Welcome back, guys! Today we are going to start our journey into ✨valvular heart disease✨. This is a very, very pathophys heavy topic, and if you follow along, hopefully you won’t have to memorize anything because the pathophys will make sense. Because this is so pathophys heavy, we actually won’t even be talking about treatments until next time.

I think the biggest thing to focus on when we discuss pathophys is just the ability to slowly follow along and be able to understand each step that happens. You might not be able to recite the pathophys off the top of your head anytime soon, but hopefully you will have an appreciation for the effects of valvular heart disease and also what is actually happening in that heart.

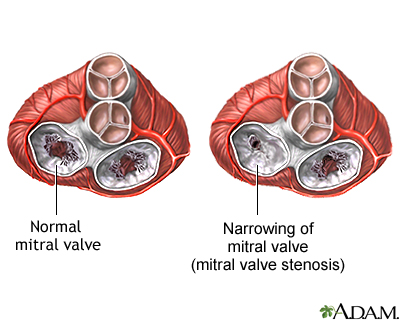

My goals for you are to understand what these valves look like when we say the words “stenosis” or “insufficiency” or “regurgitation” and realize why the heck these valve issues can become so important that we actually perform open-heart surgeries in these patients on bypass.

This is definitely one of our more dense discussions, so if you’re too tired to hang right now, I recommend coming back when you are feeling a bit more refreshed (think of this post as watching “The Last of Us” instead of just casually half-watching the episode of Seinfeld you’ve seen 10,000 time in the background).

Without further ado – as always, we’re going to start with the basics.

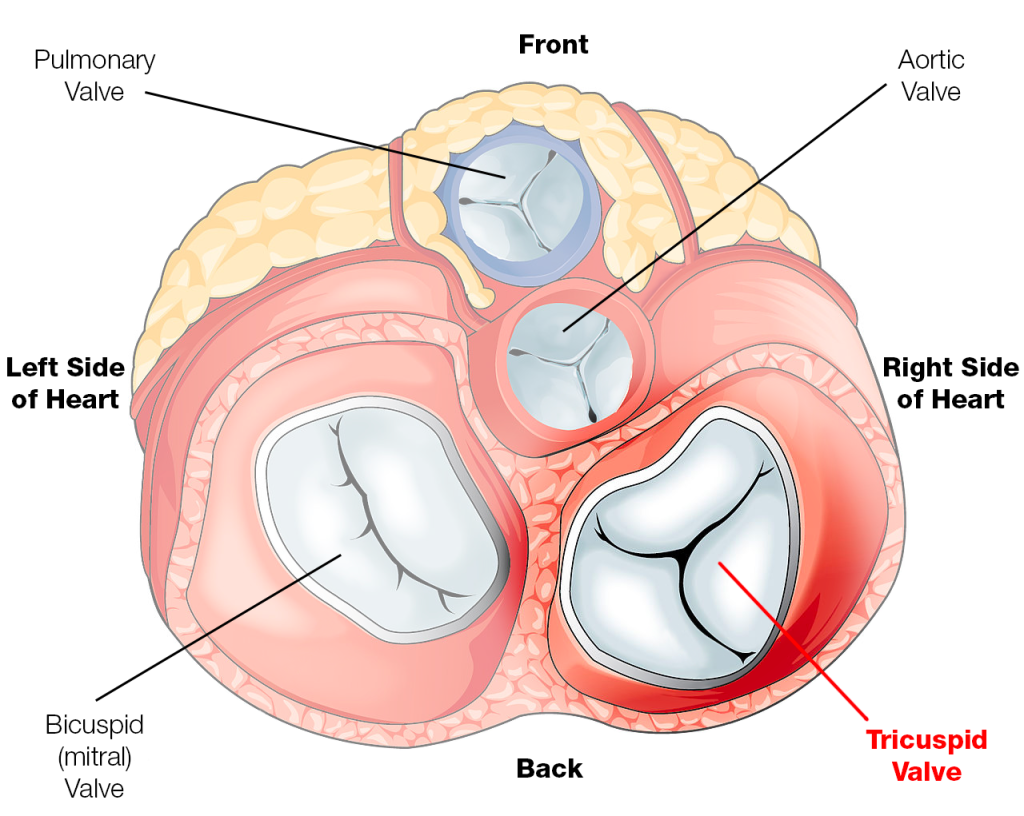

What valves do we have in the heart? (the main 4)

Let’s get you oriented again. If you need a better refresher on anatomy, check out the “coronary anatomy overview post.

