Hi guys! It’s been a while. Have been busy with work and life, and ya know, casually had a baby, who has since turned 1! Here’s my little lady on Halloween (she was Dumbo).

Anyway, today we are going to talk Transcatheter Aortic Valve Replacements, also known as TAVRs (pronounced TAHVER). TAVRs are one of the things that I geek out to my learners about, since they are truly an example of modern technology totally changing the landscape of medical care.

Just 1 or 2 decades ago, the only way we could replace a patient’s aortic valve was to cut them open, crack open their ribs, put ’em on bypass, and do a whole open heart cardiothoracic surgery. If you remember from our earlier talks on valvular disease, this posed quite a problem – especially since a good chunk of our patients who would need this operation tended to be old and at higher risk for complications with such a large surgery. But – then again – if we didn’t do a surgery, these patients would either develop heart failure and/or their HF would progress. It was kinda like a whole “between a rock and hard place” kind of situation.

Let’s talk a little history of how these modern marvels came into being.

History of TAVRs – a story that should remind you to never give up

The year was 1989. Big hair was slowly getting smaller as the 90s approached and a Danish cardiologist in his 30s named Dr. Henning Rud Andersen was attending an interventional conference in the US where the developer of the balloon-expandable stent was talking (but also isn’t it crazy that even cardiac stents are so fairly new in the grand scheme of medicine?). Coronary artery stents were all the rage and all of a sudden it hit Andersen – if we can deploy a stent in the coronary artery with a balloon, why can’t we use a balloon and build an expandable heart valve with a metal frame?

When he came back to Denmark, he shared his idea with some colleagues and professors, many were skeptical and called him crazy. But Anderson took a page out of Taylor Swift’s book and shook off all his haters and continued on his idea by himself, without any funding or industry support.

