Hey everyone! Today we are going to discuss what therapies we have to get our post TAVR patients on, and why. ICYMI, I would recommend reading Part 1 first.

We already discussed what TAVRs are – essentially a less-invasive, catheter-based version of replacing a patient’s aortic valve. Instead of having to undergo open heart surgery, cracking the chest open, going on bypass, etc – you just need to make a little incision in a large artery and thread a catheter through and deploy the valve that way.

To get a good idea of what this procedure looks like, I would recommend watching this video. Also special shoutout to UC Davis where I did my residency (Dr. Southard was a fantastic teacher on rounds).

When I think of TAVRs, I almost think about them as a valve version of a cardiac stent – after all, coronary artery stenting was really the basis behind where the TAVR inventor got his ideas from (he even called the TAVR valve a “stent-valve”).

Now, let’s think back to the TAVR procedure and some complications that can happen as a result. We already talked about the main procedure-related complications – mostly access site (wherever that nick to access the artery was made) bleeding and strokes that form as a result of some of that old calcified valve flicking off, or a clot forming during the procedure.

Similar to how we approach surgical valves (or really any foreign object exposed to our bloodstream) something that has to be on the forefront of our minds when thinking about post-TAVR management is reducing the likelihood of valve thrombosis and systemic embolisms (check out clot formation 101 if you need an overview about why clots form).

When we introduce that new valve in the area around your old, crusty aortic valve, squish that old valve out of the way, and leave this new valve in its place, we are essentially telling our body’s coagulation system to wake up and get going.

The tissue damage that is caused by the manual crushing of the old aortic valve exposes tissue factor (TF) to the bloodstream, activating the extrinsic coagulation cascade. And that brand new shiny tissue valve is also a foreign surface in the bloodstream which activates the intrinsic coagulation cascade.

Just like we do for any valve replacement or coronary artery stenting, we have to worry about ameliorating these risks and protecting our patient from forming a clot on or near this new valve surface. If clots form here, the risk of a stroke is very high...all that clot needs to is flick off that aortic valve and take a 1-way trip up the aorta and into the brain (check out the coronary anatomy post if you need a refresh on the anatomy of the cardiovascular system and why a clot on the aortic valve would likely cause a stroke).

When talking about what kind of antithrombotic therapy we need in these patients, I’m going to chat a little bit about

- what we used to do, and

- how the landscape of antithrombotic management has changed in recent years.

The original TAVR antithrombotic regimen of choice

When TAVRs were first designed, created and used in the early 2000s, because they were intellectually modeled after coronary artery stents, their antithrombotic regimen was also modeled after what we do in coronary artery stenting: DAPT.

At the time, taking a page out of what we did for coronary stents, the practice was to use clopidogrel + ASA for around 3-6 months, followed by aspirin monotherapy.

Early post-TAVR management involved DAPT (clopidogrel + ASA) for 3-6 months followed by aspirin monotherapy.

The reasons behind this were likely multifactorial, the strongest being that TAVR was somewhat analogous to PCI. Because TAVR was modeled after coronary artery stents, the antiplatelet therapy regimen was largely borrowed from the same protocols that were used in PCI. Because we used DAPT post PCI to prevent thrombosis, it was then assumed that this would be the best bet for managing our post-TAVR patients.

The cutoff of 3 to 6 months was employed because studies have really shown that 3-6 months is the amount of time it takes post-implantation for the valve to start endothelizing, dramatically reducing the risk of thrombosis (after all – if there is no metal/foreign object exposed to the bloodstream, the risk of thrombosis really goes away).

Because TAVR was also a fairly new procedure, there was a lot of early concerns about the possibility of thrombosis, specifically valve thrombosis, strokes/TIA, or even coronary embolization. The interesting thing is we really didn’t have any data to back up this strategy – in other words, DAPT was kinda just what was chosen from the get-go, and in the absence of evidence saying the contrary, this more aggressive platelet inhibition strategy was employed.