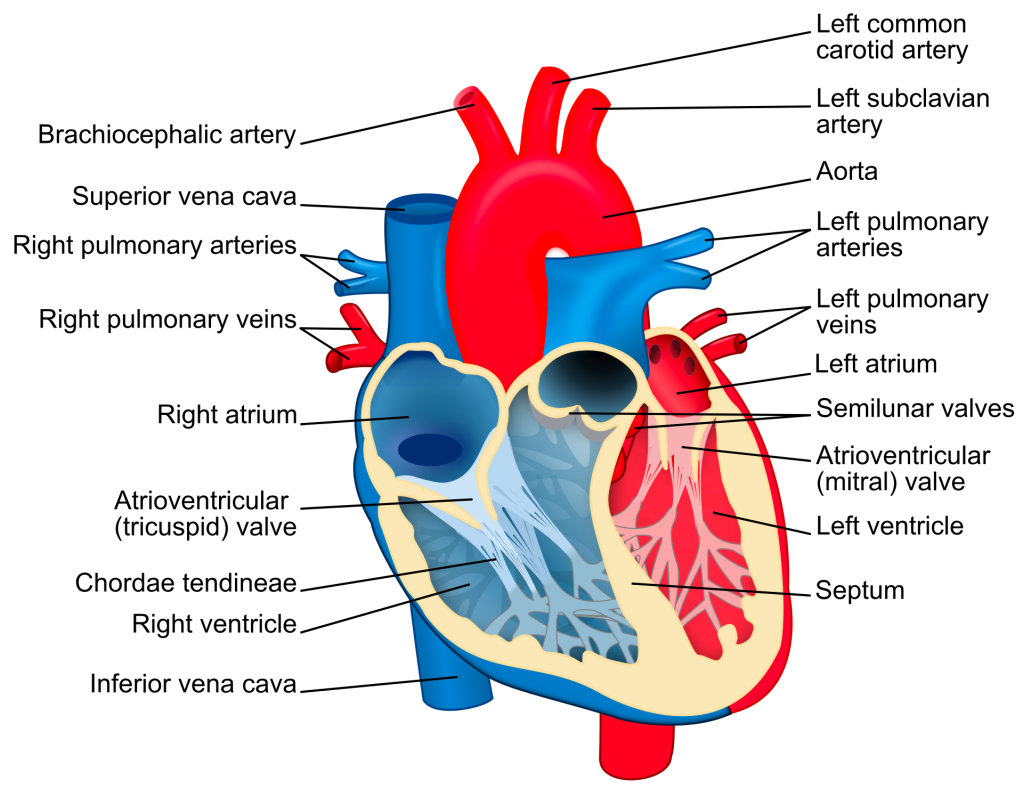

We got ✨4✨ main valves in our heart.

If we follow our typical blood flow route, our deoxygenated blood enters the right side of the heart, from the vena cava into the right atrium.

From the right atrium, blood moves through the tricuspid valve into the right ventricle.

The right ventricle squeeeeeeezes that blood through the pulmonary valve where blood then enters pulmonary circulation.

Once oxygenated, this blood flows into the right atrium, through the mitral valve to the left ventricle and finally out the aortic valve on its way to provide your body with nice oxygenated blood.

Check out the diagram below to follow along.

Luckily for us, I’d argue that two of these valves have really easy to remember names (we love that for them):

The pulmonary valve is the one that is our gateway to the pulmonary circulation, while the aortic valve serves as the gateway to the aorta and out to the rest of the body.

That leaves us with the tricuspid and mitral (aka bicuspid) valves. These can be grouped together as our AV valves – aka our atrioventricular valves, aptly named because of their place in the heart (again, we love when names make sense).

The mitral valve is also known as the bicuspid valve.

The bicuspid and tricuspid valve are aptly named because of how many leaflets they are supposed to have – with tricuspid having 3 and bicuspid have 2. Check out that figure above to visually see what I mean, and that gif to see them in ✨action✨.

Fun fact: Do you know why we call the bicuspid valve the “mitral valve”? It all goes back to its apparent resemblance to the mitre hat that bishops wear. (I guess I can kindaaa? see it)

You can remember this however you want to. This may not help ANYONE so feel free to disregard: I personally am not the most religious person, but when I was trying to memorize the names of the valves and their respective sides, it helped me to mentally associate this idea of the mitral valve being associated with something religious. Bishops are often seen as important within their religious congregations, and so the mitral valve must be on the tougher, stronger, “more-important” side of heart – the left side.

As you may remember from our core discussions that the left side of the heart – specifically the LV is generally regarded as the more powerful/stronger side (cue flashbacks of Dwayne the Rock Johnson). This is how I remember that the mitral valve is on the left side of the heart and the tricuspid on the right.