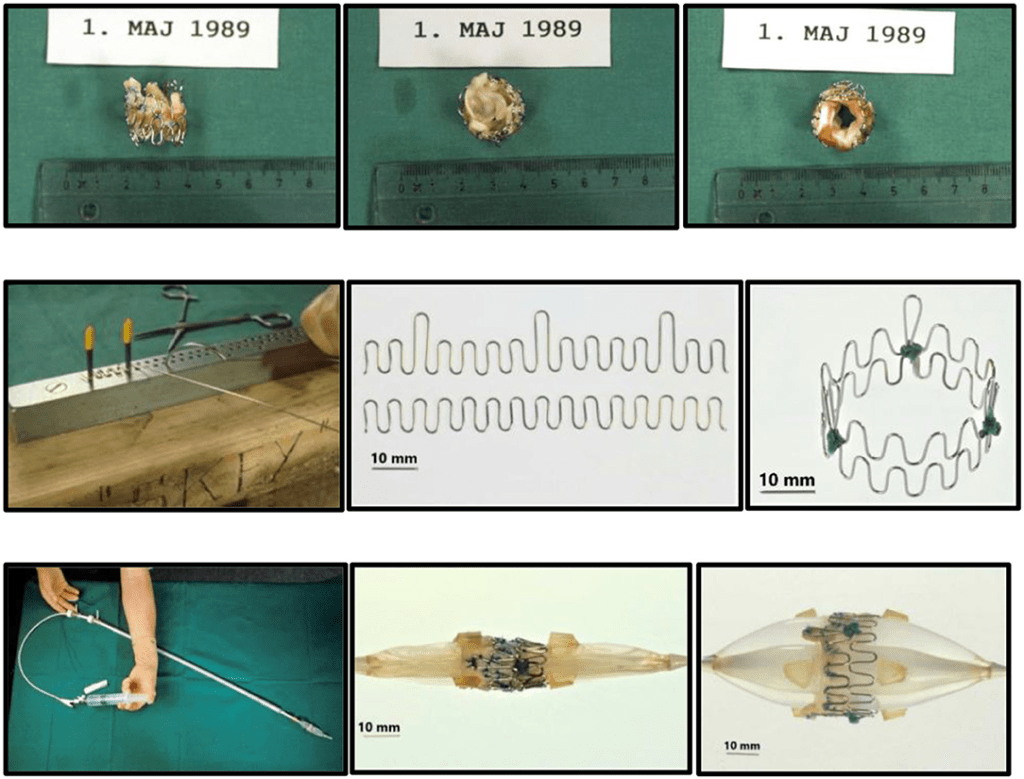

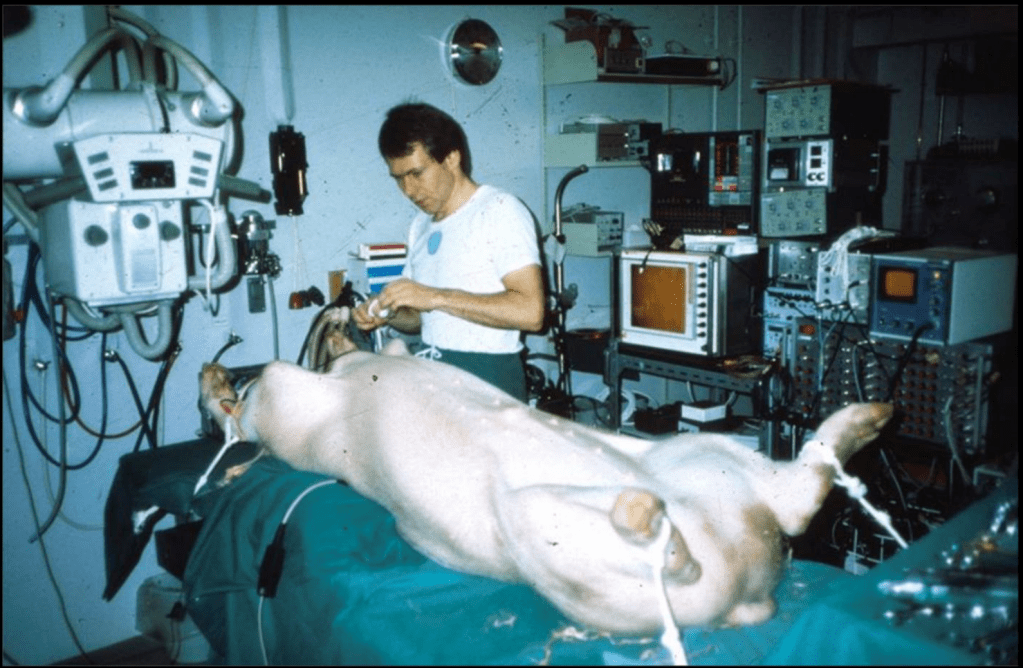

This guy quite literally MacGyvered a valve prototype – he went to local hardware stores and bought steel and iron wires to build his struts for his valve and soldered his first prototype together. It took a lot of trial and error – too thick, and the wires were too stiff to get good dilation by just a balloon, too thin and the wires failed to maintain structural integrity. Per Andersen himself everything was done by eye aka evaluation was done by “simple visual observation and gentle finger compression”. He also went to local slaughterhouses and bought pig hearts, carefully cut out the aortic valves, and mounted them in the stent. He had to re-use balloon catheters after being used in patients, which often did not fit and were too small for the aortic valve size of pigs, where he would refine the technique in (for reference, adult aortic annuli are like ~6 mm; pig’s are like 13mm!)

Just months after his initial idea, Andersen did his first-in-animal implantation in May of 1989 on an adult kg pig and it was a success. The other crazy thing was that in pigs, the femoral artery was too small to access (e.g. only 3-4 mm wide) and so he obtained access to the aortic valve by performing abdominal surgery and going through the ABDOMINAL AORTA. woof – so much for “minimally invasive”. Not surprisingly, in his initial days, sometimes the pigs would die even before implantation due to the extensive abdominal surgery.

Sometimes the balloons ruptured before fully inflated because they were makeshift quality . Sometimes he would implant them and the valve itself would block area of the aorta where the pig’s coronary arteries branched off (aka the coronary ostia). Sometimes the valve dislodged and broke off because the size was smaller than that of the pig’s aortic annulus (width where the aortic valve sits). Sometimes the whole thing would be pushed downstream and end up in the ascending aorta with blood flow. As Andersen said years later, he learned that “one size of pig does not fit all secondhand balloon catheters!”. One poor medical student even implanted the valve upside down (Andersen still mentions this years later – can you imagine being that poor unnamed med student who made a mistake and are still low key living in shame all these years later when he/she sees articles about it!?).

Another issue was that it was really hard to precisely implant/expand a valve in such a wild fast-moving area. Think about it – the aortic valve sits right where that left ventricle is squeezing out blood super, super strongly. To fix this issue in the early days, Andersen literally temporarily stopped all blood flow by inflating another balloon and placing it in the common pulmonary trunk. WILD.

But…more challenges.

In 1990, Andersen and his team submitted an abstract in hopes to present his poster on his initial work….and it was rejected.

That same year, he submitted a manuscript to a journal for publication for this ground-breaking work (submitted to JACC) – and…was rejected.

