Welcome back to another post – today we will be talking about our first anticoagulant class: our heparinoids. We will be focusing on the basics – aka mechanism of action – of these agents. This talk will be short but also v. important in our understanding of anticoagulants.

Prereadings: To get the most out of today’s post, I recommend you read the following post beforehand:

Our heparinoids are divided up into three main subclasses:

- Unfractionated Heparin (UFH)

- Low molecular heparin (LMWH; examples include dalteparin, enoxaparin)

- Fondaparinux

General Mechanism of Action

All of our heparinoids are considered anticoagulants which means they work on the coagulation cascade to prevent the formation of clots and/or from clots from getting larger. They do not do anything to existing clot (unlike fibrinolytics that can help break down that clot).

Let’s bring up a picture of our beautiful coagulation cascade.

One thing that we did not talk about during our discussion on clot formation is antithrombin.

Antithrombin is a substance present in the blood that is the primary inhibitor of thrombin. By working to inhibit thrombin (aka factor II), antithrombin naturally prevents blood from clotting.

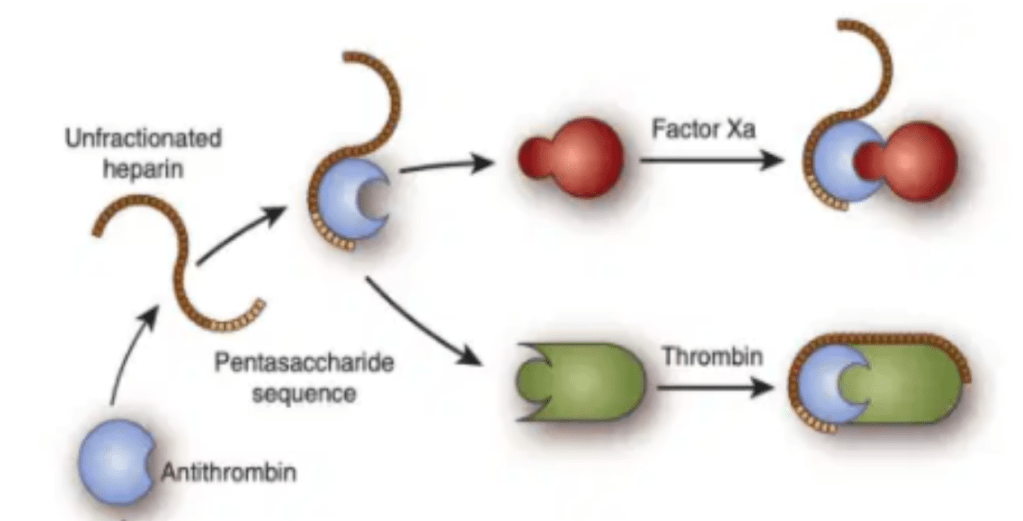

All heparinoids need antithrombin in order to work. When heparinoids bind to antithrombin, they can accelerate and increase the activity of antithrombin to inhibit coagulation factors, thus exerting an anticoagulant effect.

All of the heparinoid agents are considered indirect anticoagulants. In order to work, they need antithrombin. Without antithrombin, they cannot produce their effects.

When you are considering the different effects between the heparinoid agents, I want you to think about two factors: factor Xa and factor II (thrombin).

When comparing the different effects of each heparinoid agent, remember the factors Xa and II.

In order to remember the effects of each agent, I like to first think about the structure of these heparinoid agents. Let’s take unfractionated heparin as an example.

I like to think of unfractionated heparin being comprised of two distinct pieces:

- A core pentasaccharide sequence

- A tail

The core pentasaccharide sequence is the section that will bind to antithrombin and will inhibit factor Xa.

The long tail is responsible for wrapping around and thus inhibiting factor II (thrombin).

See the visual above to get a better idea of what I mean.

What’s the physical difference between UFH, LMWH, and fondaparinux?

Unfractionated heparin is heparin in its “most natural form”, harvested from the intestines of adult pigs. Unfractionated heparin is exactly what it sounds like – unfractionated (aka not cut up) so each molecule will have the core pentasaccharide sequence and plenty of tail.