Our aortic and pulmonary valves are known as our 🌙semilunar🌙 valves🌙. Both of these have three leaflets, are are named semilunar due to the resemblance of each leaflet to a half moon🌙🌙🌙🌙🌙.

Low key always thought about what would happen if these valves just look like something different. Like idk, a pickle. Would the names reflect that? The pickled valves? Idk. Unclear.

(For the record, we also have other valves in our heart – like the coronary sinus valve or IVC valve – but these aren’t really often discussed/applicable clinically)

Ok, now we got the names and locations down. But why do we even have valves? How do they work?

It’s a good question. The whole reason we have heart valves is to prevent backflow of blood and to ensure forward flow. In other words – we want the blood to go forward, and to make it all go blood to flow in one direction.

Knowing this, the AV valves (aka the mitral and tricuspid valves) prevent the backflow of blood from the ventricles into the atria, and the semilunar valves (aka the pulmonary and aortic valves) prevent backflow of blood from either the pulmonary artery or the aorta into the right or left ventricle, respectively.

I feel like there is a common misconception that your valves themselves do the work of the opening and closing of them. That’s actually not the case.

The opening and closing of the valves are completely caused by the change in pressures during systole vs diastole.

What causes this? Why does this happen?

It might sound obvious, but whenever the pressure behind a valve is greater than the pressure in front of the valve, the valve will be blown open.

However, when the pressure in front of the valve is greater than the pressure behind the valve, that valve will be pushed closed and blood flow between chambers stop.

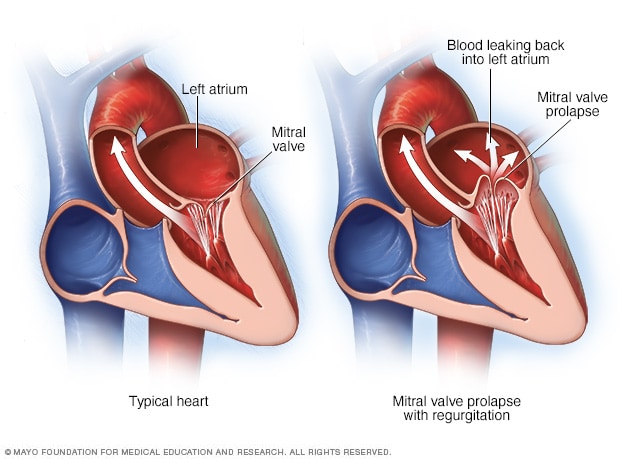

So the pressure itself takes care of the opening and closing themselves – but what’s to prevent those valves from protruding/ballooning backwards (aka prolapsing)? Afterall, these valves are just made up of flexible-ish tissue.

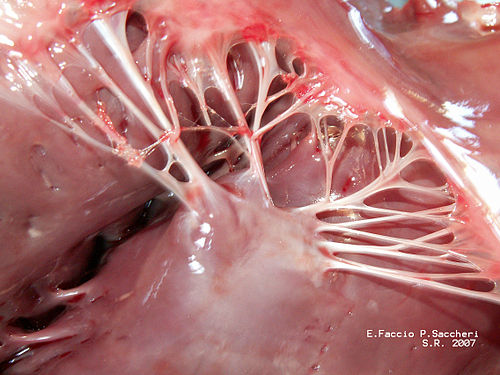

When it comes to your AV valves, these mitral/tricuspid valves are connected by these “chords” or strings called the chordae tendineae – aka…your literal “heart strings” (if only all these country singers knew they were talking about good ol’ chordae tendineae in their songs).

The chordae tendineae are these inelastic strings/cords of fibrous tissue that grow out of each ventricle and attach and anchor the valves into place.

These chords help keep the flaps of the valves from prolapsing when systole happens. I kind of think of them like literally strings anchoring the valves and giving them more tension as they close and open.

Attached to every chordae tendineae are papillary muscles. Their job is just to create even more tension to help the chords do their job. The chordae tendineae + the papillary muscles together are what we call the “subvalvular apparatus”.

Now you guys know I’m a very visual learner, so just in case you needed a visual about what I mean about “valve prolapse” – here it is.

This can also be seen IRL in this ECHO example as well:

Heart Valves and their Sounds🎵🎵🎵🎵

I feel like a lot of us might be familiar with the stereotypical “lub” and “dub” heart sounds, but have you ever thought about what is actually producing these sounds?

Well, spoiler alert – it’s the opening and closing of the heart valves that makes these sounds.