Then they tried again, and submitted to Circulation, another journal – who quite literally responded with “I do not see any possible use of it in patients with calcified aortic stenosis” (bet that reviewer is eating their words now). Suffice to say, their publication was once again rejected.

They finally submitted to a journal with a “extremely low impact factor” and were accepted; another paper was accepted in another little-known journal.

With these publications, Andersen finally got accepted to present at ESC, but only as a poster presentation. Needless to say, his team was bummed. Per Andersen it seemed that they “could not be published in major prestigious journals with high impact factors ort presented as oral presentations at international conference”.

Eventually, some other cardiologists and scientists heard of his work, and started replicating it in other animals like dogs, and eventually it was attempted on patients who were so high risk for surgery, no surgeon would touch them.

Fast forward through many decades of persevering in the face of opposition, likely imposter syndrome, and not listening to all the haters and….

Started from the bottom, now we’re here

The year was 2011. TAVR had since become more accepted, with the first in human completed in 2002, and its popularity slowly growing.

Andersen’s father is found to have severe, symptomatic aortic stenosis at the age of 86. Too old and frail for cardiothoracic surgery, his father QUITE LITERALLY UNDERWENT TAVR which saved his life.

Let me say that again.

Andersen’s work from over 20 years earlier saved his father’s life 22 years later. The procedure was a huge success and his father was walking the same day as the procedure and home a few days later. He lived for another 8 years without cardiac issues and died at the ripe age of 95. If Andersen had given up when times got tough years earlier, his father might have arguably died at the time.

This story lends credence to the idea of never giving up, silencing out your haters, and never letting imposter syndrome get to you. Let that sink in.

TAVR today

TAVR today is getting more and more popular, and is frequently performed. Luckily for us, the procedure is now minimally invasive, a far cry from the initial days of abdominal aortic access with Andersen’s pig friends.

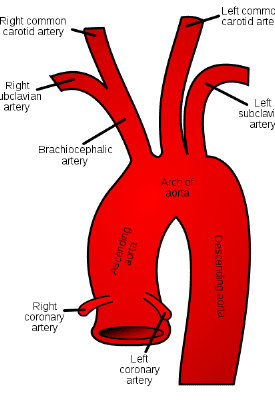

Access is usually accomplished through the femoral artery but other accesses such as subclavian is possible. The procedure is done by an interventional cardiologist (same people who put in stents but usually with some additional valve training) in the cath lab and is done percutaneously with a catheter.

The video above is a nice visual to show how implantation is done. The catheter in inserted in one of those large arteries, and goes against blood flow up, up the aorta, through the descending aorta until it reaches the site where the aorta valve sits. This is where deployment happens.

Thankfully for us, we don’t actually do any specific occlusion of arteries or veins to get blood flow cessation. However, it still is important to get minimal cardiac output as the interventionalist places the valve, since unlike some other procedures (like the MitraClip), this is a one shot thing. Once placed, you can’t reposition the valve and try again. Which means if it is misplaced, oftentimes the baton will be passed to the cardiothoracic surgeon to go in and fix the issue physically – which means an open heart surgery.

To help decrease cardiac output, we induce rapid ventricular pacing during implantation. Right before implantation, a pacing wire placed in the left ventricle will be turned on, and basically induce almost like a ventricular fibrillation vibe in that LV. In other words, we can make the LV stop contracting hard and reduce cardiac output for a few seconds as that valve in placed so it can be placed precisely.

Complications

Although TAVR is much better tolerated than an open-heart cardiothoracic surgery, it carries risks just like anything else. Let’s think through some of them together.

The first maybe more obvious thing has to do with the access itself. You’re entering a major artery, which is a high pressure system. While this is done pretty routinely these days, you still carry a risk of bleeding at the access site (albeit much less than what we see with open heart surgery). Procedure site bleeding, along with bleeding after the procedure due to the pharmacotherapy you have to take with it (we will talk about that next time) is really one of the biggest risks of TAVR. Patients also need systemic anticoagulation during the procedure so no clot forms on, or flecks off of the catheter. Other things that come with catheterization can also happen like risk of infection (especially when femoral access is obtained – we tend to have a lot of nastier bugs “down there” in that area) and rarely risks of things going awry with the procedure itself like misplacement of the valve or the catheter wire perforating something.

There is also a theoretical risk of occluding the coronary arteries, though this is very rare since the team carefully accounts for their anatomy (which is occasionally why some patients may not be good candidates for TAVR).

