I don’t know about you, but looking back to when I took cardiology in school, I’m pretty sure I had no real grasp on what preload or afterload really meant. They were words that were tossed around a lot, and I remember memorizing different meds and knowing which ones decreased preload, which ones decreased afterload, etc.

**My classmates testing me prior to a CARDS exam:**

Nitroglycerin? ……..it’s a ……preload reducer.

Nicardipine? ……pretty sure that one was mostly an afterload reducer.

Cool, got an A on the exam.

However……. if you asked me what this actually meant, I don’t think I had a clue.

The truth is…..these terms aren’t really hard to explain – if you get what they mean.

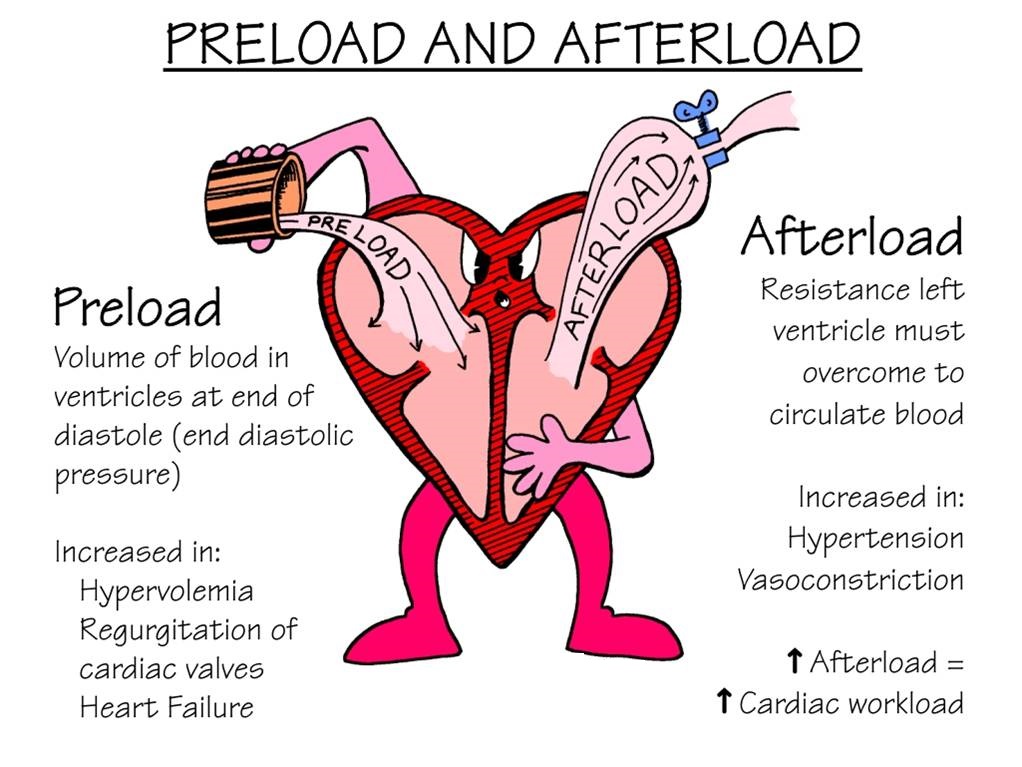

The above diagram is a little dated, but I am still obsessed with it. Let’s break it down.

Preload

Let’s start with preload. When you think of preload, I want you to think of volume.

The official definition of preload is the amount of sarcomere stretch experienced by the cardiac muscle cells at the end of ventricular filling during diastole.

Take a second to think about and visualize what that means.

The more volume in the ventricles at the end of the heart’s relaxation period – the more stretch – the higher the preload. Preload is basically just the stretch of your ventricle’s muscle cells just before your heart contracts.

A good analogy to visualize preload is blowing air into a balloon. Think of the balloon itself as your ventricles and the air that you blow into the balloon as blood. The more air you blow into the balloon, the more stretch on the ventricles.

Because we are thinking about volume of blood in the heart, let’s think about factors that might increase preload. Patients that are hypervolemic (aka volume overloaded) in their vasculature will have increased preload.

Now, what can decrease preload? Well, diuretics can. By increasing water excretion and getting rid of circulating blood volume, diuretics act to decrease preload.

Anything that decreases venous pressure also will decrease preload.

In other words, the lower the pressure in the veins, the less blood volume that will rush into the heart. Any drug that acts to dilate veins will act to decrease venous pressure and therefore decrease preload. Nitroglycerin is a classic example of an intravenous (IV) medication that is a venodilator (acts to dilate the venous system) that acts to decrease preload.

I’ve had some learners get a little confused with this idea. After all, if you are dilating the veins, won’t we be able to get more blood through the veins?

I like to consider a real-world example for this one. Think about a garden hose.

When you have an open garden hose, the water tends to pour out and fall out of the bottom right? But what happens when you put your finger on the end of the hose and make the area the water needs to go through smaller?

That smaller stream of water getting through will go through much harder, much further, and much faster because the pressure it is experiencing at the end of that hose has increased.

The rules of physics don’t change for your blood in your vessels. The larger the vessel, the less pressure within. The more you constrict that vessel, the higher the pressure.

Afterload

Next, let’s talk about afterload. When you think about afterload, I want you to think about pressure. The afterload is the amount of pressure that the heart needs to exert in order to eject blood during ventricular contraction.

Look back at that 80s cartoon at the top of the page. Remember that your aorta, your vessels – all have a pressure associated with them (remember systemic vascular resistance?).

In order to push blood out of your left ventricle, through the aortic valve, into the aorta and out to the rest of your body, your left ventricle will have to overcome the pressure within the aorta and vessels in order to keep forward flow.

The higher the afterload, the harder your heart has to contract to ensure forward flow and perfusion to the rest of the body.

Let’s talk about what factors can increase afterload. Patients with an issue with their aortic valve (the valve that separates the left ventricle from the aorta), known as aortic stenosis, have increased afterload.

Whenever you hear the term “stenosis” I want you to think of a narrowing. Patients with aortic stenosis have very narrowed, calcified, hardened aortic valves. Because of this, their aortic valves can no longer open wide and let blood flow through easily.

Because of this, your left ventricle will have to push hard in order to get all of its stroke volume through this teeeny, tiny opening during the contraction period.

Patients with hypertension who have elevated SVRs also have high afterloads.

Now, what are some agents that we can give to decrease afterload? Any agent that works to dilate the arteries will decrease afterload. Some of these agents include calcium channel blockers, hydralazine, or ACE inhibitors. We will eventually discuss all of these classes of medications in detail.

There you have it. Preload and afterload. Hopefully these core cardiology concepts are now easier to grasp.

amazing thank you so much

LikeLike

THANK YOU! Love the simplicity and the funny pictures.

LikeLike

That was probably the best and most simplistic way I have ever heard it described! Thanks!

LikeLike

for the first time i am getting this concept so clearly.

THANK YOU SO MUCH

LikeLike