Hey hey, today we’re going to start talking vasopressors – we’ll start with an overview of the background material and then delve into our first pressor we’ll discuss: phenylephrine.

Let’s get into it already!

What is a vasopressor?

Vasopressors, also commonly referred to as pressors, are a group of meds that contract (tighten) blood vessels and help to raise blood pressure.

The pressors we will be talking about in these series include:

Phenylephrine (discussing today)

Norepinephrine

Epinephrine

Dopamine

Vasopressin

How does blood pressure work?

I would recommend a quick refresher of blood pressure and hemodynamics here, but just a friendly reminder that blood pressure has two main factors that affect it: blood volume and diameter of blood vessels (controlled by squeezing and relaxing).

I like to use a garden hose as an analogy.

Let’s say you have a standard rubber garden hose – no attachment at the end – and that house is attached to the spout. Let’s say you nudge that spout and turn it a little bit.

What does the water at the end of the hose look like? Probably just dribbling out a little at the end right?

But what happens if you let more water go through that hose? In other words, what happens when you open up that spout more and let it go at full speed?

More water, more pressure, and the further the water at the end of the hose will go.

Alright, alright: TLDR: our hose analogy has showed us that the more volume through the hose, the higher the pressure. The less volume the less pressure.

Now let’s say we leave that spout alone, keep it at a constant flow rate.

So volume will remain the same in this scenario. Now let’s move to the end of that hose. It’s definitely spitting out some water, but that water isn’t really going too too far. Just kind of leaves the hose and makes an arc as that water falls down to the ground. Like this cute lil kid on the right.

But what happens if we start to mess with the amount of space we let that water squeeze through?

What happens if we put our hand at the end of the hose and block 80% of the opening at the end of that hose?

That water is going to shoot way, way further than it did before. By restricting the amount of space the water had to flow through, you effectively increased the pressure of the water moving through that hose.

This is actually what garden hose attachments take advantage of. By forcing the water through a few tiny holes, the water that exists will have a much higher pressure and shoot much harder and go much farther. Who knew basic human hemodynamics was very similar to garden plumbing? (told ya cardiology is kinda cool).

The formula for blood pressure therefore includes fancily named variables representing blood volume and vessel size.

Blood Pressure = Cardiac Output x Systemic Vascular Resistance

aka

BP = CO x SVR

, where cardiac output represents circulating blood volume and SVR represents the squeeze of your blood vessels.

Cardiac output represents how much blood leaves the heart and goes to your body per unit of time. The formula for cardiac output is:

Cardiac Output = Stroke Volume x Heart Rate

, where stroke volume (SV) is the amount of blood the heart pumps out per beat. It’s important to incorporate both stroke volume and heart rate into the formula for CO, since even if your patients has a great stroke volume – but let’s say their heart rate is really low in the 30s – their heart isn’t getting enough blood out to those tissues right?

Tying it Together

To increase our blood pressure, our vasopressors all work on at least one (if not both) factors (SVR or HR) within our blood pressure formula. Having a good understanding of the basics of the these formulas above is key to understanding how pressors work.

The Sympathetic Nervous System versus the Parasympathetic Nervous System

Key to the idea of vasopressors is also getting an understanding of both the parasympathetic and sympathetic nervous system.

These are both involuntary (we don’t have conscious control over) nervous systems.

Let’s start with the sympathetic nervous system. The sympathetic nervous system goes a long way back. And I mean a long way. Thanks to this system, we weren’t eaten by dodos or sabertoothed tigers.

Let’s go back in time and use an example:

I am a cavewoman I have been working hard all day putting some cool lil sketches on the wall of my cave (afterall, I do love home decor) and I am out taking an afternoon stroll. All of a sudden, I hear a loud scream and it scares the absolute shit out of me.

What’s going to happen to my body? How are my vital signs going to change?

Several things are going to happen in my body at once.

My heart rate? Skyrockets.

My blood pressure is going to go up.

My pupils are going to dilate.

The hairs on my neck and body are going to stand on end, and I’m going to start sweating.