As an aside – learning about the way we figured out things in medicine was always very interesting to me. When I was younger there was this thought that we just “know” what to do in medicine. But the more you learn about medicine, the more you learn that we are just making it up the best we can as we go along with the best data we have at the time.

When people start questioning the “status quo”…

Although the use of DAPT was standardized for our TAVR patients, there were some people questioning the need for this aggressive platelet inhibition pretty early on.

Why the questioning? It’s most likely due to a few reasons.

1) we know that in surgical bioprosthetic aortic valve replacements, aspirin alone is generally enough and our standard of care to manage these patients and to protect them from thrombotic complications. One could argue that TAVRs may cause less thrombotic complications than SAVRs since they are greatly less invasive and do not involve the cutting out the old valve.

2) at the end of the day, the environment around the aortic valve is greatly different than the environment around our coronary artery stents. The coronary arteries are waaaay tinier/narrower, have slower flow, and lower pressures. In contrast, the area around the aortic valve is high pressure, high flow, and has a fairly wide circumference. All of these factors promote the idea that coronary arteries are likely far more likely to develop a clot when a stent is deployed there, versus the area around a TAVR valve.

3) Safety. We also know that SAPT is also overall safer in terms of bleeding versus DAPT. There could be a potential benefit from de-escalating therapy and reducing the risk of harm in terms of bleeding events.

Ussia et al. challenge the norm

In 2011, Ussia et al. decided to put this idea into practice. They conducted a small (n~80) randomized, single-center, prospective pilot study that compared DAPT (clopidogrel + ASA) for 3 months versus ASA 100 mg PO QD (the 100 mg dose was used over the 81 mg dose likely because the 100 mg dose is what was available in the country where this study was conducted).

The primary endpoint looked at all the important stuff – major adverse cardiac and cerebrovascular events – and maybe not surprisingly to some, they found that the cumulative incidence of their primary endpoint at both 30 days and at 6 months (the end of that most thrombotic time period post implantation) was not statistically different between groups.

Though promising, Ussia et al recognized that these results must be confirmed by larger RCTs, but they largely paved the way for this question to continue to be studied.

Others follow suit and lay the groundwork for something big…

Over the next couple of years, a variety of trials, studies and meta-analyses are published looking at this same question. In 2014, we had the SAT-TAVI trial by Stabile et al investigate this question again- this group was somewhat larger (n~120). Once again, they did not find differences in terms of thrombotic outcomes.

In 2017, the ARTE trial was published by Rodes-Cabau et al and was a prospective, randomized, open label trial of ~220 patients looking at DAPT vs ASA and showed that SAPT tended to reduce the occurrence of major adverse events following TAVR, reduced the risk for major or life threatening events, without an increased risk of MI or stroke.

These results were repeated in 2019; a meta-analysis by Kuno et al. investigated a slew of different antithrombotic therapies post TAVR. With a robust total population of over 20,000 patients, they found that SAPT (ASA alone) had a significantly lower rate of bleeding versus DAPT, without any differences in stroke. In other words, this meta-analysis hinted that choosing ASA upfront not only reduced the risk of bleeding, but didn’t have any trade-off in the incidence of stroke and still offered enough thrombotic protection for these patients.

These important studies and trials over the span of a decade paved the way for something bigger to confirm their findings and change practice….

The POPular-TAVI trials

In 2020, we finally had a large RCT come out confirming the results of all the studies previously. The PoPular-TAVI trials can be a little confusing, since there are 2 different papers published based on what cohort they studied. One branch (cohort A) of the study looked at your normal run-of-the-mill patients post TAVR and compared aspirin with or without clopidogrel. We will talk about the other cohort a little later (I’m sure the suspense is killing you).