Low molecular weight heparin (LMWH) is heparin that has been fractionated – or cut up – and so although it still has the core pentasaccharide sequence to bind to antithrombin, it does not possess as many long tails as UFH, but rather a lot of those tails get cut off in the process.

Fondaparinux is not sourced from pig intestines at all – it is actually synthetically made – and only consists of that core pentasaccharide sequence. None of the molecules of fondaparinux possess that “tail” we see with UFH or LMWH.

Now that you know how these drugs differ physically, let’s talk about how they differ in activity.

Remember how we discussed that the pentasaccharide sequence allows for the inhibition of factor Xa and the tail is what allows for the inhibition of factor II?

Because of this:

Unfractionated heparin has a Factor Xa:II inhibition rate of 1:1. This is because all those molecules have that nice long tail that allows for factor II to be inhibited.

Low molecular weight heparin has less Factor II activity (shorter tails). Because of this, its Factor Xa:II inhibition rate between 4:1 and 2:1 depending on their molecular size. In other words, for every ~2-4 molecules of Factor Xa they inhibit, they will inhibit 1 molecule of factor II.

Fondaparinux ONLY has factor Xa inhibition activity. Because it only consists of the pentasaccharide sequence, there is no factor II inhibitory activity.

Source: GIFER

Ok great! Based on just the couple of concepts above, you should now be able to answer all of these following case questions.

Case #1: A patient on your service is found to have right lower extremity swelling and redness. A doppler was performed and confirmed the presence of a DVT. The team decides to start unfractionated heparin as a drip to treat this new DVT. The next day you come in and the nurse comes up to you. They say that they have been titrating the heparin drip appropriately per the nomogram since yesterday but the aPTT (a lab that we use to monitor heparin’s anticoagulation effect) has not budged much and is still near baseline, despite the high heparin rate.

So let’s think this one through. The first thing I would always consider is: “is the heparin actually running?” and “is the IV line appropriately connected to the patient” and “did we sample the blood from the right location”?

Assuming all those are correct, and the patient is still on a whopping ~28 u/kg/hr of heparin – there’s most likely another cause.

An antithrombin deficiency.

Based on the mechanism of action we discussed about – without antithrombin – heparin cannot exert its effects.

You tell this to the team. The team then asks if we can start enoxaparin (a LWMH) or fondaparinux instead. You respond with:

HELLL NO. Because you know that no matter which heparinoid we use, all require antithrombin to work.

In order to fix this issue we can either:

- supplement the patient with antithrombin (eh not really done, very $$$$) OR

- switch to a parenteral (IV) anticoagulant that has a direct mechanism of action (aka doesn’t rely on something in the body like antithrombin to have its effects).

In this scenario, based on your *chefs kiss* knowledge of the mechanism of heparin, you recommend stopping UFH and switching to bivalirudin (a direct thrombin inhibitor, or DTI). The patient’s aPTTs start to come into therapeutic range.

Case #2: A patient comes in to your unit and reports having an allergy to pork products. She reports having a severe reaction when using heparin but remembered that one class of heparinoid anticoagulants worked well for her. Which heparinoid class is she talking about?

If you guessed fondaparinux you would be correct! Since fondaparinux is synthetically manufactured and not taken from porcine intestines (like UFH and LMWH), fondaparinux is an acceptable option for both religious or allergy restrictions against pork products.

Because fondaparinux is synthetic, it is also considered a reasonable option to use in patients with a history of heparin induced thrombocytopenia (HIT), unlike all the UFH and LMWH, which are contraindicated.

That’s it for today! Hopefully by understanding what these agents actually look like and how they work, you can have a better understanding of the nuances about different agents.

PS: Happy Valentine’s Day! I totally ruined the spirit of today’s holiday by having a heart failure discussion with my students bright and early this morning. Nothing screams anti-Valentine’s day like talking about a broken heart. 💔💔💔💔

Your style is unique compared to other people I have read stuff from. I appreciate you for posting when you have the opportunity, Guess I will just book mark this blog.

LikeLike

Way cool! Some extremely valid points! I appreciate you writing this write-up plus the rest of the site is also very good.

LikeLike