Happy September everyone! As a northeast coaster, I am definitely looking forward to this fall and the cooler weather. I am indeed a basic bitch when it comes to the autumn (guilty as charged). I have been living for my morning pumpkin cream cold brew.

Today is part 2 of our VTE series which will focus on the presentation and diagnosis of DVT and PE.

If you haven’t checked out part 1, I would definitely recommend giving that a once-over before reading today’s post.

Alright, without further ado, let’s get into it!

Part 1: Deep Vein Thrombosis (DVT)

Presentation

So, from part 1, we already know that a DVT is when a clot (aka thrombus) forms in the vasculature of the deep veins.

When a patient presents with a DVT, they commonly report some hallmark symptoms. These include pain, swelling, and redness at the site.

Well, – we already talked about heart failure, and you also said lower extremity swelling is a hallmark symptom of that – so, how can I tell if it’s a DVT or just run-of-the-mill stable heart failure?

The biggest differentiator is whether the swelling unilateral (occurring on only one side) or if it is bilateral (happening on both sides).

The chances that your patient has an acute clot/DVT in both their lower extremities at the same time is very low (but not impossible).

Generally, DVT s/sxs (signs and symptoms) occur unilaterally, whereas heart failure swelling is bilateral. You can check out the differences between a patient’s legs with an acute DVT in the pic below – you can see the classic swelling and redness immediately.

👏Location, 👏Location, 👏Location

Just like the most important rule of real estate, location is also important to consider when treating a DVT (or should I say, deciding whether or not to treat a DVT – but we will get there eventually).

I am getting seriously bad flashbacks from the long journey of buying my first house about a year ago in this market in NJ *shudders*.

The majority of DVTs occur in the lower extremities….and when I say the majority, I really mean the majority.

Upper extremity DVTs are rarer, and most of them are actually due to iatrogenic (meaning we caused them as healthcare providers) reasons. With that being said, a lot of upper extremity DVTs happen in the hospital.

Can you think about why a patient in the hospital might get an upper extremity DVT?