In other words, I’m going to feel a surge of adrenaline. That surge of adrenaline is the same thing you feel when someone pops up and scares you, or if you think you are missing the last step on the staircase. Or if your husband surprises you by bringing home Taco Bell (just me? hello?)

All of the above actions fall under the category of the sympathetic nervous system – also known as our “fight or flight response”. The things above are going to help me out in the case that I either have to fight whatever is screaming at me or need to run away as fast as I can.

My HR increasing is going to increase my cardiac output (right? since CO = HR X SV)

The rise in BP is going to help perfuse all my organs and get more blood to the tissues that need it, especially the working skeletal music.

My pupils dilating will help me see better by letting more light into my eye.

The sympathetic nervous system’s goal is really to prepare the body for strenuous physical activity.

So here I am, ready to fight this thing, when out it pops out of the bushes:

Phew. No need to fight or flight. In fact, I can relax.

Cue my rest and digest nervous system – aka my parasympathetic nervous system. The parasympathetic nervous system will slow your heart rate, increase blood flow to your intestines and stomach to help digestion. The parasympathetic nervous system is responsible for – what I like to call the itis (if you don’t know what that means, check it out on urbandictionary.com – it’s what I get s/p Taco Bell meal). The parasympathetic nervous is definitely not the star of our vasopressor talk today but just an FYI that it does in fact exist and it is a thing.

The neurotransmitters that run the show: our catecholamines

Now that we’ve talked a little about our two main types of nervous systems, let’s move on to some more specifics.

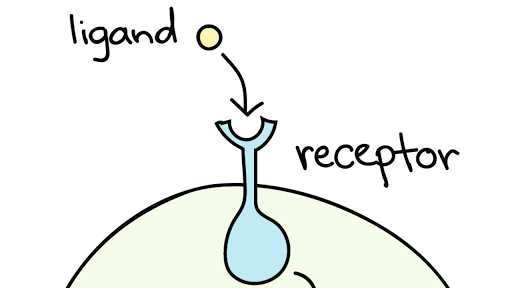

Our body regulates itself by using two main things: ligands and receptors.

Ligand is just a fancy name for a molecule that binds to a receptor. That molecule can be anything – hormones and neurotransmitters are examples of ligands that we produce endogenously (make it ourselves), whereas drugs are ligands that we give exogenously (from an outside source).

Receptors are located throughout our body – on every single type of tissue you can imagine. Receptors are all different chemically/structurally, so only certain ligands can bind to certain receptors. A receptor is just a molecule in a cell membrane that responds in a certain way to a ligand. In other words, when a ligand binds to a receptor, something is triggered/stimulated and something happens as a result.

Sometimes the analogy of a lock and key is used, where the lock is the receptor and the key is the ligand. Depending on the shape of the “key” (or the molecular ligand), it may or may not fit in that lock and cause something to happen. The whole basis of drug discovery is to synthesize molecules that can fit into (or BLOCK) these receptors to get effects that we want in our patients.

Many of the ligands (aka our vasopressor drugs) we will be talking about today – norepinephrine, epinephrine, dopamine, and vasopressin – are all synthesized endogenously (aka our body already naturally makes these chemicals) – so we weren’t really reinventing the wheel when we created them. But these drugs are literally lifesaving and are used every single day in the hospital (and some even are available over the counter to help with other stuff like a stuffy nose or a bleeding booty).

STUDY BREAK TIME. Go and take a biobreak, a 5 min stretch or walk. Tell someone ya love them. Over here at my household, we’ve been working on setting up my home office. She’s not ready yet, but part of the office is going to involve a freshwater aquarium. I’ve invested a ton of time researching the nitrogen cycle and all the cool stuff that needs to happen in your tank as the bacteria establishes itself before you can even put the fish in. So far we’re on week 2.5, and I’m about halfway through setting the happy bacteria up.

Back to it!

Receptor Overview

Our bodies have a variety of different receptors on their cell surfaces. A receptor is essentially a structure located on a cell surface that, when stimulated, performs an action.