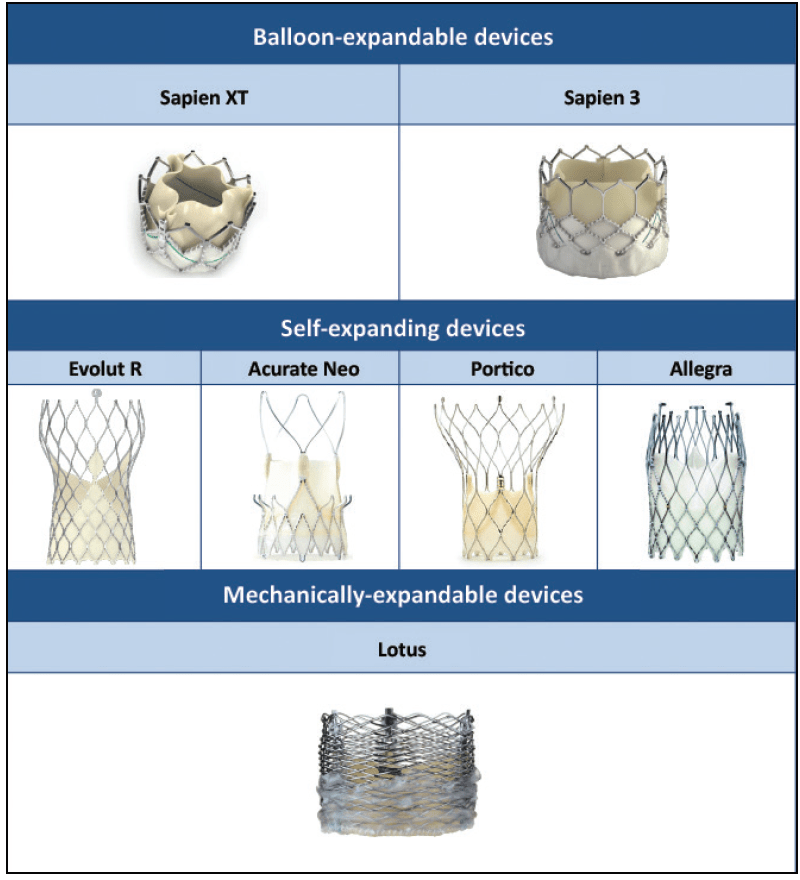

We also have quite a bunch of types of valves to now choose for to do this procedure with. Some are much shorter, meaning they may not interfere with the coronary arteries; others that tend to be longer, purposefully try to make their mechanical strut pattern wide so that, if needed, coronary access may still be possible in the future if needed.

The team will often do a coronary artery catheterization to check for any significant coronary artery disease in their initial evaluation for TAVR since once a TAVR is deployed, coronary access may be harder since one of the metal struts may make it hard to maneuver into that area. Better to clear a patient prior or perform necessary PCIs prior to make sure their coronaries won’t be a problem in the future once they’ve gotten their valve.

Besides bleeding, another complication of TAVR is valve thrombosis. Afterall, you are putting in this foreign tissue with metal strut object into your bloodstream, and we all know the coag cascade loves a foreign object to get itself worked up and activated. The risk is fairly low – compared with, let’s say a fresh coronary artery stent – but we will discuss this when we discuss medications in our next post.

Another more major complication of TAVR is stroke. If you noticed, not once in this whole post have I said we actually remove the pre-existing crusty valve that a patient had in there. When TAVRs are done, that old valve is simply pushed out of the way with the deployment of our new valve. As this valve is pushed out of the way and crumpled, it is very possible that flecks of the calcified tissue can break off – and once off, these pieces have a one-stop shot straight up to the brain and can cause an ischemic stroke, since the major arteries carrying blood to the brain are located soon after in the aorta.

To prevent this from happening, these fancy “embolic protection devices” have been created. These are basically fancy nets that filter and protect the major vessels that go to the brain and these are deployed during the TAVR procedure and then taken out .

From the interventionalists I’ve talked to, it is not uncommon at all to find some crud in these nets at the end of most TAVR procedures. Exhibits A and B below:

Despite these devices, strokes can still happen after these devices are removed, especially in those early days post TAVR implantation. Or, besides calcified material, it’s also possible that some clot can form as a result of the tissue damage in that area, and a clot can flick off and embolize and cause strokes. Besides strokes, technically any of those evil flecks above can cause any arterial embolism if blood flow carries them past those vessels that carry blood to the brain and further down the aorta.

Hope you enjoyed today’s TAVR background. It’s one of my favorite stories to tell, especially to learners. Next post we will focus on pharmacotherapy and what these patients need post-TAVR, including a little history of how these meds have evolved over time. Thanks for tuning in!

Congrats on the new baby!! Glad to have the blog back!

LikeLike