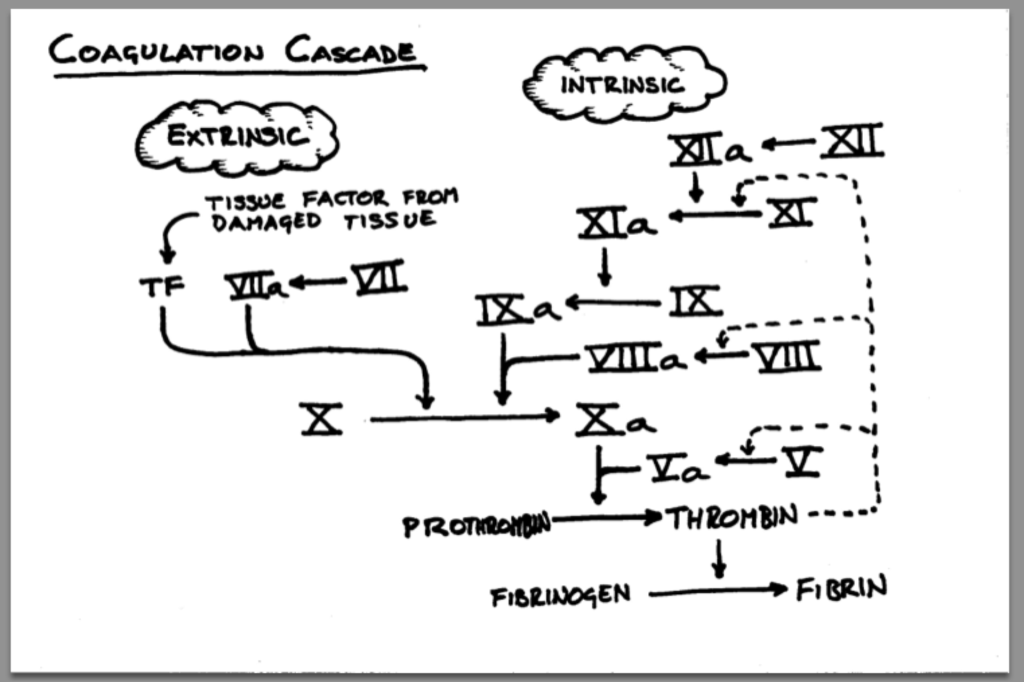

It’s because we’re sticking so much stuff into em! Any IV line, cath, etc is a potential site for a VTE to happen. That’s because not only are we breaking open part of the vessel during insertion (aka triggering that extrinsic coag cascade) but we also have a foreign object in the vessel (cue the intrinsic coag cascade). Both have the potential to trigger the clotting process.

An ✨essential✨ thing to assess when you’re discussing a DVT event is where the heck the clot occured.

We have a bunch of veins, but not all of them are equally “important”.

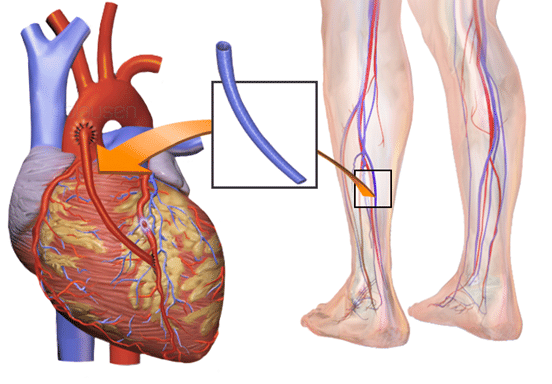

In fact, we don’t even really need all of our veins. If you remember in our ACS talk, we discussed what happens in CABG or coronary artery bypass grafting. The surgeon will actually remove (the proper word for this is HARVEST but idk why but that literally gives me a lil of the heebie jeebies) a vein from the leg to use as a new vessel to connect in the heart/aorta.

Additionally, not every vein has the same risk of a clot lodged there to embolize and go to the lungs. This is a big factor that is going to drive differences in treatments (or lack thereof).

As we discussed in our previous post, a big complication of DVTs is that a part (if not all) of that clot breaking off in that vein, traveling up through our inferior vena cava, into that right heart, out of the RV and *pop* right into that pulmonary vasculature. And thus, DVT -> PE.

Rule of thumb: as the name would suggest, we are talking about the deep veins here. DVTs are the clots that carry that high risk of embolization.