The closure of the AV valves produces the “lub” sound. This is also known as the first heart sound and also as the S1 sound.

The closure of the semilunar valves produces the “dub” sound. This is known as the second heart sound and also the S2 sound.

This is why things like heart murmurs (aka extra whooshing/swishing sounds that can be heard via stethoscope) can indicate abnormal blood flow over a valve, and prompt more investigation like an ECHO to see if there are any issues with those valves. Very often these murmurs are the first sign that physicians might notice that may indicate you may have valve issues. This is part of the reason why all doctors always listen to your heart sounds during your yearly physical.

I think in scenarios like this, it is even better to hear and see an actual video illustrating what I mean. If you’re interested, the below is awesome:

Stenosis, Regurg, Insufficiency, Oh My!

Just like anything else in the world, your valves can also have issues with them. Heck, you can even be born with issues with them.

The main issues we will be focusing on today are called valvular stenosis and regurgitation (also known as “insufficiency”).

Let’s first define what these words even mean.

Whenever you hear the word “stenosis”, I want you to think of a narrowing.

I used to think/associate “stenosis” with the idea of being calcified and crusty (like my 8 year old dog Luna). While stenosis can be due to or associated with calcifications, the term stenosis itself just means a general narrowing.

When you hear the term regurgitation, think about backflowing.

Gross example – I know, I know – but another word for vomiting is regurgitation, and although gross, it’s actually pretty spot on, since your stomach contents are meant to be pushed forward into the small intestine, not backup into the esophagus and beyond. OK enough vom talk, I’m getting nauseous just thinking about it (I alway say I’m a sympathy vomiter – if someone starts even dry heaving near me I will do the same).

There are a bunch of other potpourri issues with valves that can occur and include things like endocarditis, which is a whole other thing that we won’t be getting to yet (but maybe one day).

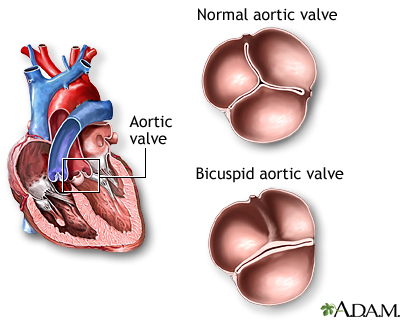

Lastly, we also have things like congenital (aka you are born with it) valve issues that can cause problems down the line, like a patient being born with a two-leaflet aortic valve instead of the standard three. This one will be closely tied into our discussions today.

Stenosis: In General

Let’s start with stenosis. Keep in mind that stenosis means a narrowing, so in this case we are talking about a narrowing of the valve. As you guys know by now, I’m visual so let’s actually see what we’re talking about here. Let’s use this aortic valve as an example below.

A healthy aortic valve should be soft, pliable, supple (sounds like we’re describing a boob job but bare with me). When it opens, it should open fully. However, in patients that get valve stenosis, their valves become hardened, crusty, stiff. This leads to an incomplete opening of the valve, so instead of getting a huge area where your left ventricle can easily pump blood out – your poor LV has to push extra hard to generate the pressures high enough to get blood through. Check out the difference in the animation below.

In today’s post, we’re going to discuss both aortic valve stenosis and mitral valve stenosis.

Why do patients get valvular stenosis?

Because this is a disease that is commonly due to calcification, hopefully it makes sense that the biggest risk factor/patient population we tend to see valvular stenosis in is elderly patients. This is because it takes time for calcium deposits in the blood to slowly drop off onto the surface of that valve and get it all crusty and narrowed. Similar to a lot of patients with afib, age is a huge risk factor for the development of valve stenosis. Check out the graph below to really get a visual of what I’m saying.

Besides older age, other risk factors include patients with diabetes, high cholesterol levels, and hypertension among some others. Another big risk factor is being born with congenital valve defects like we discussed above. Some patients are born with valves that have the “wrong” # of leaflets (e.g. bicuspid aortic valve instead of tricuspid). Because of this structural change, we often see these calcium deposits build up in these patients at a younger age.

Ok so my patient’s valve is a little crusty – why does it matter?

As we know in medicine, sometimes there are abnormalities with things but they may not be clinically relevant – so why do we potentially subject our patients to literal open heart surgery and bypass to replace these valves? What’s the big deal?

If severe enough, valvular stenosis is unfortunately a very big deal. To illustrate why, let’s delve into specific examples – aortic valve stenosis and then mitral valve stenosis, and what can happen if untreated.

Aortic Stenosis

Pathophys

Let’s talk about aortic stenosis first. First things first, as a refresher where is the aortic valve?