There are literally like a bajillion types of receptors in our body, but today we’re going to focus on the key ones to understand in the world of pressors: today talking about the alpha receptors and beta receptors.

Alpha (α) Receptors

Medicine is pretty old school, so it’s not a surprise that some of the most important receptors in our bodies are named after Greek letters.

Alpha (α) receptors are key in the regulation of blood pressure. There are two main types of alpha receptors you should know: alpha 1 receptors (α1) and alpha 2 receptors (α2).

Alpha 1 receptors are found in vascular smooth muscle (aka the muscle inside of our blood vessels). When stimulated, alpha 1 receptors cause the smooth muscles in our blood vessels to contract. As those smooth muscles in the vessels contract, they will cause constriction of the vessel and cause the size of the vessel to narrow.

Test your knowledge: What do you think will happen to blood pressure when an alpha 1 receptor is stimulated?

Alpha 1 stimulation causes smooth muscle in the vessels to constrict, and decrease the size of the diameter of that vessel. As a result, the systemic vascular resistance will increase. By reducing the size of that vessel (just like when we reduced the size of that ending of the hose), we will cause an increase in blood pressure.

Conversely, if we block that alpha 1 receptor, we will see smooth muscle relaxation and vasodilation. This will cause a decrease in blood pressure.

Alpha 2 receptors are a little bit out of the scope of today’s talk, but they are found both in the brain and in the peripheral tissues. When stimulated, these alpha 2 receptors will decrease sympathetic outflow (aka decrease the fight or flight response) and lower blood pressure. Some drugs we may give to patients to treat their HIGH blood pressure include alpha-2 agonists (stimulators) like clonidine.

Alpha 2 can be a little tricky to remember in the beginning since stimulation of alpha 2 has the opposite effect of alpha 1 stimulation. Keep in mind that when alpha 1 is stimulated, you get a rise in BP, but when alpha 2 is stimulated, you get a decrease in blood pressure.

Beta (β) Receptors

Beta receptors are also part of the sympathetic nervous system (aka our “fight or flight” system); just like with our alpha receptors, the two primary subtypes to know for our pressor talk are beta 1 (β1) and beta 2 (β2).

The beta 1 receptor is located primarily in the heart. When the B1 receptor is stimulated, it increases contractility of the heart (inotropy) and increases heart rate. Think B for Beating.

Beta 2 receptors on the other hand are mostly associated with being the the smooth muscle of the lungs (bronchi). When stimulated, these bronchial muscles relax, and open up airways, making respiration easier.

Keep this in mind – this will come in handy as a way to remember a certain vasopressor later.

We love a good table to review:

| Receptor Name | Effects when stimulated |

| α1 | vasculature vasoconstriction |

| α2 | inhibition of neurotransmitter release (decrease of sympathetic tone) |

| β1 | increase heart rate and force of heart contraction |

| β2 | smooth muscle relaxation (e.g. bronchial/lungs) |

Let’s finally talk about the first star of the show: phenylephrine.

Phenylephrine

Phenylephrine is a direct acting sympathomimetic amine (aka it’s a molecule that we created that mimics catecholamines and stimulates part of the sympathetic nervous system).

Phenylephrine is one of the unique pressors because it only hits one type of receptor – the alpha 1 receptor. Think about your receptors we learned about above – what effect would stimulation of the alpha receptor have? Would it: increase blood pressure? Increase cardiac output? Increase heart rate?

By acting on the alpha receptors, phenylephrine causes blood vessels to constrict – which then decreases the diameter of your vessels (aka also increase systemic vascular resistance or SVR) and ultimately increases blood pressure.

By causing arterial vasoconstriction, phenylephrine increases afterload (don’t know what the heck I’m talking about? Check out this talk here).

Because phenylephrine only works as an alpha-1-agonist (stimulator), it has no direct effect on heart rate – it will not cause an increase in heart rate. In fact, you might actually see the opposite effect and see bradycardia or a slow heart rate. Can you think about why that may be?

Hint hint – remember your blood pressure formula!

Keep in mind that oftentimes, your body likes to compensate for abrupt changes.