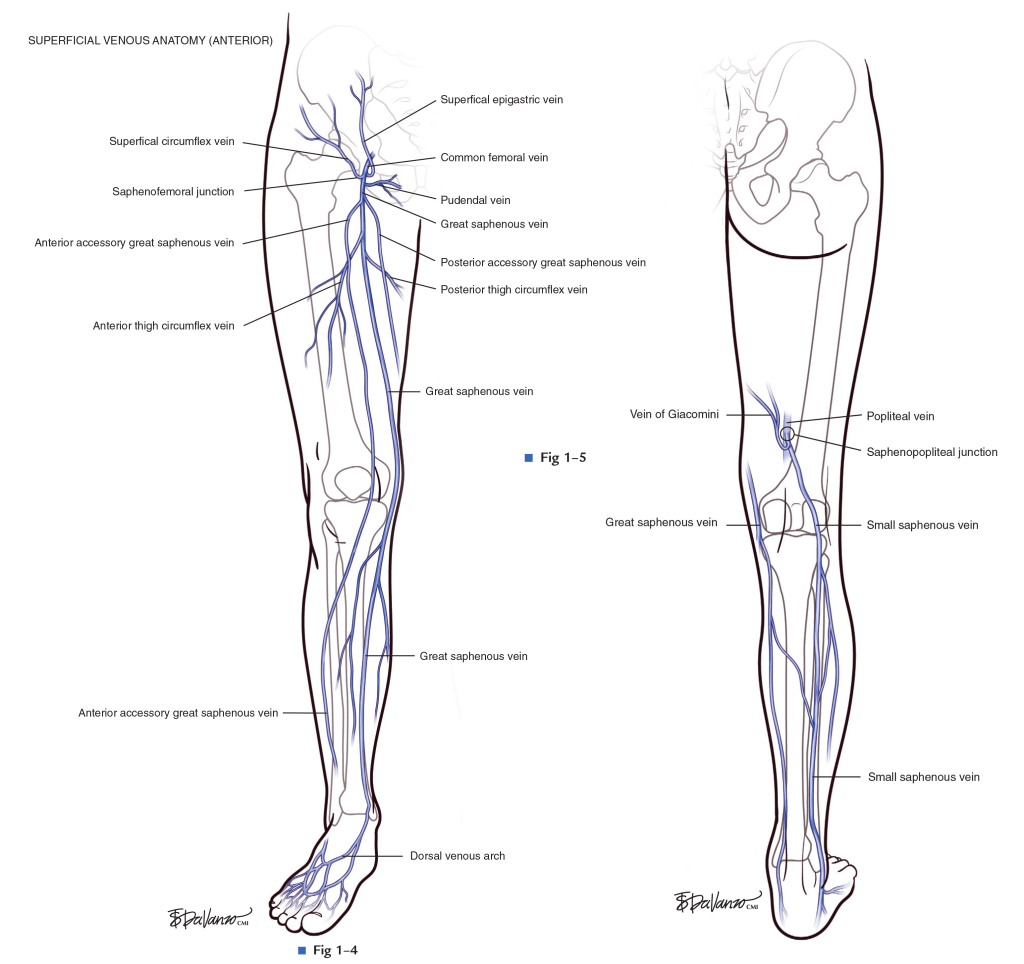

In our body we also have what is called “superficial” veins (they’re so vain….get it?!). These are smaller and have less chance of embolizing. In fact, if a clot forms in a superficial vein, often the risk of anticoagulation does not outweigh the benefit of treating that clot. We will dive into this more later during our treatment talk.

There’s also a breakdown between what we call proximal DVTs and distal DVTs.

Distal deep veins are found in the calves and include the anterior tibial, posterior tibial, and peroneal vein.

The proximal veins include the external iliac, deep femoral, and popliteal veins.

Proximal DVTs (aka the ones closer to the trunk of the body – aka the ones in your thighs versus the ones in your calves) tend to be more clinically important because they are more commonly associated with embolizing/breaking off and taking the fast lane to the lungs where they can cause a pulmonary embolism.

This doesn’t mean that we don’t treat distal DVTs. Distal DVTs should be treated if any of the following is met:

- your patient has symptoms

- if the DVT has grown/extended

- if there is high risk for extension of the clot (e.g. high d-dimer >500, prolonged immobility, extensive thrombosis in multiple veins, unprovoked DVT, prior hx of clots, etc)

If you happen to find a distal DVT by chance (aka your patient had no symptoms and no risk factors for extension), you can actually hold off treating that bad boi and should just get serial imaging (1 image q week) for 2 weeks. As long as that bad boi doesn’t extend on serial imaging over time, no anticoagulation is the way to go. However, if it starts to extend, especially into the proximal veins, that lil’ DVT just bought a ticket for AC.

Superficial Vein Thrombosis (SVT)

You also have a series of blood vessels in your body known as superficial veins. SVTs generally affect the lower limbs, with about 2/3rds of lower-limb SVTs occuring in the saphenous vein. It is not uncommon to find a SVTs at the same time as a DVT – they often can occur together.

Every time you have a patient develop a new clot, I’d recommend actually reading out the report and seeing in which vessel did this clot occur. If it’s exclusively in a superficial vein, most of the time, we’re going to d/c that anticoagulation unless they are at increased risk of clot progression to DVT or PE.

This intervention is simple but may prevent patients from being on anticoagulation where its not needed.

At the end of the day, the decision to tx (or not to tx) is really dependent on risk versus benefit. We will go into more details in the treatment section.