The aortic valve is a three-leaflet valve located between the left ventricle and the aorta. If this info is all news to you, definitely check out the coronary anatomy overview in the foundations section.

So in this scenario, instead of having a nice pliable open aortic valve, your valve is going to be very tight and narrowed – and the amount of space the blood will pass through will be very restricted.

What effect do you think this will have on the heart? Specifically on that left ventricle?

Now, instead of having a nice wide open valve for that LV to squeeze that blood through, imagine that LV has to squeeze all that blood out a teeny, tiny cocktail straw.

What kind of effect is that going to have on the left ventricle?

Let’s use a real-life example. Have you ever tried to blow air out of a normal sized straw or even like a smoothie/ICEE/boba straw? It’s not too hard, and it’s pretty easy to get the air out of your mouth/cheeks and through that straw.

Well – have you ever tried to blow air through a teeny tiny cocktail straw?

How does that feel in comparison? Is it easier? Or harder? What happens if you keep having to blow air into there for a whole minute?

Idk about you, but my cheeks start hurting when I try to blow through a cocktail straw, because it’s much much harder to get that air through.

This is because as the space gets smaller and smaller, the pressure behind it will get higher and higher.

This is exactly the same principle that we discussed in the foundations talk on BP – the smaller the space, the higher the pressure.

If you really think about it, severe aortic stenosis is essentially the same as having a very high afterload on your LV. Except instead of hypertension being the culprit, the culprit is actually a stenotic aortic valve.

What effect is that increase in pressure going to have on that LV? In order to answer that, you have to think back to your fundamentals: are ventricles made to withstand high pressures? How do they compare to the atria?

Just like Guardians of the Galaxy Chris Pratt, your ventricles can tolerate high pressures – they were physiologically built different than those wimpy atria because they have a much tougher job to do.

But what’s going to happen over time if your LV has to handle higher-than-normal pressures? What is going to happen when it is going to consistently work harder to keep forward flow?

I’ve said it a million times, but your heart is a muscle. If I went to the gym (which I don’t) and lifted a bunch of weights and worked out my biceps – what would happen over time? My biceps would grow and I’d get jacked.

Your heart isn’t any different – in aortic stenosis, over time, that hard-working LV is going to start hypertrophying and growing and growing.

And what do you think will happen as a result if that LV continues to grow and hypertrophy? (hint hint, it has to do with the amount of space in that LV)

If you said heart failure, you’re right. Specifically HFpEF or diastolic heart failure. That LV is going to get smaller and smaller as that muscle gets bigger and bigger, until eventually your patient will start developing heart failure. And unfortunately, structural changes like that are very hard, if not impossible, to reverse.

And if that muscle continues to grow, keep in mind the amount of blood that is supplied to it by the coronary arteries are somewhat fixed. There might come a point where the muscle layer is so thick, you aren’t getting adequate blood supply to feed all that muscle. And as a result, your patient may developed combined systolic and diastolic heart failure over time. Diastolic heart failure – because that LV space is so tiny – and systolic heart failure, because some of that tissue is now dying out because it’s not getting enough blood supply. Not good.

Symptoms

Now that you know a bit about the pathophys about what’s happening in AS (aka aortic stenosis) – what symptoms do you think patients might get with it?

The thing about a lot of these valvular problems is that oftentimes patients may not have *any* symptoms until the valves get really junked up. That’s because like we said, that LV is able to compensate in the beginning.

Realistically patients with mild AS may not have any symptoms and have no idea they have any AS. This is really a disease (for most patients) that is slowly progressing over decades, as those calcium deposits get on that aortic valve. Patients only start developing symptoms once the heart’s ability to adapt is just exhausted (I kinda think about this like the myth of Sisyphus rolling that rock forever up that hill).

However, as that AS gets worse and worse, patients will start to become symptomatic. The first symptoms will usually happen only on exertion since that LV is able to compensate when the heart is chilling and not overworking – but when that heart rate picks up and more and more blood needs to be sent out to the body, that LV will struggle pushing that blood out of a literal cocktail straw. Commonly patients endorse things like chest pain (angina), syncope (fainting), shortness of breath on exertion.

So oftentimes patients will present with new complaints of shortness of breath on exertion.

Overtime, if untreated, that patient will quite literally develop heart failure and so at this point symptoms can really happen at any time, depending on the degree of structural damage. Occasionally, it will become so severe that the LV can’t handle those high pressures anymore, and you’ll start to see some enlargement/build up of pressure within the left atria.

