Today we are going to be talking about some general stats stuff. For all my stats posts, I will always preface with the understanding that YA GIRL is NOT a statistician. At all. Seriously. I envy the brilliance of those people every time that time comes around during research.

With that being said though, I had no idea what was happening in stats when I was in school. To be honest, I didn’t really understand a lot of drug lit stuff until the tail end of PGY2 year but really when I finally had some time to sit down with this stuff and be like wtf am I actually looking at here and what does it mean?

Today we are going to have a lil talk on internal validity, external validity, and run-in periods. These are all fancy terms that I didn’t really get at the time but hopefully you might understand them a little bit better after this post.

✨✨✨These topics today are all things you should consider when reading/interpreting/presenting a journal club.✨✨✨

Without further ado:

Running a trial and what to do with the data

Let’s rewind back to school-version me.

I used to think that trials were like super medical and very factual and very black and white. I didn’t realize understand that there’s about a million different ways to look at, and present, the same amount of data. When I did a journal club, I was like a lil parrot reciting everything that the trial did, and what they found. And I had no idea what it really meant.

This is my ploy to make you smarter than school-version of me. Do better than school version of me.

Ok: Let’s start with two ways to assess data. There’s two major ways to slice up your data and to analyze it. You can either use an intention-to-treat analysis or you can use a per-protocol analysis.

Intention to Treat (ITT)

Luckily for us, even though these names are kinda fancy-sounding, they still make sense if you think about what they are saying.

In intention to treat analysis, you start off by separating and randomizing patients into your groups like normal.

Let’s say we are assessing two drugs against each other: Drug A versus Drug B. (original, ikr)

We’re about to start the trial.

Let’s say you get assigned to take drug A and I get assigned to take drug B. Now, you guys know by now I’m visual, so figured I’d make a graphic to illustrate this clearer.

We’re in our groups – let’s say the trial goes on for a total of 3 months, and then the data is pooled and looked at.

Intention to treat is exactly what it sounds like. As an investigator, I intended for you to be in the drug A group and I intended for me to be in the Drug B group.

So – no matter what happens after that initial assignment – your data will be included with the Drug A group, and mine will go with the Drug B group.

👏👏👏Let 👏 that 👏 sink 👏 in 👏👏👏

Let’s put this in other words. Even if you skipped a bunch of drug A doses, or never took drug A OR ended up saying screw that and took drug B instead ….. your results will still be grouped with Drug A.

Now, you might be asking yourself – why the heck would a trial do this?

There’s a couple of good reasons. By allowing patients to kinda do what they like, you are better mimicking what will happen in the real world.

Are humans perfect IRL? Def not.

Real world really does mean that your patient might skip a dose, and not perfectly take your drug. But….. because of this loosey goosey allowances, you aren’t capturing the 100% true effect of the drug, since not everyone is taking it exactly as they should be prescribed.

We have these terms in lit called internal validity and external validity. The way I remember what they mean is I always think of internal validity as living within a bubble of a trial. And visa versa, external validity is outside of this utopian trial world – aka what happens IRL.

What do you think ITT analyses would have? High internal or high external validity?

Well, because we are kinda allowing patients to do what they would normally do, ITT trials have higher external validity because they better mimic real life.

The benefits of ITT

You might be asking yourself – I still don’t really get why someone would do ITT – and I think it can be best solidified by an example.

Let’s say you have a drug to treat hypertension and let’s say it’s FANTASTIC. It is really quite effective. Bravo. This is amazing, we did it! We saved the world of resistant HTN.

Eh, well. Not so fast.

Well…..let’s say this drug actually frequently causes explosive diarrhea. Like…. in a lot of patients.

If you only conducted a per-protocol trial (which we will discuss soon), you will see ALL the benefits of how effective this drug is at lowering BP, but really not see some of the true effects of the drug IRL – which is – in reality, that not many patients will take it and many discontinue it on their own.

ITT can still capture these patients.

What to look for with ITT?

Kinda like I hinted above, whenever you have a ITT trial, you should always check out if they report things like crossover rate or discontinuation rate.

This could totally skew how you regard your results. Classic example I like to use is the AFFIRM Trial.

The AFFIRM trial was a 2002 study that looked at what the heck was better for treating patients with a fib – rate or rhythm control? This was an age old question and it was time to finally get the answers.

If you first glance at the trial, you’ll find that in these patients, there was no survival benefit found between rate or rhythm control – aka they were both equal – but you did see the rhythm control group trend towards increased mortality (that means it was a numerical difference but no stat significant difference).

It’s easy to look at this trial, read the results, call it a day, and go binge Wednesday on Netflix. But if you look into the analysis of the trial, you will see that it was a intention-to-treat analysis.