This arm of the POPular TAVI trial was an RCT in patients undergoing TAVR who did not have an indication for anticoagulation (in other words, they weren’t already on OAC for a hx of VTE, or AFib, let’s say). Over 600 patients were randomized to either receive aspirin alone or aspirin + clopidogrel for 3 months. The primary outcomes looked at bleeding and non procedure related bleeding over a period of 12 months. The secondary outcomes look at a composite of death from CV causes, non-procedure related bleeding, stroke or MI (aka ischemic + bleeding complications together) and a composite of death from CV causes, ischemic stroke or MI at 1 year (aka ischemic outcomes alone). The results indicated that the incidence of bleeding and composite of bleeding or thromboembolic events were significantly less with ASA versus DAPT for 3 months. When looking at thromboembolic events alone at 1 year, ASA reached non-inferiority but not superiority (which is kinda expected).

Though the POPular-TAVI trial greatly impacted clinical practice, this rec is not included in the latest valvular US guidelines because POPular-TAVI was unfortunately not published in time to be considered for inclusion.

However, because the European Guidelines (ESC) were published a year later, the recommendation to use SAPT after TAVR was incorporated.

Long story short, in most patients post-TAVR who don’t have a compelling indication for OAC, SAPT is now really the standard of care.

Why do we even do antiplatelet therapy in these patients post TAVR, rather than oral anticoagulation?

Like I said above, we did DAPT from the start with little to no evidence, and so at some point or another the question came up whether or not OAC would be a better strategy in these patients. This is what the GALILEO trial looked at, and found that patients who received rivaroxaban 10 mg PO QD had a higher risk of death or thromboembolic complications as well as a higher risk of bleeding than an antiplatelet-based strategy.

In other words – OAC in patients that don’t have an indication for OAC? Not good.

What about those with a pre-existing indication for OAC?

Now that we know that SAPT is the best, evidence based treatment of choice post TAVR in most patients, I’m sureeeee you are thinking – what do we do for patients that need to be on oral anticoagulation for another reason (e.g. AFib, VTE)? Do we put these patients on OAC + SAPT? Do we do OAC alone?

Luckily for you, this is where cohort B of the POPular-TAVI trial came in.

This trial sought to answer that exact question. The investigators conducted an RCT of patients undergoing TAVR who had a pre-existing indication for OAC. Patients were then randomized to either receive clopidogrel (aka OAC + clopidogrel) or no clopidogrel (aka OAC) for 3 months. The trial found that serious bleeding was higher with OAC + clopidogrel versus OAC alone. OAC alone was also non-inferior to OAC + clopidogrel, though the non-inferiority margin was big.

The POPular-TAVI cohort B trial showed that OAC alone, rather than OAC + clopidogrel should be used post-TAVR in patients with an indication for OAC.

This trial then became the basis for ESC’s other statement recommending OAC (rather than OAC + clopidogrel) in patients post TAVR with a pre-existing indication for OAC.

Now if you’re me, I know what you might be thinking – it’s kinda a bummer that this trial looked at OAC + clopidogrel, and not OAC + ASA. Afterall, it’s aspirin, not clopidogrel that we put on for the other patients post TAVR.