Mitral Stenosis

OK! Now that we’ve got AS under our belt – let’s talk about mitral stenosis. And honestly, the same, core concepts apply here too. As long as you have an understanding of the valve location, and the physiological workload of a typical atria vs ventricle you can reason your way through mitral stenosis as well.

First thing’s first: where is the mitral valve?

The mitral valve is located on the left side of the heart, and sits between the left atria and the left ventricle. It sees blood from the LA, and allows that blood to flow into the LV.

Now imagine that that mitral valve is all crusty and super tight and small. The same concept here – the pressure behind that valve is going to start getting higher and higher. Where is that pressure going to build up? In what chamber of the heart? And is this chamber used to high pressures? Can this chamber tolerate high pressures?

Given the location of the mitral valve, if there was stenosis of that valve, we’d see a backup in pressure within that left atria. Now, if you remember from our foundations talk, the atria just aren’t really built to withstand high pressures. Afterall, their job is pretty low-key – they just have to move blood through 1 valve, and..that’s really it.

Sure there’s some contract of the atria (known as atrial kick), but it’s really minimal compared to the ventricles. In fact, most of the blood flow from the atria to the ventricles is actually passive– what this means is that the valves open, and really just the presence of the valve being open allows the blood to move on through to those ventricles.

Because the atria aren’t built to push against high pressures and compensate and get super jacked, what we see in mitral stenosis is a ballooning of that pliable left atria as the pressure increases (think about your cheeks when you try to blow through that tiny straw). In a way, you can say that the afterload of the left atrium is very high due to this mitral stenosis.

This ballooning is going to cause complications…that we’ll talk about in a bit.

But because that left atrium can’t just get buff to handle those pressures, what you will start to see is the ballooning of that LA and then eventually the LA can’t handle those pressures and so that pressure increase will start backing up into the pulmonary vasculature. This will eventually cause pulmonary hypertension in these patients.

But your pulmonary vasculature also isn’t meant to withstand high pressures either. Keep in mind that when your LV contracts it generates approximately 120 mm Hg of pressure in your body, give or take. Meanwhile a pulmonary artery pressure of greater than 25 mm Hg is considered pulmonary hypertension.

So, as you might expect, this build up of pressure continues to back up, until we get to the right ventricle. Can ventricles withstand higher pressures? They can. But just like the left ventricle in aortic stenosis, in mitral stenosis what you will get overtime is a hypertrophying and expanding of that right ventricle. So this is how, if left unchecked, mitral valve stenosis can lead to right sided heart failure.

What kinds of patients get mitral stenosis?

Unlike aortic stenosis which is generally more common, especially in the older population, mitral stenosis is often caused by rheumatic heart disease. Ok what is that though?

I don’t know about you, but when I was a kid, I feel like I was sick all the time, and that commonly involved either my ear or throat hurting.

And lo and behold, I feel like everytime I went to the pediatrician, the first thing they did was take that godforsaken SWAB and shove it down my throat and make me gag horribly.

What they were testing for, and what pediatricians have a very low threshold to test for (and rightfully so), is strep throat. But why so aggressive on the testing?

As it turns out, Group A Streptococcus infections are no freaking joke. If left untreated, even for just a couple of weeks, they can cause something called rheumatic fever.

Rheumatic fever, although triggered by a strep infection, is not a bacterial infection but rather a misregulated response of the immune system as a result. During this response, the immune system can attack specific tissues in the body, most commonly the joints, brain, and also – you guessed it – the heart. The immune system can target the heart valves – in this case the mitral valve – and cause inflammation and damage to it, causing thickening of the leaflet (aka stenosis).

Though the incidence of rheumatic fever is very low in countries like the US, this is why strep throat is so commonly tested for – I have personally seen older patients who had their mitral valve replaced and underwent open heart surgery as early as 16 years old because of rheumatic fever complications. However, in many patients, there is a slow immune response to the initial infection, so stenosis can sometimes still take quite a few years.

Why does left atrial ballooning matter in patients with mitral stenosis?

As I alluded to above, the left atrial ballooning we see with mitral stenosis can cause a big complication in a lot of patients, independent of heart failure.

Can you guess what it might be? Keep in mind we are talking about the left atrium, and in this case, we are going to see stretching and mucking around with that left atrial tissue.

That tissue is going to get irritated and pissed off.

And as a result, patients with moderate-severe mitral stenosis commonly develop atrial fibrillation. As that left atrial tissue balloons out, stretches, and undergoes this structural shift, a bunch of ectopic points of conduction can form in that LA and – *voila* – you got yourself afib.