Next, if you check out how many patients crossed over (aka switched from rate to rhythm or switched from rhythm to rate), you’ll see that there was a statistically significantly higher rate of crossover in the rhythm control group with a WHOPPING 37.5% crossing over. In other words, almost 40% of patients that were analyzed as being in the “rhythm control” arm were actually taking rate control agents instead.

All of a sudden the results aren’t so black and white, huh? Kinda hard to really be able to compare these drugs for sure, knowing that more than a third of my patients assigned to rhythm control really ended up taking rate control agents.

What this does tell us? Well I think a few things. Rhythm control drugs are likely much less tolerated (which we do see in practice). This is really shown in this trial.

But if you really ask me based on this trial if both strategies are similar? Well, I would say this data is not convincing due to the extremely high rate of crossover. This would be a big con of the trial when presenting these conclusions (imo, of course).

Per Protocol

Next up we have per protocol analysis. And – once again – it’s exactly what it kinda sounds like. I’m makin’ my trial, coming up with a protocol that you need to follow, and guess what – if you don’t follow it – even if you miss one or two doses – you are OUT – aka we are not including you at all in our data.

IT’S MY TRIAL AND MY RULES OK.

So back to our example – you’re allocated to Drug A, me to Drug B – if we’re using per protocol analysis, we will only be included in the data if you stuck to the script and took drug A and I only took drug B. Aka stuck to our assigned groups.

Knowing the above – would PP analysis have high external validity or high internal validity?

It would have high internal validity. Afterall you are in that perfectly scripted, take-every-dose, utopian trial bubble. This is good because it really tells you the true effect of the drug, On the other hand though, it might not really capture the true tolerance of the drug or the effects it would have in a “real world population”.

What to look for with Per Protocol?

Whenever you see that a trial conducted a per protocol analysis, check out if they report how many patients ended up being excluded from data and why. Good trials will list out example what percentage of patients were excluded, and great trials will tell you for what reason. This can help provide insight about the tolerability of the drug and other effects it might have.

Modified Intention to Treat

Another thing to note (and again, not something I realized when I was in school) is that trials can do whatever the heck they want as long as they explain/report/define what they’re doing.

Because of this, trials can totally decide to analyze data based on a modified intention to treat, or mITT. What does that mean?

Literally anything! The investigators generally get to choose how they define this.

The can define it, for example, as “we will include you as long as you received the correct drug for the first “X” number of days”.

Whenever you see an mITT, make sure you understand how it is defined and how that might change interpretation of results.

Run-In Periods

Ah yes. Another term I threw around in school knowingly but had no clue. Let’s talk about what a run-in period actually is.

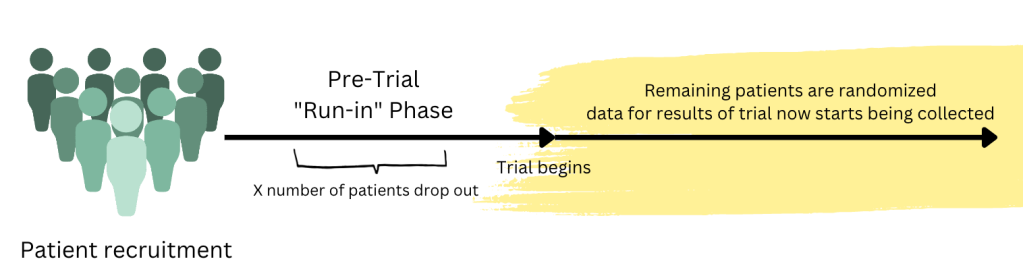

A run in period is a period of time between the actual recruitment of the trial to when the trial actually starts where all participants get the same treatment.

The data you are trying to capture in your trial (for example, mortality difference) isn’t actually being recorded during the run-in period. This is like a pre-trial period.

Hopefully the graphic I made above kinda illustrates it better. If you were to do a trial, first you have to get a group of people who are going to participate in the trial. Then you put them through an investigator defined “run-in” phase. During this phase, the data that is being collected/what happens to these patients is not included in the results of the actual trial.

During the run-in phase, you are going to have a certain number of patients drop out for various reasons. Once this phase is over, now you can finally start the trial. You will take all these remaining patients, randomized them into different groups (e.g. Drug A vs Drug B) and now the data for the trial will start being collected for the results.

Why do a “run-in” period?

There’s quite a lot of reasons a trial might decide to incorporate a run-in period, some sneakier than others.

A common reason for a run-in period is using it as a sort of “washout period”. For example, hypothetically let’s say we wanted to see the true effect of an anti-HTN medication. Well a ton of patients in that trial might already be on all different kinds of doses of all different kind of anti-HTN drugs, so in order to make sure the effect is from the drug itself and not a residual effect from another drug, you could incorporate a run-in period to ensure that all patients are starting at a true “baseline”.