Diagnosis of DVT

There’s a bunch of different components involved to diagnose a DVT. Patients present with all kinds of symptoms all the time, like lower extremity swelling – does that mean we should get tests and run imaging on every patient that presents with lower extremity swelling?

Probably not (and by probably I mean definitely). That would not only cost the healthcare system a ton of money, but also a ton of time. And then those machines also wouldn’t be as available for people that really need it.

So how do we figure out who to test and who to not test?

For this, we use a ‘scoring system‘ which basically gives you an idea of their “pretest probability” that they are having an active clot.

One scoring system that is commonly used is called the Wells’ criteria. The Wells’ criteria takes a bunch of risk factors into account and spits out what your patient’s likelihood of having a DVT is. You can check it out below:

If the score is low enough, your patient has a low probability, and other etiologies should be considered. But if it’s high enough, you’ll want to pursue a potential DVT diagnosis.

What about some labs? There is a lab, known as D-dimer that we can test for. But what is d-dimer?

D-dimer is a degradation product of cross linked fibrin and also a marker of inflammation. Keep in mind that your body has mechanisms to break down an existing clot, just like it has mechanisms to form a clot. If you have a clot, your body is able to naturally break down existing clot, break down that fibrin, and increase d-dimer levels as a result.

When you think about it, we are really relying on your body’s natural ability to break down an existing clot in medicine very often. Every time you give anticoagulation to a patient with a clot, keep in mind you are doing nothing to existing clot. You’re just preventing more clot from forming. Giving anticoagulation really depends on your body’s ability to break down clot for treatment to work.

D-dimer is also…..imperfect.

A rule of thumb is that the d-dimer is good for ruling out DVTs (in other words, if your d-dimer is negative it is a good indicator that there might not be a clot) – but if your D-dimer is positive…. it does not always mean your patient has a clot. Many, many, many factors can contribute to high d-dimers outside of the VTE world (some include age, cancer, etc).

So now you have your d-dimer, your wells score. Everything is pointing to a possible VTE. These two by themselves are not enough to diagnose a DVT, they are more of screening devices we use to figure out who to actually test.

Next we get imaging to definitively diagnose. Methods include 🌟compression ultrasonography🌟 (aka a 🌟Doppler🌟) or venography.

What is a Doppler?

Ok, bear with me. Do you remember the term the “Doppler effect” somewhere in the far reaching corners of your brain? Like the part of your brain with the cobwebs that contain other stuff like knowing what the ancient Mesopotamians ate and did.

The doppler effect is the name of the phenomenon that occurs when a moving object producing sound moves by a stationary object.

The classic example of the doppler effect is an ambulance passing by. As the ambulance passes by, the frequency or pitch of the sirens changes from a constant high frequency to a constant low frequency, even though the technical frequency has remained the same.

A Doppler ultrasound utilizes the same principle. The doppler ultrasound is a non-invasive imaging test that uses sound waves to detect blood flow in vessels. By spitting out sound waves that are reflected from moving objects (aka your red blood cells), a sonographer can detect interruptions in flow (aka clots). These bounced-off sound waves then are translated back into the computer to create an image. So, ultrasound indeed is ultra-sound. 🤯🤯🤯🤯

Ultrasound is truly mind-blowing and magical when you find out how it works.

If you want to learn more about US and how it works, I highly recommend this layperson-friendly podcast episode from Stuff You Should Know (one of my favorite podcasts – besides true crime/murder ones).

Doppler US is awesome because it is: quick, painless, noninvasive (and magical as you’ll learn). Doppler is usually considered the 🌟gold standard🌟 imaging to diagnose a DVT because it is non-invasive and quick. However, in certain patients, such as morbidly obese patients, Doppler may not be effective at getting a clear picture.

What is venography?

Venography is a more invasive technique that involves injecting a radiopaque contrast dye (aka a colored dye that will appear during X-ray) into your vessels and then taking serial X-rays. The dye has to be injected via catheter (flexible tube) at a certain site depending on where the clot might be so the doc will typically assess through the femoral vein in the groin and snake the catheter to the appropriate location before injecting the dye. The dye will light up in your patient’s vessels like a Christmas tree to help visualize blood flow (or clots).