But this ain’t your typical rodeo AF… this is a *special* type of AF known as valvular afib. Depending on who you ask (Europeans, I’m lookin’ at you) – this term is a little passé but it is still used in the latest rendition of the American guidelines.

Valvular AF is a special beast, and is currently defined per the American guidelines as AFib in the presence of mechanical heart valves AND/OR moderate to severe mitral stenosis.

Why must we categorize this separately? It all has to due to risk of thrombosis in these patients. Whereas your typical CHADS2VASC (in NVAF) score of….4….gives you an average yearly risk of stroke of ~4.8%, patients with valvular AF have a much much higher risk of systemic embolism – and I’m talking a whopping 20-30% per year! It’s important to recognize the presence of these things when assessing a newly diagnosed AF patient because as you may recall from our AF OAC talk, these patients need to only be managed on warfarin, and NOT DOACs.

To me, it kinda makes sense that AF in mitral stenosis would cause a high risk of clot. Afterall, the main reason clot forms in AF to begin with is due to stasis, and that LA quivering. Now imagine having that AND having that blood struggling to move out of that LA and through the the LV. The limit of stasis does not exist.

Symptoms

Just like we see in AS, the first symptoms in mild mitral stenosis can be seen on exertion, and are actually symptoms that can mimic left sided heart failure, without any actual left ventricular damage/failure happening. As these patients progress and develop AF, the AF just makes it just that much harder for blood to flow through that mitral valve, now without even that “atrial kick” to support flow through. If progressed to right sided heart failure, patients will get the typical symptoms seen with right sided heart failure and a backflow of pressure into the venous circulation such as edema, fatigue, abdominal distension and ascites.

[Insert brain break here]

Aortic Regurgitation aka Insufficiency

Now let’s move on to valve insufficiency aka regurgitation. Remember that in these scenarios, we are basically dealing with “leaky” valves – valves that do not seal well and do not do their job at preventing backflow.

What kind of patients get aortic regurg?

Let’s start with aortic regurgitation. Again: location, location, location. The aortic valve sits between the LV and the aorta. Like aortic stenosis, patients can develop aortic regurgitation with things such as advanced age (aka the valve degenerates as your patient gets older and older) or also in patients born with congenital valve issues (aka born with the wrong # of leaflets). Things like infections of that valve (e.g. endocarditis) can also break it down causing improper closing. Hopefully it makes sense that patients that have dilated aortic roots can also get these leaky aortic valves. This can happen in patients with chronic hypertension or in patients with connective tissue issues, such as patients with Marfan’s.

pathophys of aortic regurg

Ok so we’re going to Magic school bus this now.

Imagine you are in that LV and with every squeeze and spitting out of 1 stroke volume of that LV, you get a bunch of that blood back in because of a leaky valve.

What’s going to happen in that LV?

Well, more and more blood is going to start accumulating in that LV, right? This is what we fancily call increasing end diastolic volume – quite literally, the amount of blood that the LV will hold at the end of relaxation will keep increasing.

Your LV wants to be a team player. It really does. In order to adapt, your LV allows itself to be somewhat more pliable/flexible so it can continue to accept higher and higher volumes so it doesn’t have to increase the amount of pressure in there.

As this progresses, your LV has to start pumping out more and more volume in order to make sure your body/aorta is getting enough blood in there to supply the body with oxygen – in other words, it has to squeeze more and more blood out and increase stroke volume in order to ensure enough forward flow.

However, if you remember our basics hemodynamics talk – what happens to pressure as volume increases? Think back to our hose analogy. Does the hose shoot the water further as you increase the amount of water flowing through the spout?

You bet it does. Because of these high volumes into the aorta, the aorta starts getting chronically high pressures. Because of these high aortic pressures, your struggling heart now has to pump against a high afterload that it ironically created.

If continued to be left unchecked, all this volume your LV has to handle along with this high afterload will cause pretty severe hypertrophy and structural changes of that LV, and eventually these patients will get these really round ventricles and have more contractility as they develop heart failure.

Symptoms of aortic regurg

Just like some of our other valvular issues, the symptoms of aortic regurg are slow to happen. This is all because our LV is able to compensate, and can expand a large amount to deal with the extra volume and is also pretty resilient against the initial high afterloads. When they do develop symptoms, they are very typical of left sided heart failure and can also experience angina or chest pain, because of their heart trying to work hard managing that high volume and afterload.

Mitral Regurgitation/Insufficiency

What kind of patients get mitral regurgitation?

One of the most common etiologies/causes of mitral regurgitation is due to something called mitral valve prolapse. This is when either the chordae supporting the leaflets or the leaflets themselves get all “floppy” and cause the valve to incompletely close.