Since BP = CO x SVR, and you are increasing SVR, your body might respond with a decrease in cardiac output, or CO.

If you remember – cardiac output is the amount of blood our heart pumps out per unit of time, or SV (stroke volume) x HR (heart rate).

Your heart isn’t great at abruptly changing stroke volume, but what it can do, is quickly change HR. To decrease cardiac output, your body will respond by a decrease in heart rate – bam, bradycardia – or more specifically, reflex bradycardia.

Formulations

Phenylephrine is given via IV continuous infusion with a bag or it is also available to give as a push dose via a stick (typical push dose ~50-200 mcg per push, repeat q 2-5 min).

Phenylephrine sticks should be very carefully monitored for a multitude of reasons. A big one is that a phenylephrine stick has a concentration of 100 mcg of phenylephrine per mL and is available in 10 mL or 5 mL.

So, how many total mcg are available in either syringe?

Well 100 mcg/1 mL = “X” mcg/5 mL; X = 500 mcg total (5 mL syringe); 1,000 mcg total (10 mL syringe).

So what happens if you have a patient get hypotensive (low blood pressure), and you push the whole thing into a patient? Woof.

That stick should be watched very carefully and used by someone who is familiar with its dosing, since it is very easy (and scary) to just pop in the whole thing – after all, it’s only 5 or 10 mL, and we often give 10 mL normal saline flushes like they are no big deal. Instead, doses like HALF A ML (0.5 mL) up to 2 mL (50-200 mcg) should be given every 1-5 min.

Also keep in mind that phenylephrine is fast on and fast off -it starts working within ~1 min and can last up to 20 min (but realistically we see it start to drop off after 5 min) so if you expect that your patient is going to stay hypotensive, you’re going to have a make a drip (aka a bag and start a continuous infusion) anyways; the push dose is just to hold them over.

Keep in mind that the perfect titratable drug to give via continuous infusion is one that is fast on/fast off. Fast on means that it will start working quickly – very much desired for our BP-crashing patients. Fast off – though it might sound bad because we don’t want the effects to go away “per-say” is actually also very desirable. This means you can quickly increase or decrease the rate of the drip/continuous infusion and not have to worry about things like accumulation.

| Formulation | Dosing | Stuff to know |

| IV continuous infusion (phenylephrine) | Initial Rate: 0.5 – 2 mcg/kg/min Usual range: 0.25 – 5 mcg/kg/min Max dose: ~9-10 mcg/kg/min | Also can do non-weight based dosing, though weight based seems to be the most prevalent |

| IV push/phenyl stick (phenylephrine) | 50 mcg – 200 mcg bolus over 20-30 seconds | Usually available in 10 mL syringe (conc 100 mcg/mL) – do not push whole stick (!) |

When to Use:

Every patient is different, but in general – we like to use phenylephrine when your patient has hypotension with tachycardia – since it does not increase HR like a lot of our other pressors can. We also like to use phenylephrine in patients with normal cardiac function (since it doesn’t add any support because it doesn’t hit beta-1).

It can be used in things like refractory afib with rapid ventricular rate (RVR), or in septic shock, neurogenic shock, and hemorrhagic shock – assuming that you’ve first replenished volume in the vessels first if needed. (Keep in mind – if your patient is bleeding out to death – you can squeeze and clamp down those vessels all you want – but without enough volume, you won’t get a good enough BP/perfusion). It can also be used in intra-op hypotension and hypotension seen with anesthesia.

It’s not the most commonly used pressor (even in the indications above), but it definitely has its place.

Question (for those who have reviewed the heart failure section already): Is phenylephrine a good pressor choice in those with systolic heart failure? Why or why not?

Phenylephrine is definitely not the pressor of choice in systolic heart failure. Keep in mind in this condition you already have a weak, tired, left ventricle. Yes, he contracts and tries, but he’s super super weak and can’t generate a large force of contraction to PUSSSSSHHHH that blood out. The last thing we’d want to do in this patient is add on an agent that solely increases afterload. By increasing the pressure in the arteries and increasing the amount of pressure that LV now has to push against, that’s like saying “hey I know you’re really weak and tired but can you actually push harder?”