Part 2: Pulmonary Embolism

Presentation

Ok so you got a clot in your lower extremity veins, and a pesky little piece of that clot breaks off (aka embolized into your lungs). Not great.

We already talked in part 1 about how these patients can present very, very severely….I mean, they can even present in a code blue – I’m talking full on cardiac arrest. If you remember that’s due to their RV basically crushing their LV and getting overstrained.

So yes, these patients can present mid-CPR to the ED, or even unfortunately not make it to the ED.

There are all kinds of PEs (as we will soon discuss), and some can present more milder than others. Common s/sxs include tachycardia (fast heart beat), dizziness, sweating, fever, sudden severe shortness of breath, leg pain/swelling (because often they have a concomitant DVT), and chest pain.

Patients can also have no symptoms at all. What a wild world. So you can either be asymptomatic or you can be dead.

Categories

PEs are broadly broken down into 3 categories based on severity: massive, submassive, and nonmassive.

Listen, I didn’t name these categories but I low-key hate how they sound together. The massive and submassive is ok, but idk why but I hate the nonmassive part. It’s the worst when I’m teaching new students and they all sound alike.

Let’s start with the worst kind: massive.

The major defining feature of a massive PE is systemic hypotension. Although hemodynamically unstable PE is often caused by large clots, the hallmark is the hypotension, and so the term “massive” PE doesn’t necessarily have to do with the size of the clot, but rather with the hemodynamic effects it causes.

As we talked about in part 1, this causes severe cardiopulmonary failure because that RV gets overloaded, pushes on that LV (aka septal bowing happens) and bam – decrease in cardiac output and since BP = CO x SVR -> systemic hypotension.

As you might have figured, this condition has the highest mortality rate (and the mortality is pretty high – anywhere from 25% to a whopping 65%).

These patients will have sustained hypotension (aka <90 mm Hg systolic or a drop in systolic arterial pressure of at least 40 mm Hg) for >15 min. RV strain can be seen on ECHO like in the pic below:

A submassive PE is when your patient is still hemodynamically stable, but are already showing some RV dysfunction or hypokinesis (not contracting as hard/moving as well as it should).

A nonmassive PE is the friendliest of all PEs. Your patient does not have any evidence of RV dysfunction on ECHO and are hemodynamically stable. These patients may have symptoms or may even be asymptomatic.

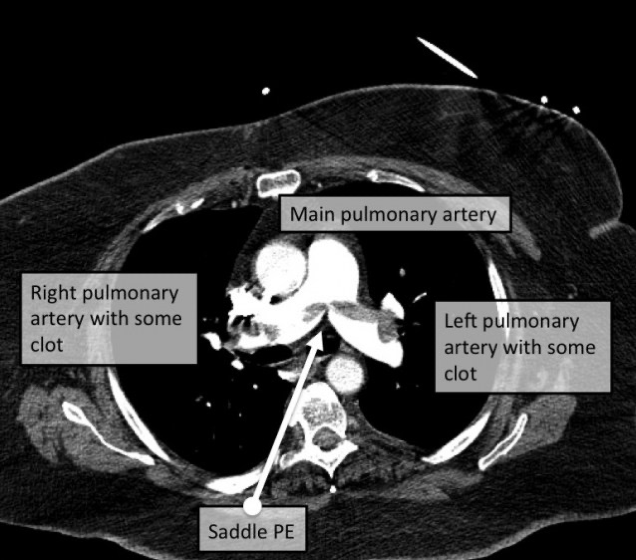

You can also break down PEs based on their location. Going from the biggest -> smallest, you have saddle PEs, lobar PEs, segmental PEs, and subsegmental PEs.

Saddle PEs are oftentimes the most severe, since the clot gets lodged before your lung vasculature branches off (the fancy way is saying it occures at the bifurcation of the main pulmonary artery), thus blocks blood flow to both sides of the lungs.