Or let’s say they might be on other drugs that interact with the drug you are testing. Classic example is patients on an ACE-I – they need a 36 hour period of washout prior to starting an ARNI due to risks of angioedema and whatnot. A run-in period might require that everyone who was previously on an ACE-I stop these drugs so they can safely start the trial.

A trickier kind of run-in period is one that can be for “safety and tolerability”.

You might be asking – what’s tricky about that?

Well, your results and your interpretation of said results might become skewed. Let’s say we are trying to give patients a new drug, and we have a run-in period where we declare that in order to be randomized/start the trial, all patients must be able to tolerate a drug at a certain dose. Oftentimes they will have an uptitration scheme (e.g. week 1 of run-in period you get 5mg, week 2 10 mg, etc).

And along the way, a bunch of patients are having to drop out, because they don’t tolerate the drug they’ve been getting or have unacceptable side effects.

These patients aren’t being represented in the results of that trial. So in other words, often “run-in” periods can be a sly way for investigators to get a cream-of-the-crop, hearty, more likely tolerate/have less side effects patients when they are starting their actual trial. Because of this, noted “side effects” or ADRs or discontinuation rates may be a lot more common in practice compared to life within this trial.

Putting it into Practice with an example!

I’m a very hands-on learner. Can’t just sit there and read all day. Let’s test your knowledge with a real life example.

We are going to discuss the PARADIGM-HF trial. This is the landmark trial that got sacubitril/valsartan (aka Entresto) FDA-approved for the treatment of patients with systolic HF (HFrEF).

I want you to skim over this trial. What kind of analysis was there? What does this tell you? Did they have a run in period? How might this skew results? What might analyzing this trial tell you about real-world use of Entresto?

I’m serious.

Seriously, go check out the trial!

Answers below (! spoiler alert)!

What kind of analysis did they use? They used an intention to treat analysis. This means that the trial has the potential to have more real-world applicability.

Because I see the term “ITT”, I’m going to see if they reported crossover rates. Don’t see this reported, but they do report that 17-20% of patients discontinued the drug during the trial which is interesting. The good news is, this # was decently similar between groups so should balance out.

Did they have a run in period?

Yep, looks like they did. In order to start the trial, you had to complete a run-in period. They report it as a single-blind run in period, where all patients had to receive and tolerate enalapril 10 mg PO BID x2 weeks then the ARNI at 100 mg PO BID then 200 mg PO BID for 4-6 weeks.

All patients with significant side effects did not continue onto the trial.

Couple of things to unpack here.

School-version me would be like OK cool this is what they did.

But what does this actually mean, clinically?

To understand that better, first we should assess – are they high doses? Low doses? What?

Well, these are pretty hefty doses of drug. Starting dose of enalapril is 2.5 mg PO BID, and 10 mg PO BID is really a full, basically target dose of this drug. Then these patients had to tolerate high doses of the test drug too in order to be randomized.

Next you should consider what “side effects” patients might have experienced on an ARNI or ACE-I. Immediately things like hypotension, hyperkalemia, dizziness, AKI come to mind.

Now, the PARADIGM HF is a robust trial, so they did good work and made sure to report out how many patients were kicked out during run-in and for what reason. What you end up seeing is 19.8% of patients that were supposed to be in this trial were excluded from participating because of things like adverse effects, lab abnormalities, etc.

So even before this trial is even STARTING, we are kicking out 1/5th of patients and screened them out because they aren’t able to tolerate these drugs.

Now, what is that going to do to your interpretation of results? Well, we already know that the patients we are going to end up randomizing/looking at for data are already these more robust, more “cream-of-the-crop” variety who are less likely to experience hypotension, less likely to experience hyperkalemia, etc.

And when we end up looking at the results from these patients who actually ended up in the trial, we still see significantly more hypotension, AKI, cough and hyperkalemia in the sacubitril/valsartan arm.

What this trial really tells me – is that even despite an intention to treat analysis, the presence of this run-in period in this trial really skews the type of “real world” patients that I might see in practice.

It also means that – heck yeah – sacubitril/valsartan really does cause hypotension and other things in practice, and I can probably expect to see even more of these ADRs in real life because of the way this trial was conducted.

(Side note – GDMT is very important in our HF patients and it’s important to get ARNIs on board for those who can tolerate it! This is not to say ARNIs are not an integral and important part of the GDMT bucket. I’m a big believer in ARNIs (….for HFrEF but that’s another story for another day).

So, how’d you do?

Hopefully today you understood these terms a little bit better, and can move on by incorporating these ideas, these analyses, more and more in your journal clubs so you start to get a more robust idea of what the trial actually means and what the data is actually telling you, rather than just reciting what happened in the trial and what was concluded.

Happy Holidays to all!

On a personal note, this was my first year coordinating/teaching core cardiology lectures for students at my institution. Shout out to each and every one of them for sticking with me through all 8 hours of lecture! They the real MVPs.