The same is true in cases of severe pulmonary hypertension – something we haven’t discussed yet – avoid phenylephrine in these patients.

Key Side Effects:

- Reflex bradycardia, like we discussed above.

- High blood pressure (aka hypertension). Obviously one of the reasons we are using it as a pressor, but may not be wanted if we are using it for a different indication. This is a potential side effect of any pressor that also hits alpha-1 receptors.

- Anxiety, headache, restlessness, insomnia, excitability (hi, it me). Not surprising given that phenylephrine is a synthesized catecholamine. This is a potential side effect of any pressor that also hits alpha-1 receptors.

- Ischemia (aka inadequate blood supply) which can lead to tissue death if not fixed. This is pretty much true of any pressor that works on alpha-1 receptors. Besides vasoconstricting our large arteries, they also vasoconstrict smaller vessels like those in our fingers, toes, blood vessels feeding the gut, etc. The vasoconstriction of these smaller vessels leads to an overall decreased blood flow to the tissue they support, so we can see things like gut ischemia, digital (finger) ischemia with long term or high dose vasopressors. In medicine though, everything is, of course, risk versus benefit, and phenylephrine is one of our life saving medications. This is a potential side effect of any pressor that also hits alpha-1 receptors.

- Tissue necrosis if phenylephrine infiltrates your peripheral line (aka the medication starts leaking out of the vein/vessel at the injection site). This is why we give all of our pressors through central lines, which are stronger and terminate in a large vein causing rapid and good dilution of the drug. However, you never want to delay pressor administration due to lack of a central line. This is a potential side effect of any pressor that also hits alpha-1 receptors. If you do see infiltration, phentolamine can be used as a treatment. Phentolamine is an alpha receptor antagonist so it can counteract the effects of phenylephrine. You can dilute 5-10 mg in 10-20 mL NS and administer to the site of extravasation and repeat PRN.

A key thing I wanted to quickly mention: cardiac arrhythmias are not common with phenylephrine. This is because phenylephrine does not hit the beta-1 receptor. This is not true of some other pressors we will eventually talk about!

FYI: Other uses

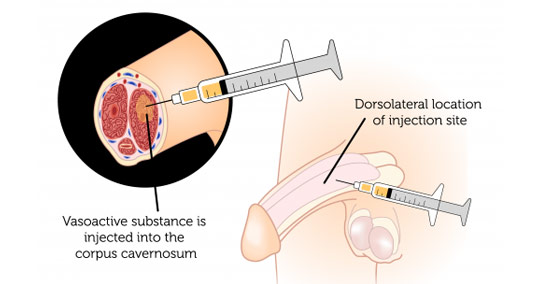

Because of its effects on constricting blood vessels, phenylephrine can also be used more locally (not systemically) to treat other conditions such as hemorrhoids (caused by dilated/swollen veins in the rectum), as a nasal spray decongestant (constricts blood vessels in the nose, to treat intraocular bleeding, and to treat priapism (which is when the penis remains erect for hours – super dangerous since the blood that remains in that penis is sitting there and starts getting deprived of oxygen). We literally inject (with a needle) phenylephrine right into the penis (in an area called the corpus cavernosum) to help restrict those blood vessels and decrease blood flow into the penis. I’ll never forget when I was a resident and I heard an unlucky patient go through this procedure. Terrible, but better than the alternative which is possibly losing some or all of your penis due to tissue death.

Fun fact for my pharmacy-interested friends: trazodone (or “trazobone” as we say in the business) is a possible cause of priapism.

Fun fact – if phenylephrine can be used to stop erections, what do you think can be given orally to help patients get an erection? *hint: we’ve already talked about it today briefly*

[ insert thinking pause here ]

Phentolamine – our alpha antagonist.

It can also be used locally in the eye (via drops) where it constricts the dilator muscle causing dilation of the pupil – making fundoscopic exams possible.

Stay tuned for more fun, less priapism-related pressor talk in future posts! Stay cool.