients that experience their AFib during times of high vagal tone – like during sleep, coughing, straining etc. Because of its negative inotropic effects though, it should be avoided in those with structural heart disease. All in all, it isn’t used super commonly since there is a systematic review that suggests it may increase mortality slightly (along with quinidine).

Quinidine: One of the Na blockers (class 1 agents), quinidine also has K channel blocking effects at slower heart rates as well as vagolytic and alpha blocking properties. This drug is old and was one of the first used to ever treat AF. You don’t usually see it that often because, like disopyramide, has been associated with a slight increase in mortality. It can prolong the QT interval, can cause Torsades, and isn’t used frequently. The (one?) pro about quinidine is that it can be used even during advanced renal dysfunction. If starting your patient on quinidine, you’ll need close EKG monitoring d/t the risk of TdP. TLDR: quinidine is old, not used often, and if you’re using it, it’s probably because you can’t use any of the newer agents.

My patient is pursuing rhythm control but occasionally has infrequent spells of AFib. Do I give up or switch?

Nope! Often times patient symptoms may improve even without complete AF suppression. If you can get your patient from frequent, symptomatic bouts of AFib down to infrequent, well-tolerated bouts of AF – that’s a totally reasonable outcome – and does not necessarily mean you have to stop therapy.

If my drug requires EKG monitoring for initiation, when do I take the EKG?

Like discussed above, a lot of these antiarrhythmics are also proarrhythmic. Many of them carry with them a risk of QT prolongation and TdP (cough cough dofetilide and sotalol) and QRS prolongation (cough cough flecainide and propafenone). The optimal time to perform the EKG is when whatever drug you are using reaches peak drug concentration. So check the pharmacokinetics of your particular drug and go off of that.

When to do rhythm over rate control?

- Difficulty in achieving adequate rate control

- Younger patient age

- Symptomatic despite adequate rate control

- Tachycardia-mediated cardiomyopathy (aka ventricle goes boom boom too often and now your heart is enlarged and unhappy)

- First episode of AF/early AF (why? less structural damage)

- AF precipitated by an acute illness

- Patient preference

When definitely not to do rhythm control:

- When the patient’s afib has been deemed to be “permanent”. Don’t risk bad side effects for no reason, dawg.

- In patients with history of syncope, sinus bradycardia, PR interval prolongation (aka AV node issues), bundle branch blocks…we get a little bit more concerned with the risk of bradyarrhythmias with our agents

Big Takeaways for our Antiarrhythmics:

- Different agents exist for maintenance versus cardioversion.

- Cardioversion agents:

- Dronedarone, ibutilide, propafenone, amiodarone, and flecainide can all be used for pharmacological conversion of AF, provided contraindications to the select drug are absent.

- Amiodarone is an acute crummy cardioversion agent but can be good acutely for its rate controlling properties.

- Propafenone and flecainide can be given as “pill in pocket therapy” and are both class 1c agents.

- Do NOT use the pill in pocket therapies for patients with coronary artery disease and structural heart disease.

- Maintenance Meds

- Drug safety, not efficacy drives selection.

- Check out the below to help guide you in your selection (zoom in to see better)!