It can also be caused from patients with messed up papillary muscles as a result from coronary artery disease – in other words, if your heart gets a decrease in blood flow to the area supporting these muscles, some of this muscle tissue can die, and it will no longer be effective in getting a tight seal. Another reason patients get get mitral regurg is simply from the stretching of that left ventricle in patients with things like volume overload (this is called functional mitral regurg).

pathophys of mitral regurg

OK so you got a leaky mitral valve. Again – know your location.

The mitral valve sits between the left atrium and the left ventricle. Think about being the blood within that LV.

You have two routes to go – you can either be pushed out to the aorta, which carries a decently high pressure associated with it (~80 mm Hg), OR you can flow back into the fairly low pressured left atria through a leaky valve. Just like many of us do in life, blood also wants to take the path of least resistance.

The “afterload” associated with that very compliant left atrium is wayyyyyy lower and easier to get through to than the normal forward flow into the aorta.

So your left ventricle is going to squeeze, and a good chunk of that blood is going to go backwards through that leaky valve into the left atrium. Because the left atrium has to deal with this higher volume and because the left ventricle is losing a lot of blood backwards, both your left atrium and the left ventricle have to accommodate a higher filling volume (aka preload) in order to make sure the net result is still adequate forward flow.

Let’s say that in different words. Let’s say when your LV squeezes, it loses 40% of its stroke volume to the left atria; the other 60% goes to the body. So – unrealistic values – but let’s say an adequate stroke volume for you is 10 mLs – the body will only get 6 mLs per beat instead of the 10 mLs it needs thanks to this regurg.

If your preload stays fixed, then 60% of normal stroke volume that should be 100% ain’t going to cut it. So the only way to fix this is to increase the amount of volume that these chambers are dealing with. So now let’s say you have more volume and your SV is actually 16 mLs instead of 10 mLs. You’ll still have the same issue – 40% of that will be lost to the left atrium – but because you are dealing with a large volume, the 60% that your body will receive will now be 10 mLs.

Still with me?

As that mitral regurg gets worse and worse, and the valve more and more leaky, severe mitral regurg occurs when more than half (>50%) of that stroke volume is lost the the left atrium.

In order to compensate, it should hopefully make sense that the left ventricle actually has to double its output. Because again – if you need that 10 mLs of stroke volume and you are using 50% per contraction – in order to compensate that LV will start having to spit out 20 mLs of stroke volume to ensure 10 mLs gets out to the body.

This is…..rough on that poor LV. What you end up with is crazy dilation of both that LV and left atrium, as well as hypertrophy of that LV since not only does it have to get all dilated to support the new volume, but it has to work harder than normal to contract double of its typical stroke volume out.

The heart is able to compensate for a long time – but eventually, something’s got to give. There comes a point where that super dilated, very stretched out and thickened left ventricle cannot compensate anymore.

The ironic part about these patients is even though they can have both systolic and diastolic issues, their EFs often stay “normal” because of the increased end diastolic volumes.

symptoms

Just like our other diseases, because your LV is technically able to get more volume and contract harder, especially in the beginning, patients may not have any symptoms, even on exertion – since after all, their cardiac output shouldn’t really change since their stroke volumes aren’t changing (remember CO = HR x SV). However, if they eventually tip over, their symptoms will be very similar to that of left sided heart failure.

Interesting but sad real life example of how valvular disease can be deadly:

The above little majestic creature was my childhood dog named Lucy. Now when we adopted Lucy, at her first vet appointment, we were told she had a heart murmur. Vet didn’t make it seem like a huge deal (and granted we weren’t the best with taking her to the vet every year). Lucy was totally fine, until at the age of 8 she started coughing one day.

It wasn’t an every second type of cough, but here and there she would start having a wet cough. We took her to the doctor and they got a chest xray on her.

And lo and behold they saw a really really big heart, a ton of pulmonary edema – in short, that valvular disease that Lucy probably had since she was a puppy finally caught up to her, and she could no longer compensate – she had developed heart failure.

She was still completely “normal” with the exception of the cough – we took her in for an ECHO before they would start therapy on her, and unfortunately the stress of the ECHO and being around all these people tipped her over, and she had florid ADHF and had to be put to sleep that same day.

I, of course, didn’t know about any of this stuff as a teen, and learning it over the years has really made me understand what was going on with our little Luc all those years ago, and really hits home to me why valvular disease is such a big deal and needs to be treated.

Thanks for hanging today – I know this was a dense one. Stay tuned for part 2 where we will be discussing valve replacement options and pharmacotherapy for these different patients!