Diagnosis

The diagnosis of PE is somewhat similar to that of DVT in that you again start with a pretest probability scoring system. In other words – a lot of people present with shortness of breath – a lot of people present with chest pain. Are we going to test everyone for an acute PE? Yeah, no.

Just like our DVT diagnosis, PEs also have their own Wells Scoring System for patients with suspected PE in the ED. You can check it out below:

Labs also include a d-dimer, and unlike DVTs, you can also get cardiac troponins (which we talked about in our ACS posts) – if the PE is bad enough, it will cause cardiac strain and you’ll get that troponin bump.

Unlike a Doppler, though, PE has its own type of imaging to assess.

These include ⭐ chest CT⭐ (aka computer tomographic pulmonary angiography – try to say that 5 times fast) and also ECHOs (like I alluded to above).

Chest CT is the ⭐ gold standard⭐ because it is more specific in that it is excellent at detecting insufficient filling and/or clot. Chest CT is so great these days, that incidental PEs are sometimes found (AKA you had a clot and didn’t even know and had no symptoms but we found it by accident).

A chest CT utilizes radiation and is an imaging modality that is able to take very very very thinly sliced pictures of the chest. Oftentimes patients will also get special contrast agents intravenously. This contrast dye will go into your chest vasculature and light up on the CT scans, making it even easier to see issues like clots.

Since we are talking some radiation – fun fact: Marie Curie was actually Polish not French as a lot of people suspect by her name. She was born Maria Skłodowska and not only termed the word radioactivity but also discovered two elements – radium and polonium (named after Poland, the place of her place of birth). Both Marie and her older daughter died of radiation exposure (her older daughter died at 58), but her younger daughter lived until 102! Both my parents are from Poland, so you better believe we visited her museum the last time I was there:

Alright, alright now ECHOs – or echocardiogram. An ECHO can help you visualize more of the heart’s structure and function – and see how it moves. This is where you can detect septal bowing and RV strain. In fact, ECHO also uses ultrasound just like our dopplers do!

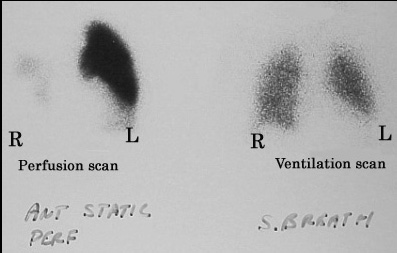

Lastly, not as common, but there is something called a VQ scan aka a ventilation (the V) – perfusion (the Q) scan. How does this work?

Think back to how your lungs work. Keep in mind that your lungs need both good perfusion and good ventilation to work.

In a health patient, air enters the lungs and going into our little tiny air sacs called alveoli. The alveoli puff up with good oxygen/air and are covered in capillaries. Our capillaries are able to take the oxygen and good stuff out of the alveoli and trade it for some bad stuff like carbon dioxide that we then breathe out.

In other words, you have to make sure your alveoli are nice and open and are able to take it good air/oxygen. If you have alveolar damage, an empyema (a cavity full of pus in your lungs), or other things going on, your alveoli will not be able to fill nicely with air. No matter how perfect your capillary blood flow to those alveoli is, it will still not be able to get good exchange because there is a problem with your alveoli/ventilation.

Visa versa – if you had great alveolar filling but terrible blood flow (aka bad perfusion) in those capillaries like…in a PE…you still won’t be able to get good exchange. In this case, your ventilation would look good but your perfusion would be crap.

This is what the VQ scan tests for. First your patient will breathe in some nice radioactive material (we call this a tracer) and X-rays will be taken. Next, they will inject a lil radioactive stuff into your patients vein and take an X-ray to detect blood flow.

In a healthy patient, there should be a “matching” good perfusion and ventilation. However, if patients have a PE, their perfusion will be decreased.

Thanks for hanging around today. Stick around for the next post on treatments! Until then, enjoy the fall season.