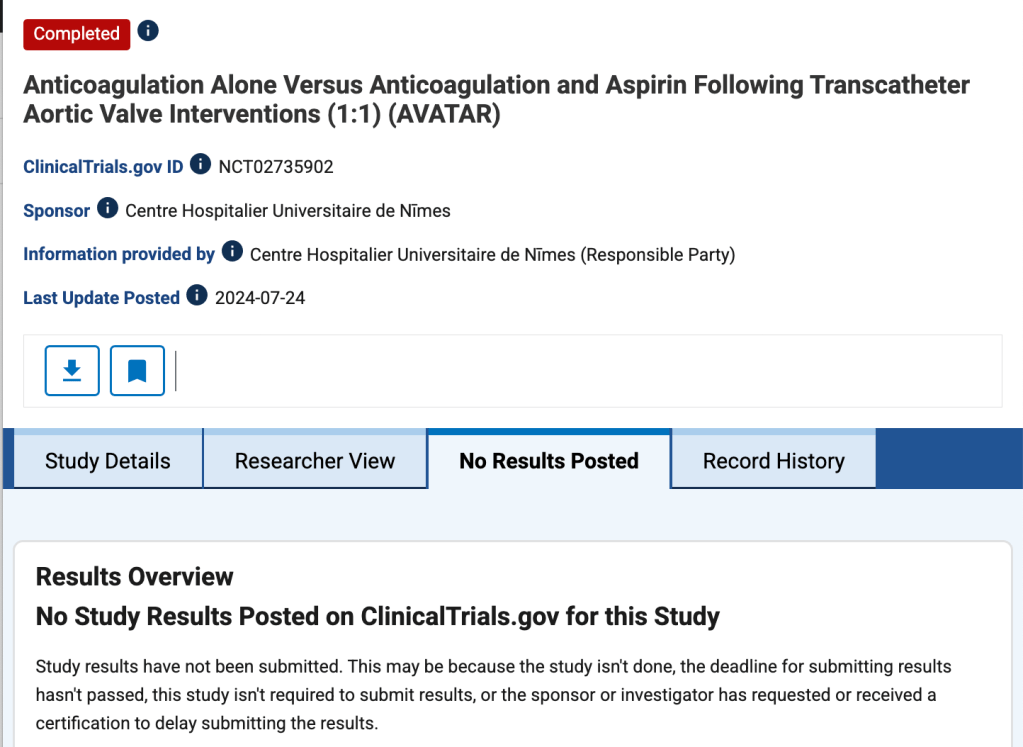

The AVATAR trial sought to clarify this further.🎉🎉🎉

But although to my knowledge, although completed, the results haven’t been published anywhere or presented at any conference.

Womp, womp. Hopefully those results will be posted sooner than later.

And that, my friends is the antithrombotic management of patients post-TAVR. Most patients will get SAPT with aspirin. In those with another indication for OAC, most patients will get OAC alone.

OK, one more thing but this is just extraneous info, more related to drug literature analysis (so totally skip if you want)!

Whenever you read a trial, always make sure to keep a close eye on how trials are defining their endpoints. Afterall, I always say a trial can basically do or say whatever they want as long as they define what they mean.

A good example of the quirks behind how trials can define their endpoints would be how they defined bleeding in the POPular-TAVI trials. Now, keep in mind, the majority of bleeding that we worry about post TAVR is access site bleeding, or the place where we inserted the catheter to conduct the procedure.

However, the investigators of this trial defined their procedure-related bleeding as any BARC type 4 severe bleeding.

BARC is one of our commonly used methods to characterize bleeding in trials – other commonly used ones are GUSTO, TIMI, and ISTH.

If you actually look at BARC type 4 bleeding, you will see that this bleeding is also called “coronary artery bypass grafting-related bleeding“, aka the type of bleeding you would see after an open heart surgery.

Bleeding under this category includes “perioperative intracranial bleeding within 48 hours; reoperation after closure of sternotomy for the purpose of controlling bleeding; transfusion of 5 U of whole blood or packed red blood cells within a 48-hour period; chest tube output 2 L within a 24-hour period.”

Considering TAVR patients don’t have 1) a sternotomy to begin with, or 2) chest tubes, this type of bleeding may not have been the best way to categorize true bleeding for these patients.

None of these capture your typical TAVR-related bleeding – and so – for the purposes of the POPular-TAVI trials, access site bleeding was considered non-procedural bleeding.

At the end of the day, the POPular TAVI trials still were landmark trials, but while we were talking about them, I thought it might be a good little drug lit lesson to throw in there. Always look at how trials define their endpoints. A lot of times this info might be hidden in the supplemental, but it may or may not change how you view the clinical relevance of the results.

Until next time –